Read One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution Online

Authors: Nancy Stout

One Day in December: Celia Sánchez and the Cuban Revolution (53 page)

ALSO IN 1962

, Fidel reminded Celia that it was time to assume responsibility for the child they’d named Eugenia and baptized in the cave near Altos de Naranjo, whose father, Pastor Palomares, wanted them to raise her and give her an education. Celia wrote a letter to the grandparents. She waited and heard nothing, then sent three telegrams, and these, too, went unanswered. Fidel sent a man to get the child.

“I felt very proud,” Eugenia Palomares told me. “There was someone called El Morito who came on horseback. I came to Havana with a small box that held my three dresses and my only shoes.” Celia arranged to have a woman meet them in Providencia, and bring Eugenia to Havana.

“When I arrived it was night. Celia was waiting. I didn’t know her but my grandmother told me: when you get to Havana you’ll meet your godmother who is a very thin woman, and your godfather is tall with a beard. You should ask for their blessings.” Asking godparents for their blessings was a traditional courtesy in Cuba. “I said to Celia: Give me your blessing, Godmother,” Eugenia recalls. “I hugged and kissed her. She did answer me, but not like my grandparents, who said:

Santica mija

, God bless you. Celia presented me to Ernestina, the cook, very affectionately, and to some other people I think were guards. They looked at me with pity. After all these years, I now realize her reason: my body was weak and my spine was curved from carrying wood and pails of water for my grandparents. I was very thin, but my belly was bloated from parasites. My grandparents only knew about herbs.” On that first day, Eugenia felt that Celia had snubbed her greeting. This was followed by a sense of inferiority when she sensed how shocked they were at her appearance.

The next morning, she woke up feeling sad. “I missed my grandparents, their house, the mountains, everything. I had never seen electricity, a television, air conditioning, or a gas stove, since ours had been wood. Or seen floors. The floors in our house were of earth. Or walls. Ours had been made of planks and parts of the palm tree. Or a ceiling, since ours was made out of pieces of zinc and palm. I’d never heard this way of speaking, or known these kinds of people. All of it made me cry.” Ana Irma Escalona took charge of the situation. “She combed my hair and showed me how to wash, because I’d never seen a bathroom.”

ANA IRMA ESCALONA HAD COME

to Havana in hopes of getting a scholarship, and Celia had asked her to stay at Once. Ana Irma, who worked for Angela Llopiz and did some courier work for Celia during the days she was hiding in the underground, took charge of all the apartments: Celia’s public one, where everybody congregated around the kitchen and dining area, and Celia’s private apartment that contained her bedroom and office. Celia asked her to be Fidel’s housekeeper, too, taking care of the new apartment on the roof. Mainly, Ana Irma took care of his clothes, since he showed up every day to replace his uniform and put on a hand-laundered, carefully pressed one. These uniforms were hung

in large closets in a separate dressing room created for him in one of the back apartments on the first floor. Ernestina González, Celia’s cook, also became Fidel’s cook.

ON EUGENIA’S FIRST MORNING

at Once, as soon as she saw Celia, she ran and gave her a kiss. Again, she asked for “your blessing, Godmother,” and Celia seemed to consider this, but chose instead to remain silent. But she hugged Eugenia, and kissed her, and asked her how she’d slept. Miffed, “I didn’t answer her question,” Eugenia says. Then Ernestina served breakfast, which included bread and butter, new to the little girl’s palate; she was not consoled by food. Ernestina then handed her a glass of cold water from the refrigerator, which Eugenia set on the floor, in a corner, copying her grandmother, who used a glass of water as a talisman. Things improved later in the day when Celia presented her with a big doll. “It was my first toy. In the hills, dolls were made from rags.” And sent her shopping for new clothes.

When Fidel arrived, Eugenia was with Celia, Ana Irma, and Ernestina in the kitchen. He came in and Celia introduced them, “Look Fidel, this is Palomares’s little girl.” Fidel sat down, pulled her onto his lap and asked, “How are your folks?” and Eugenia told him they were well. “How are your studies?” She replied, “Well.” So far, two short answers. “Then he asked me if I knew how to cook. I answered yes, and he said, ‘Well, tell me, what do you know how to cook?’ I said, ‘Mostly I know how to roast coffee.’ Then and there, he asked me to tell him how I did this. I told him that my grandmother would stand me on a chair near the stove and I would move the coffee beans around inside the pot, and that it took a lot of time. When the beans got dark, and had a strong smell, we’d put in a little bit of brown sugar.”

Fidel encouraged her to tell him what else she was able to do, so Eugenia explained how she’d help her grandmother when a pig was slaughtered. “Two or three of us would go to the river to wash the intestines. We’d come back and my grandmother would make blood sausages and we would braid the small intestine. All this seemed to interest him, so he continued to ask questions, especially about the seasonings.”

On the following day, Celia sent her to see Dr. Álvarez Cambra, an orthopedist. Eugenia revealed, with his prompting, that she

always carried pails of water from a well to her grandmother’s house, walking on a very narrow path with a heavy pail in her right hand, and carried wood the same way. “I’d take wood to the river where my grandmother went to wash clothes twice a week.” One of Eugenia’s hips was higher than the other, which called for therapy. After that, Celia’s nurse, Migdalia Novo, picked Eugenia up at 5:30 every morning, and they’d go to the gym at an orthopedic hospital. At 7:00 they ate a packed breakfast, and Migdalia would take her to school and show up again to bring Eugenia home, to Celia, at the end of the school day. “Celia gave me a kiss every day when I came home from school. She’d ask what I’d learned that day.” But it was Fidel who could easily spend hours talking to her.

BY THE END OF 1963

, Celia had nearly finished setting up her own parallel security system. She had been moving her old friends from Pilón into houses around her building on Once as they became available since she didn’t fully trust state security. She was creating her own safety zone.

“Half of Pilón came to live on Once Street.

Gente de confiance

. Eventually, her Pilón friends lived on the street all the way from Paseo to 16th, or eight city blocks. You might say that she planted the street with people she could trust,” Celia’s nephew Sergio Sánchez told me, chuckling.

His parents had moved to Havana and occupied a house on 12th, but the back door opened onto the end of Once, and the kids in the family—Flávia’s, Silvia’s, Acacia’s, and Griselda’s children—often entered Celia’s house via Silvia’s, going in her front door and exiting out the back. They describe how Celia concentrated on landscaping in the ’60s, always having trees planted. She put in lots of fruit trees, choosing large ones, so people couldn’t see her building from the street. “There were three

nispero

[sapodilla] trees with small fruit, brown on the outside and light purple or red violet fruit. When they bloomed, Celia would put a net, a mosquito net, over them so the bats couldn’t eat the fruit. They were big trees. This created a stir, and a lot of comment in Vedado, since these trees came up to the first floor.” Raysa Bofill, Griselda’s granddaughter, recalls Celia’s garden, as do several of the children. There was a tangerine tree with lovely fruit that Celia wouldn’t let them pick because “they’re for Fidel.”

When I visited Berta Llópiz, we sat on her balcony and could see Celia’s building, but not clearly because the trees were in the way. Berta assured me that Celia planted trees of all kinds to camouflage the building, particularly from above, to keep it out of view of U.S. planes flying overhead. And since security guards block the street, Berta and I could not stroll over to inspect the building.

With Fidel living there, on a permanent but slightly ad hoc basis, state security moved into the two back apartments on the ground floor. Celia preferred her method to theirs, thought they called too much attention to the place, and in the first few years claimed everyone knew when Fidel was there from the number of cars outside. So she built a garage so Fidel could drive into the building—she did this by knocking down the next house and building an addition to the apartment building.

IN 1963, FIDEL STARTED TO PLAY

basketball again. In high school, he’d been the star of his team, so he started using the court at the Ranchos Boyeros arena every day. This large, circular-shaped facility is located on the highway to the airport, and Celia thought it was too dangerous for Fidel to go there, but carefully refrained from mentioning this; instead, she lauded his exercise. She asked a well-known architect, Joaquin Galvan, to design a multistoried gymnasium with a basketball court and a bowling alley, and the huge, poured-concrete building was constructed near Once. (Later, she had a swimming pool complex built, facing 12th Street.) But, in many ways, the gym was a great success. Raúl Corrales saw Celia nearly every day then, and says, “Evenings, he would work with her. Afterward, he would play basketball, or bowl. He began to use this ‘sports time’ to discuss things with people. She would say, ‘Come to my place tonight,’ and people knew that they would have an opportunity to speak with Fidel.” These appointments, surrounded by the camaraderie of sports, were casual and extended far into the night. It seems that everybody liked her solution.

In my lifetime, women in a similar position, that is, first Ladies, have redecorated rooms, but none to my knowledge have ordered major pieces of construction. But Cubans don’t see this as presumptuous. She was a hero, and her war record afforded her “the right,” as Cubans like to say, to make high-level decisions, particularly those that enhanced the safety of Fidel.

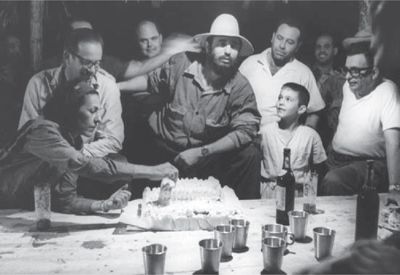

Celia organized a party to celebrate Fidel’s 37th birthday on August 13, 1963. While she cuts the cake, and the President of Cuba, Osvaldo Dorticos, watches from behind her, someone has just placed a straw hat on Fidel’s head. (

Courtesy of Oficina de Asuntos Históricos

)

CUBANS WERE NOW FIVE YEARS

into the Revolution. Concerned people (not to be confused with conservative people) still thought their leading couple should have gotten married. This sentiment is still voiced by people from Oriente Province who think of Celia as their hometown girl. They continue to be displeased with Fidel. Celia, to them, was straight out of an adventure story: they’ll tell you that they knew about her before they’d even heard of Fidel. She’d been their beauty queen, their Madonna (Sisters of Mary chairwoman), their benefactress (the King’s Day toys), Angel of Mercy (nurse in her father’s no-fee medical office), and when she turned into an outlaw (worked against Batista’s government and escaped arrest) and became their own “Most Wanted Person” (after the landing), even the least risk-taking citizens had loved her and hidden her in their houses. People of Oriente prayed for her, celebrated her survival, watched her become a war hero, saw her take her rightful place in Havana. They followed her on television, would see her in parades or taking part in conferences. Fidel is great, they told me, but what is the matter with the guy? She risked her life for him. He should have married her. To this day, they want to see the fairy tale come to its proper conclusion, and feel gypped at the outcome. In Oriente, it is the people who love

Celia. The unresolved relationship is still a bone of contention, one without resolution.

FLÁVIA TOLD ME THIS

: “There was

no amor

, like people say. It was a relationship that was neither romantic nor platonic.” Celia would brush off questions by saying that she and Fidel were “work comrades.”

No amor

is precisely the age-old recipe for good marriage. Affection and not romantic love is what it takes to make the long haul. If popular psychoanalysts, such as Ethel Spector Person or Stephen Mitchell, are right, romantic love, in most cultures, is considered to be too catalytic and confrontational for the day-in and day-out requirements of marriage. They write that society stays away from romantic love, this “act of the imagination” where the rules of engagement become inventive and passionate, set by only two people, the two that are involved (presumably blocking out all those other people, like in-laws, who want to be in on it). Yet both Person and Mitchell have found that cool and rational partnerships fall so far short of emotional expectations that, increasingly, people are willing to have a period of too much

amor

even if it usually doesn’t last forever. Or, as Mitchell writes, it doesn’t last forever because, out of fear of losing it, they essentially kill romance. Only the very brave and inventive make it last forever.

Brave and inventive—Fidel Castro and Celia Sánchez Manduley were that, and much more. I suspect they had exactly what it takes, and chose not to go public with it. They absolutely did not relinquish their loyalty to each other, or their day-to-day contact. They forged a bond to weather all storms. Maria Antonia Figueroa called it a life made up of “days of treason, days of deception, sometimes followed by days of glory and happiness.”