One Was Stubbron (4 page)

Sunlight!

And there it came again, that pleasant, golden beam.

But as soon as the sunlight came, the meadow vanished!

How uncertain all this was! Was it possible that I could create but not enduringly? That I could create and maintain only one object at a time? Did these things depend wholly upon my ability to concentrate upon them?

And even while I pondered the question, the sunlight faded before the mist and I was again surrounded by the clammy grayness. But for all my disappointment, I had established one thing: that I could bring things into being even if I could not maintain them.

Certainly there must be some solution to this sort of thing. If I gave it enough thought, perhaps I could manage a way to trap sunlight and meadows into reality.

I sat down upon my solidity and pursed my lips and stroked my chin. Try as I might I could not remember if Tribbon had had anything to say upon the subject of concentration.

I thumbed hopefully through the index, but the only reference close to it was “Concentration Camps: New York, San Francisco, Washington.” I stared into the mist a while and when I looked back at the book, it was gone. Oh, well, I thought, I would rather have some Old Space Ranger anyway.

I drank it off.

And it made me hungry.

So I ate the steak.

Feeling better, I again got restless. I could not sit around on an imagined solidity for all eternity. I could call down the sunlight at will, but I couldn't keep it there, and so I gave over. And then it occurred to me that the reason I thought I was standing upon something was because I had always stood upon something and was so used to the idea that I could not shake it.

And the instant it became an “idea” only, I fell. And I became scared. And I landed.

If I could only talk this over with someone, I sighed. But I was careful not to think I saw anyone, for people did not seem to like being hauled back from wherever they had gone. Certainly somewhere in all this there must be at least one other man. To think that I was the only one was conceit of the most outrageous kind. Somewhere there was somebody. And if he and I could just get together then he might know enough and I might know enough to put some semblance of a world together and keep it together.

Again I wanderedâand flounderedâand fell when I thought about my solidityâand landedâand pawed through this endless mist.

Once or twice I thought I saw people. But I could not be sure, for I was careful not to think they

were

people. And when I had spent a timeless space in stumbling about I forgot my caution and, seeing a misty thing which looked like a man, thought he

was

a man.

Very briefly he assumed a shape. It was nebulous and distorted as though I looked at him through a drinking glass just emptied of milk.

“Stop it!” he cried in a thin voice. “By what right have you dragged me back? Vanish and be saved!”

And he vanished.

From somewhere came caroling voices and an ineffably sweet harmony which I could not associate with any instruments I had ever heard. For an instant there came over me an exquisite longing to forget myself and my misery and join that chorus. But then I remembered Flerry and George Smiley and, doggedly, I went on with my search. Half an eternity, it seemed, of toiling search.

It took me a long while to discover that other one. A long while. I felt I had swum through a light-year of mist, had fallen through the bottom of the Universe and had scrambled skyward to the sun itself. But I found him.

He was a definite shape before I had any chance to think of him, and when I thought him not there he still was there.

I had found him!

He was above me perhaps fifty feet and he seemed to be sitting on air and dangling his feet over the edge. Great

gouts

of mist rolled between us, blotting us from one another's sight. But each time the mist cleared, there we were again. I could not contain myself for joy and he seemed to feel much the same way, for he waved his arms down at me and beckoned me up. I beckoned him to come down. We must have been farther apart than it seemed to our eyes, for he could not hear me nor I him.

He was evidently frightened to let go of his perch in air and so I had to take the initiative. I looked along the way from me to him and thought hard about a stair. And step by step the stair appeared. I ran up it, shouting at him the while, but, in my enthusiasm, I forgot the stair and it vanished.

I landed as soon as I was frightened of earth's impact and again built the stair. This time I looked at the steps as I went up and this time I arrived.

He was a diminutive fellow with a face which attested to a belligerent turn of mind. And his first greeting to me was, “Did you do all this?”

“No. George Smiley did it.”

“Who?”

“George Smiley.”

“Must have been an Earthman. I am from Carvon myself.”

“Never heard of that,” I said.

“Well, it

was

a nice place. I was researching on the regime of Vaso on Wwhmanin and all of a sudden my book vanished and here I was. And here I am.”

“Here we both are,” I said. “I've been looking all over for you. I need help. Did you see those stairs I just built?”

“Yes, but they're gone now. It wasn't such a good job.”

“Well, I've discovered that all we have to do is think of something real hard and then it will come about. And if we can remember itâ”

“If we can remember it. I've been trying to concentrate on a ham sandwich for a day and a half, but I keep forgetting it before I can eat it. Woops. There it goes again.”

“Now look,” I said. “I'll think about it, too.”

“No, let's get something to sit on first. I don't know what's under me and I don'tâ”

“Don't say that!” said I, barely saving him from falling. “All right, we'll think of a table. There! There's a table. Now you keep thinking about that table while I get a couple of chairsâ”

He shut his eyes and kept a grip on the table. I shut mine and imagined us sitting on chairs. And then there we were, sitting on chairsâ

“It's gone!” he said. And sure enough, the table was gone again. We had thought too hard about chairs. Finally we managed to feel natural and remember chairs and think of the table, too, and so, with some relief, we alternated thinking about things until we had something to eat and drink. But the trouble was that each time we would take a bite of something we would forget about the table and the food would plummet out of sight.

Somehow we filled up and then, looking thoughtful, he said, “You know, if we could just get practiced enough to think about all sorts of things, you and I, we could build the world back just about the way we want it. But the first thing we've got to do is to put the sun in the sky. I'm sick of this murk!”

“All right,” said I, “I'll think about the sun.”

And the sun shone brightly down. I must have been fairly well in practice, for I kept on talking and kept the sun up there at the same time.

“Now you think of Earth,” I said.

He thought about Earth and a sort of uneasy motion was set up under us and flashy bits of scenery popped into view and vanished and popped up again. Chinese tombs and a far-off domed city and a ferryboat on a lake all appeared and disappeared.

“It's not much use,” he said. “It just can't be done all at once. Let's imagine one town and then, when we get used to that and believe in it, we'll imagine the fields around itâ”

“All right. But we really ought to imagine something to build the town on. A great globe in the sky, twenty-five thousand miles in circumferenceâ”

“Let's be different,” he said suddenly. “As long as you and I can do this all by ourselves, we'll just put this together on some new principles. There's no use copying what we've already had. Now how about living inside the earthâ” He stopped in awe. “Why, weâ”

I cried, “Why ⦠why, we'reâ”

“Yes,” he said, “yes, we'reâ”

O

h, no, gentlemen,” said a silkily sardonic voice. And we both whipped around to find George Smiley standing there in his flashtex cape. “If there is anything to be built, then I shall build it. You two are the most stubborn of all, but you've agreed with each other. And now you can agree with me.

“I worked for years to sell the world the idea of nonexistence. And if anyone intends to build a world then it shall be me. Who put that sun in my sky?” And he waved his hand toward it and the sun went out.

“We've got a perfect right,” said my friend.

“No, you have not,” grinned George Smiley. “I faded all things into nothingness, even Time, for myself. And because I made the whole world believe and all the Universe, then the Universe is mine. And I shall build.”

“Why, you're trying to set yourself up asâ”

“Yes,” said George Smiley to my friend. “Yes, indeed.”

“We have just as much right!” howled my friend.

“I shall then give you half of it,” said George Smiley. “The lower, hotter half. I shall create a world for you alone to rule.”

“No!” protested my friend.

“Yes,” said George Smiley. “It's a quaint idea I got out of an old book. Now begone, both of you!”

And suddenly we were falling again. But this time no matter how much ground I thought about, no ground was there to stay me. My friend was soon separated from me and he did not see the water which suddenly spread below me. I know he did not, for he was still falling when last I saw him.

As for myself, I climbed out on a muddy bank of the Seine and wrung the water out of my clothes.

The United States Marines didn't even ask me any questions when they locked me in their jail as a possible enemy airman.

And I didn't volunteer any answers.

I was too glad not to have to think about that bunk before I stretched out upon it.

George Smiley can have the Universe for all I'll ever care.

A Can of Vacuum

A Can of Vacuum

B

IGBY

O

WEN

P

ETTIGREW

reported, one fine August day, to the Nineteenth Project, Experimental Forces of the Universe, United Galaxies Navy, and was apparently oblivious of the fact that ensigns, newly commissioned out of the civilian UIT and utterly ignorant of military matters, were not likely to overwhelm anyone with the magnificence of their presence.

The adjutant took the orders carelessly and as carelessly said his routine speech: “Space Admiral Banning is busy but it will count as a call if you leave your card, Mr. Pettigrew.”

Bigby Owen Pettigrew chewed for a while on a toothpick and then said: “It's all right. I'll wait. I got lots of time.”

The office yeoman stared and then carefully restrained his mirth. The adjutant looked carefully at Pettigrew. There was a lot of Pettigrew to look upon and the innocent-appearing mass of it grinned a friendly grin.

The adjutant leaned back. The Universal Institute of Technology was doubtlessly a fine school so far as civilian schools went and it indubitably turned out very good recruits for the science corps. But this wasn't the first time that the adjutant had wished that a course in naval courtesy and law could be included there. The practical-joking Nineteenth would probably take this boy apart, button by stripe and cell by hair. Obviously Pettigrew really thought an ensign could call on a space admiral just like that.

“Perhaps,” said the adjutant, “you have some important recommendations to make concerning the way he's running the project.”

Pettigrew shook his head solemnly, all sarcasm lost upon him. “No. Just like to get the lay of the land, kind of.”

“Are you sure,” said the adjutant, “that you haven't some brilliant new theory you'd like to explain to him? Perhaps a new hypothesis for nebula testing?”

With a calm shake of his head, Pettigrew said, “Shucks, no. I'm away behind on my lab work.”

The yeoman at the side desk was beginning to turn deep indigo with strangling mirth and managed, only at the last instant, to divert guffaws into a series of violent sneezes.

“You got a cold?” said Pettigrew.

The poor yeoman floundered out, made the inside of Number Four hangar and there was found some ten minutes later, in a state of aching exhaustion, by several solicitous mates who thought he had been having a fit. He tried for some time to communicate the cause of all this. But his mates did not laugh. They looked pityingly at him.

“Asteroid fever,” said one.

“Probably got a columbar throngustu, poor fellow.”

“Looks more like haliciticosis,” said a third, vainly trying to feel the yeoman's pulse.

“All right,” said the yeoman. “All right. You're a flock of horse-faced ghouls. You wouldn't believe your mother if she said she was married! Doubt it! But he's here, I tell you. And that's what he did. And you mark my words, give that guy ten days on this station and none of you will ever be the same again.”

The yeoman spoke louder and truer than he knew.

Carpdyke, the sad and suffering project assignment officer, who felt naked when he went to dinner without a couple of exploding cigars and a dematerializing pork chop, leaned casually up against the hangar door. The enlisted men had not seen him and they jumped. When they saw it was Carpdyke, they jumped again, further.

“What,” said Carpdyke, “did you say this young gentleman's name was?”

“Pettigrew,” said the yeoman, very nervous.

“Hmmm,” said Carpdyke. “Well, men, I'm sure you have work to do.” He was gloomy now, the way he always got just before he indulged his humor.

The group disappeared. Carpdyke went sadly back to his office and sat there for a long, long time. He might have been studying the assignment chart. It reached twelve feet up and eighteen feet across and was a three-dimensional painting of two million light-years of Universe. Here and there colored tacks marked the last known whereabouts of scout ships which were possibly going about their duties collecting invaluable fuel data and possibly not.

Carpdyke grew sadder and sadder until he looked like a bloodhound. His chief raymaster's mate chanced to look up, saw it and very, very nervously looked down. Just what was coming, the chief knew not. He hoped it wasn't coming to him. Carpdyke had been known to stoop so low as to rig a bridegroom's quarters with lingerie the morning of the wedding. He had even installed Limburger cheese in a spaceship's air supply. And onceâwell, the chief just sat and shuddered to recall it.

The door opened casually and Bigby Owen Pettigrew, garbed newly in a project-blister-suit-less-mask, the fashion there on lonely Dauphiom where beards grew in indirect proportion to the number of women, entered under the cloud of innocence.

The chief looked at Carpdyke, at Pettigrew and then at Carpdyke again. The assignment officer was growing so sad that a tear trembled on one lid. The chief stopped breathing but then when no guardian angel snatched Pettigrew away from there, the chief started again. No reason to suffocate.

“Hello,” said Pettigrew cheerfully.

“You're new here, aren't you?” mourned Carpdyke.

“I just graduated from the UIT,” said Pettigrew. “My name's Bigby. What's yours?”

“I'm Scout Commander Carpdyke, Bigby. We always like to see our new boys happy with the place. You like your hangars?”

“Oh, sure.”

“You found the transportation from the Intergalaxy comfortable and prompt?”

“Sure, sure.”

“And your room? It has a lovely view?”

“Well, now,” said Pettigrew thoughtfully, “I don't think I noticed. But don't you bother yourself, Commander. It suits me. I don't want much.”

The chief was beginning to have trouble swallowing. He went to the water cooler.

“Well, now,” said Carpdyke, looking very, very mournful, “I am happy to hear that. But you're sure you wouldn't want me to change quarters with you?”

“Change? Shucks, Commander, that's awful nice of you butâwell, no. My quarters suit me fine and no doubt you're used to yours.”

The chief sprayed water over the assignment map, dived straight out the door and kept going. A ululation of indescribable pitch faded away as he grew small across the rocket field.

“Did he get sick or something?” asked Pettigrew.

“A bit touched, poor man,” said Carpdyke. “Ninety missions to Nebula M-1894.”

“Poor fellow,” said Pettigrew. But he braced up under it. “Now, then, Commander, is there anything you want me to solve or fix up? Anything you're stuck on or

deep-ended

with? They put me through the whole ten years and I sure want to do well by the service.” He burnished a bit at the single jag of lightning on his lapel which made him an ensign, science corps, experimental.

“How were things at base? You left Universal Admiral Collingsby well, I presume.”

“Sure, sure,” said Pettigrew. “Read me my oath himself.”

“You and ten thousand other plebes by visograph,” muttered Carpdyke.

“Beg pardon?”

“Nothing. Nothing. I was just wondering where we could best use your services, Pettigrew. We have to be careful. Don't want to waste any talent, you know.”

“Sure not! I bet you have an awful time keeping up with problems, huh?” Vivid excitement manifested itself on Pettigrew's homely face for the first time.

“There,” said Carpdyke, “you have struck it. Keeping up. Keeping up. Ah, the weariness of it. Pettigrew, I'll wager you have no real concept of what we're up against here at Nineteen. Mankind fairly hangs on our reports, sir.”

“I'll bet they do,” said Pettigrew with enthusiasm.

“Here we are,” said Carpdyke, “located in the exact hub of the Universe; located for a purpose, Pettigrew. A Purpose! Every exploding star must be investigated at once. Every new shape of a nebula must be skirted and charted. Every dark cloud must be searched for harmful material. Pettigrew, the emanations of all the Universe depend upon us. Upon us, Pettigrew.” And here he heaved a doleful sigh. “Ah, the weariness of it, the weariness.”

“Sure now, Commander. Don't take it hard. I mean to help out all I can. Just you tell me what you want doneâ”

Carpdyke rose and convulsively gripped the ensign's hand. “You mean it, Pettigrew? You mean it truly? Magnificent! Absolutely magnificent!”

“Just you tell me,” said Pettigrew, “and I'll do my best!”

Carpdyke's exultation gradually faded and he sank back. He slumped and then shook his head. “No, you wouldn't do that. I couldn't ask you to do that.”

“Tell me,” begged Pettigrew.

“Pettigrew,” said Carpdyke at last, “I have to confess. There is a problem. I hate to ask. It's so difficultâ”

“Tell me!” cried Pettigrew.

Carpdyke finally let himself be roused. Very, very sadly he said: “Pettigrew, it's the rudey rays.”

“Just you ⦠the what?”

“Rudey rays. Rudey rays! You've heard of them certainly.”

“Well, now, Commander ⦠I ⦠uh ⦠rudey rays?”

“Pettigrew, how long were you at UIT?” And Carpdyke put deep suspicion into it.

“Why, ten years, Commander. Butâ Rudey rays. Gosh, I didn't never hear of anything like them.”

“Pettigrew,” said Carpdyke sternly, “rudey rays might well be the foundation of a new civilization. They emanate. They expand. They drive. But they can't be captured, Pettigrew. They can't be captured.”

“Well, whatâ?”

“A rudey ray,” said Carpdyke, “is an indefinite particular source of inherent and predynamic energy, inescapably linked to the formation of new stars. Why, Pettigrew, it is supposed that the whole Universe might have been created from the explosion of just one atom made of rudey rays!”

“Gosh. I thoughtâ”

“You thought!” cried Carpdyke. “Ah, these professors! They pour ancient, moldy and outmoded data into the hapless heads of our poor, defenseless young and then send them outâ”

“Oh, I believe you,” said Pettigrew. “It's just kind of sudden. A new theory, like.”

“Of course,” said Carpdyke, sadly but gently. “I knew you would understand. This matter is top secret. Nay, it is

bond

top secret. Pettigrew, if we had just one quart of rudey raysâ”

“One what?”

“One quart!”

Pettigrew nodded numbly. “That's what I thought you said.”

“Pettigrew, with just one quart of rudey rays we could run the United Galactic Navy for a million years at full speed. All five million ships of them. We could run the dynamos of all our systems for ten thousand years without stopping. Andâ”

Pettigrew was wide-eyed. “Yes?”

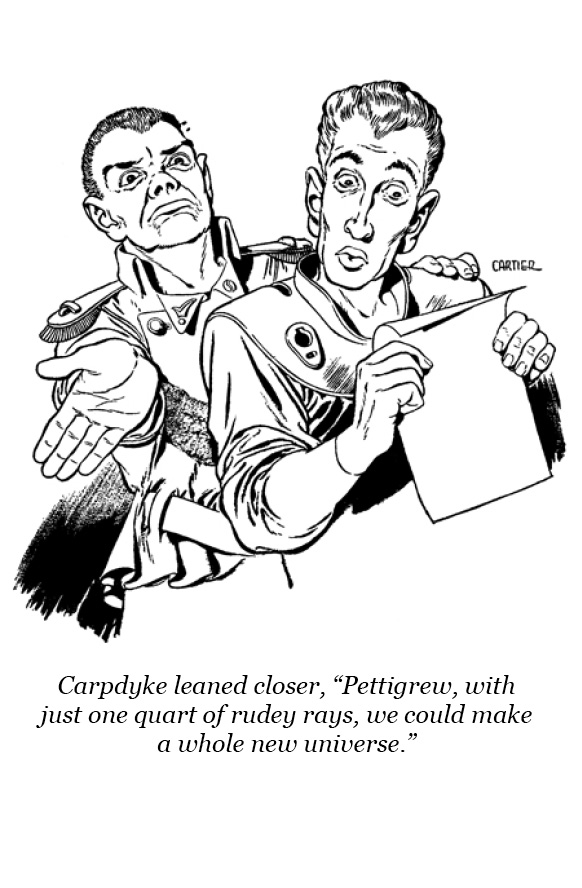

Carpdyke leaned closer, “Pettigrew, with just one quart of rudey rays, we could make a whole new universe.”

Pettigrew fanned himself uncertainly.

“Good!” said Carpdyke. “I'll give you your orders.” And before another word could be spoken he scrawled across a full page of the order blank:

TO ALL ACTIVITIES:

Ensign Bigby O. Pettigrew, pursuant to verbal orders this date to the effect that he is to locate, isolate and can one quart of rudey rays, is hereby authorized to draw necessary equipment on the recommendation of supply and laboratory commands.

Carpdyke

With a flourish he gave it over. And with a hearty handshake and a huge smite upon the back, Carpdyke propelled the ensign to the door. Pettigrew was thrust out and the wind fluttered in the sheet he held. He looked at it, frowned a little and then, squaring his shoulders manfully, strode purposefully upon his way.

Behind him Carpdyke stood for a little while, devils flickering in his eyes and something like a smile on his mournful mouth. Then he sat down.

“The first thing supply will send him for is a can of vacuum,” said Carpdyke. “I figure that should take him a couple of days. Then lab will wantâ” But he shook off these pleasures and looked moodily at his assignment blanks.

He'd have to have something new in three or four days. Pettigrew ought to be good for a solid month before he began to wise.

“Sir,” said the chief raymaster's mate, “dispatches from base.” He looked at them. “All routine.”

“I'm busy,” said Carpdyke, throwing them into the basket. He settled himself down to compound and compute the next mission of the luckless Pettigrew. “âNow, then, Commander,'” he mimicked, “âis there anything you want me to solve or fix up?'” He nearly chuckled. “Ah, Pettigrew, Pettigrew ⦔ He grew mournful again and the chief looked very, very uncomfortable as time wore on.

“Sir,” ventured the chief, “that top dispatch says a new batch of officers is being ordered in here. About fifteen ensigns, a couple of commanders and one captain, Congreve, to take over as exec. That's the Congreve that was cited for his work on new fuels. He'll probably make this place hot. Iâ”