One Hundred and One Nights (9780316191913) (30 page)

Read One Hundred and One Nights (9780316191913) Online

Authors: Benjamin Buchholz

I PAUSE WHILE THE

cacophony catches up to me, while the spinning of my head, the last of the noxious, blaspheming whiskey, leaves me. I pause while I sit comfortably on Mahmoud’s three-legged chair, waiting for the convoy to approach along the northern road from Baghdad, hoping it arrives before Hussein and his mob.

I’VE FIGURED IT OUT.

I’ve come to a realization.

It might sound crazy, crazier than anything else I’ve said or done, but I think that I at last understand or can admit what has happened. I understand where Layla has gone, why she hasn’t visited me these last few days in the same fashion as she did during the first few weeks of our regular contact.

I’ve suspected that Layla isn’t real for a long time, but I didn’t know why.

I didn’t know. I don’t know. Not with any certainty.

But the anklet: it tells me something. At that first sight of Layla wearing the anklet, I should have known that she was nothing more than a ghost, a genie, a haunting, but I couldn’t admit to myself that the anklet was mine. I had strung together the bits of debris from my bombed house and had hidden the little loop of yarn under the counter of my shop, wrapped around the windowsill support beam. I had placed it there, stored it there, when first I opened the mobile-phone business. It was like a talisman for me, a touchstone during my first days of work in Safwan. I would reach under the counter, wrap my fingers around the anklet, and feel reassured, reminded of my purpose. I endured the miseries of starting life anew simply by remembering that collection of trinkets: bird bones, dollhouse keys, little bits of salvaged debris from the burned remains of my life in Baghdad, little bits of my daughter.

Layla isn’t real. I know that for certain.

She is a fiction, my fiction.

When I opened the box of gifts Ulayya rejected, here on the overpass, I saw again my Cubs hat, my heart-size rock, the clipped-off arm of the jack-in-the-box. These items confused me. But the anklet in the last box confused me even more. I was sure that I had seen her wearing it, this girl named Layla who haunted me in the market, this girl named Layla who reminds me of my daughter. I am sure that she wore it. But she couldn’t have been in possession of it before I met her. She must have been a dream. Likewise, she couldn’t have known the things she seems to have known. She couldn’t have guessed about America, about Chicago, about home. She is the last flaring, false as fox fire, of the spark that once filled my heart.

No more will I give credence to her seemingly solid apparition as it manifests itself before me. No more will I believe her when she whispers “I am here” to me, only to leave me clenching some blown-apart portion of her poor little figure. I will ignore this girl Layla and I will push forward into cold stark reality without her. I’ve constructed her from the best bits of my memory, the brightest moments from within my thirteen-year void, pieces of life that floated up to the surface and that I channeled into the dream of Layla’s presence around me here in Safwan. I will not carry pieces of my daughter around in my pockets anymore. Because I am burying my daughter, I know I also am burying Layla.

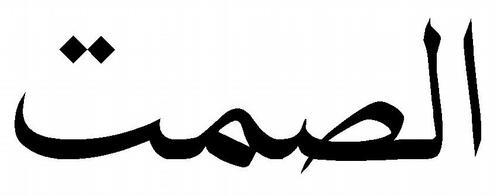

Am I more pitiable without her, without her as a crutch? When she is absent, I am staid, solemn, cold, and quiet, a man without humor, a man toward the end of his life who spends his remaining days counting convoys, watching a weak, heartbroken guard pace to and fro on a deserted highway overpass. Without these dreams and apparitions, I am drunkenly stupid, troubled, and not nearly as mystic or blessed as I have pretended to be. But with these hallucinations, I am only partially real. I’ve decided, just as I have given up the bottle, to give up my daughter’s ghost. I’ve decided to become real once more, no matter what pain it brings.

The realization of this helps, at least a little. The admission of this helps. It has taken me a long while to get here, but everything is clear to me now, not perfectly clear, but clear enough. Everything is quieter now, too.

I can endure these last moments without my hallucinations. I can, perhaps I must, complete my work in the real light of day.

My daughter is dead.

I’m only just a little bit crazy.

My daughter is dead and the admission proves, proves beyond doubt, that I have chased a phantom here in Safwan, a child as insubstantial as the wind.

Praise be to Allah, the All-Knowing, for His mysteries and for His majesty.

THIRTY-EIGHT SECONDS.

Abd al-Rahim arrives at my store just a moment too late.

I think it is he, first, who approaches, striding up the road from the center of town. I find it strange that he comes alone; Seyyed Abdullah would certainly task him with bringing Hussein and the whole gang of Hezbollah to the scene of the accident I am ready to create. I worry that Abd al-Rahim will surprise Mahmoud. I worry that he will be the one upon whom Mahmoud mistakenly dumps the bottle of acid, executing his well-deserved revenge. I had counted on Hussein to be the first to find me, the first to think of me hiding in my shop when I never came rushing, hair on fire and lungs filled with smoke, flushed like a hen from the bush, out one of the doors or windows of my burning house.

I should have thought that, as well trained as Abd al-Rahim is, he might be a step or two ahead of Hussein. I should have thought that he might reach my shop ahead of Hussein. I am about to stand, about to shout a warning to Abd al-Rahim, something like: “Don’t open the door!” But something prevents me. I do not shout. I hear the voice of the approaching man, sounding from the direction of my shack, but closer to town, still too distant for me to see him clearly.

I strain to hear the words the voice says, and at last I pick them out above the hundred other noises of the early-morning market. The man screams: “You raped her!”

Over and over the voice screams: “You raped her. You raped her! I beat the truth out of her. You took her honor, you bastard.”

I can’t discern the meaning of this. I think, Abd al-Rahim. But it isn’t Abd al-Rahim. I think, Hussein. But of course it isn’t Hussein. I hear the screaming of the voice grow louder as it approaches. I see the silhouette of the man in the dim morning light. It moves behind the frame of my shack, out of view. I hear the side door of my shack swing open, violently, smashing on its hinges against the opposite wall. I have run out of time to stand, to intervene. I hear a scream, then a gunshot, then a second gunshot—pistol fire, higher-pitched and quicker than the tearing recoil of a rifle.

After a moment, just long enough for me to let out my breath, I hear the pistol fall to the floor of my shack, making a dull thump on the wooden-plank flooring. The voice that had accused me of rape, the voice of Bashar, suddenly screams, continues screaming as a wild flailing and flapping, a tearing and cursing, fills my little store. Bashar runs from the shop, from the market, limping and brushing at his left leg where Mahmoud’s acid burns through his pants. He runs through the blue-tiled arch and away into Safwan.

I want to call to him. I want to run after him. I think of Mahmoud, who must be dying on the floor of the shack from the two pistol shots. I think of Bashar, fleeing, probably confused, certainly ashamed, certainly in terrible pain—the flesh of his leg eaten through and through. I decide to run after him. I decide I must help him, but as I stand, I see in the northern distance the convoy of prison buses finally approaching. Already it nears the off-ramp of the American bypass along the western edge of Safwan, not far, not far from me at all. The bus convoy won’t take the off-ramp. The buses are fated to continue toward me. Repeated observation confirms for me their route. They’ll maintain their speed and trajectory southeast toward Umm Qasr, toward the American prison camp at Bucca.

I sit once again on Mahmoud’s stool. My hands sweat. I wipe them on the front of my pin-striped, torn-open pant legs.

The lead vehicles of the convoy stream toward me. The noise of their engines overwhelms any last moaning, any calls for my help that Mahmoud might make as he dies. I reach into his tent and pick up his Kalashnikov with my bandaged right hand, the hand I bled to fill Ulayya’s bottle.

No need to stand.

No need to look nervous.

No need to be nervous.

Nothing out of place here.

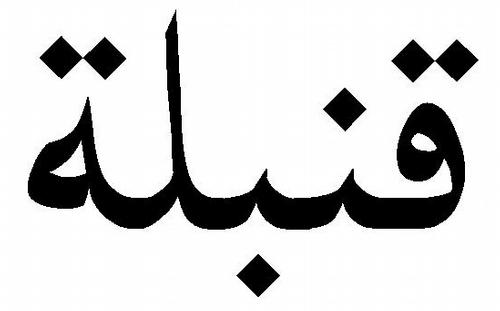

Quickly I glance at the bridge, where I have positioned the last of Ulayya’s presents and the infrared sensor beam through which the convoy must pass. The beam triggers the bomb. Most such bombs hit the passenger-side door. They are targeted to kill the commander of the vehicle, who sits in the passenger seat, operating the vehicle’s navigation equipment and radios. Maybe the bomb also kills the driver, passing first through the armored door and the body of the vehicle commander, ricocheting within, splintering, setting off boxes of ammunition stored inside the Humvee so that the whole vehicle ignites.

My bomb, though, I’ve timed to strike in a different way, not allowing that last tenth of a second to deliver the charge exactly against the door of a vehicle moving one hundred, maybe one hundred and twenty kilometers per hour. I want the charge to hit the front wheel of the vehicle. I want it to detonate early, to disable the chassis, nothing more. No need to kill Americans. I’m a friendly guard, dressed up in my engagement clothes. I’m a friendly guard, leaving presents along the roadway. Maybe I’m a little bigger than the guard who is normally on the bridge here—maybe I’m the uncle of that guard, older, taller, more confident in myself.

“My nephew is at a religious celebration,” I will say if they ask me, if they interrogate me.

Or perhaps, “My nephew is at an engagement party. A friend of his. I’m here in his place. What? Yes, of course I’ll be happy to keep an eye on the prison bus for you while you investigate the bomb that mistakenly struck the wheel of your buddy’s vehicle. Lucky for you that no one has been injured, no Patricks, no Davids. All things are as Allah wills…No, I didn’t see anyone place the bomb here on the bridge. I was paid to look the other way. We’re all paid to look the other way. No need to get involved in someone else’s war.”

The convoy speeds toward me.

Not much time remains.

I’d like to think that Abd al-Rahim arrives only after he hears the blast from the bomb, but that isn’t the way it happens. He arrives with the mob. He is too late to help me but he is just in time to execute his master’s true orders. He has brought Hussein. He has implicated Hussein. He has fulfilled his mission.

Together, he and Hussein open the door to my shack. They hope to find me but instead they find Mahmoud. Hussein rushes into the shack to prod at Mahmoud’s slumped little body while Abd al-Rahim, more savvy by far, looks up at the place where I sit on Mahmoud’s stool. He looks at me but he looks past me, too. He looks past me into the road, where the convoy cruises forward.

His mouth forms the word

No!

I follow his gaze.

He looks at Layla.

She stands there, there in the middle of the road. She stands with both hands open before her and her bare feet planted wide. She signals for the convoy to stop. She warns them. She waves her arms. She jumps up and down and does everything she can to make them stop, even putting her body between the convoy and the bomb. But it is too late.

I don’t believe in her.

I’ve decided she isn’t real.

It is impossible for her to be standing there with her hands outstretched and her teeth clenched and her eyes fixed forward on the grille of the onrushing Humvee. It is impossible: what I see of her is a mirage, nothing more. If I blink, she will be gone. If I concentrate more precisely on reality—on sunlight above, shadows below, the speeding vehicles, the heated sticky tar on the pavement, the trash blowing across the desert in the dry wind, the plan, my plan, my Greater Purpose—if I concentrate on reality, Layla will be gone. She is a figment of my imagination, my regret, my sadness. She is my dead daughter come back to haunt me or to bring my soul some semblance of life and laughter. She isn’t real. I signed no adoption papers for her. What was I signing in those moments of swimming, sharklike interrogation?

The convoy doesn’t strike her. It can’t strike her.

She isn’t real.

I don’t believe in her.

I don’t hear her body wetly collapse against the front bumper of the Humvee. The noise I hear, the gentle thump, the screech of the Humvee’s wheels, I must be creating in my torn-apart mind. The part of her that I see with my own eyes—as it turns, in a blink of infinitesimal time, from living thing to bloody dust—is a trick. Perhaps I hesitate, I dwell on Layla, because I am afraid of this moment of reckoning, afraid of the pledge I have sworn to myself to take my brother’s life. Perhaps, in this moment of heightened awareness, my mind replays and recasts the memories of a lifetime of pain and bloodshed and aloneness so that I am fooled into thinking that I see the body of a child standing in the road to block a two-ton Humvee.

Layla isn’t real. She can’t stop a convoy. She might dance like Britney Spears, but that isn’t real. It’s movie magic. It’s laser lights and light shows and liposuction. Britney Spears doesn’t exist any more truly than the tongue of the blind boy in front of the mosque. Abd al-Rahim has joined Hezbollah at his uncle’s command. And Layla isn’t real.

The first vehicle, that lead Humvee, swerves after it hits the apparition of her. It veers sharply to the right and smashes into the railing at the exact spot where I positioned the bird-bone anklet and the infrared laser. The vehicle cuts diagonally across the beam. The bomb explodes. The front end of the Humvee plants itself into the railing of the bridge. The back end jacks up like a bucking horse as the bomb blast lifts it over its pinioned front.

The Humvee vaults the railing, hurdles upside down over the roadway embankment. The gunner in the turret comes free of his harness. He tumbles with the vehicle. The objects, the huge Humvee and the body of the gunner, are like a falcon and a sparrow in an aerial maneuver, the sparrow doomed, clumsy, beating its wings against uncaring air. The Humvee falls to earth and drives a long ditch through the center of the tents and shacks that comprise the stores in the southwest leaf of the cloverleaf interchange. It skids across the ground and up onto the roadway that passes under the bridge, coming finally to rest just where I chose to locate my mobile-phone shop, the place Sheikh Seyyed Abdullah and I together chose because of its excellent view of the highway.

The Humvee teeters. Metal scrapes against asphalt and whines as it compresses from the heat of the friction and of the blast. Near it, Hussein emerges from the door of my shop. He stands motionless and erect as a bird that has caught its prey. When the Humvee stops rocking and screeching, I see him bend down to the pavement. For a long second he squats and then he picks up an object that has rolled to a stop at his feet. He lifts it by the hair and holds it in front of him. Blood drools down his forearms.

Layla?

Layla isn’t real.

She is a figment of my imagination.

I look for Abd al-Rahim, who had stood in just the same spot where Hussein now holds a little girl’s head. I look for Abd al-Rahim and find him, oddly, as if he has dodged the falling giant missile of the wrecked Humvee, juking and jiving and slipping past certain death, running bravely forward toward me, running bravely forward past me, running bravely forward into the middle of the roadway, where smoke boils from the bomb crater and draws a veil around the scene like a curtain falling at the end of a theater show. Abd al-Rahim moves offstage. The smoke wraps around him. I wait for a moment, expecting to see him emerge, maybe doing the backstroke, maybe now finally feeling confident enough to swim in the deep end of my dark Lake Michigan nightmare.

Maybe he isn’t real, either.

Maybe he will dissolve into goldfish.

Maybe he will plug his nose, dive, and come up from the mucky depths of the lake with a handful of Layla. Maybe he will return for a curtain call, for a tossed bouquet, for headlines in the daily gossip column and comments on his nice shoes.

The buses in the convoy can’t turn as sharply as the Humvee. They are spared the fate of vaulting over the railing of the overpass. They continue down the highway for a short distance through the crater of my exploded bomb, each of them veering to the edge of the road, magically avoiding the place where Abd al-Rahim’s imaginary body kneels over the imaginary body of dead Layla. I see them, Abd al-Rahim and Layla, wafting in and out of the broken bank of clouds. They are nothing more than two apparitions in a passing illusion.

They are unreal.

I do not believe in them.

The buses come to rest. They skid to a halt. The nearest of them is only three or four meters from the place where I wait on Mahmoud’s stool.

The deafening explosion rings in my ears. Everything except the most urgent of movements fades from my mind. I begin, aloud, to count.

“Thirty-eight, thirty-seven, thirty-six…” Whether I run toward the place where I think Layla’s imaginary flattened body lies, the place where imaginary Abd al-Rahim kneels, or whether I merely run toward the first of the buses, I do not know. It is one and the same thing.

“Thirty-five, thirty-four, thirty-three…” Whether I board the buses in an orderly fashion, each in turn, unobserved by the panicked and scattering security guards, who tumble, coughing and dizzy, into the roadway, or whether I run from place to place, half mad, I do not know. It is one and the same thing.