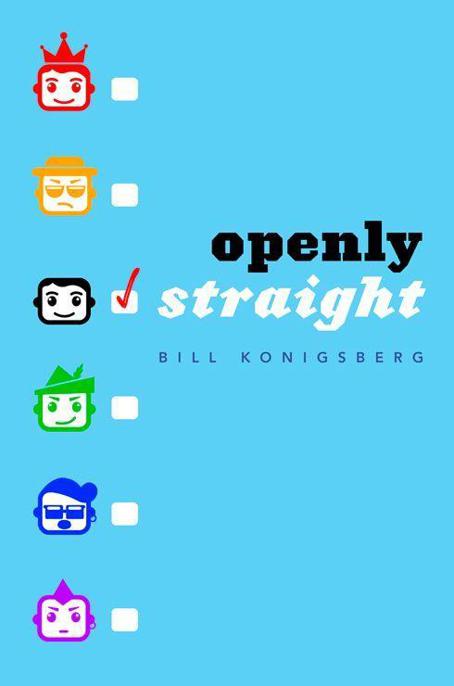

Openly Straight

Authors: Bill Konigsberg

For Chuck Cahoy, always.

If

it were up to my dad, my entire life would be on video.

Anything I do, he grabs his phone. “Opal,” he’ll yell to my mother. “Rafe is eating corn flakes. We gotta get this on film.”

He calls it film, like instead of an iPhone, he has an entire movie crew there, filming me.

So when he pulled his Saturn Vue hybrid up to a hulking building with a stone façade and I leapt out of the car to examine my new home for the first time, I wasn’t shocked that he went straight for his cell.

“Act like you’re arriving home after three years overseas in the army,” he said, his left eye hidden behind the phone. “Do some cartwheels.”

“I don’t think soldiers do cartwheels,” I said. “And no.”

“It was worth a shot,” he said.

The thing about it is nobody ever watches these videos. I have seen him record literally weeks’ worth of video, and I’ve never, ever seen him watch any of it, or put any of it on “the Face Place,” as he calls it, which he is always threatening to do.

“I’m going to throw that thing if you don’t put it away,” I said. “Seriously. Enough.”

He removed the phone from in front of his eye and gave me a hurt look, as he stood there in his Birkenstocks, his knobby knees glistening in the sun. “You would not throw my child.”

“Dad. I’m your child.”

“Well, yeah,” he said. “But you don’t take videos.”

He pocketed his other child, and we stood side by side, in awe of the stone fortress that was going to be my dorm, East Hall. All around us, families were unloading boxes and suitcases onto the sidewalk. Guys were shaking hands and thumping fists like old friends. It was a steamy day, and the huge oak tree near the front entrance was the only break from the hot sun. A few parents sat on the grass there, watching the car-to-dorm caravan. Cicadas buzzed and hissed, their invisible cacophony pressing into my inner ear.

“Well, they don’t make ’em like this back in Boulder,” Dad said. He was pointing to the old building, which was probably built before Boulder was even a city.

“That they don’t,” I said, the words nearly getting caught in my throat.

I felt as if every homework assignment I’d ever toiled over, every test I’d ever aced, it was all for a reason. Finally, here it was. My chance for a do-over. Here at Natick, I could be just Rafe. Not crazy Gavin and Opal’s colorful son. Not the “different” guy on the soccer team. Not the openly gay kid who had it all figured out.

Maybe from the outside, that’s what I looked like. I mean, yeah. I came out. First to my parents, in eighth grade, and then at Rangeview, freshman year. Because it’s an

open and accepting

school. A

safe

place

. And then my soccer team sat down and we had a team meeting, and then they knew. Extended family, friends of friends. Rafe. Gay.

And no one’s head exploded. And nobody got beat up, or threatened, or insulted. Not much, anyway. It all went pretty great.

Which is fine, but.

One day I woke up and I looked in the mirror, and this is what I saw:

Where had Rafe gone? Where was I? The image I saw was so two-dimensional that I couldn’t recognize myself in it. I was as invisible in the mirror as I was in the headline the Boulder

Daily Camera

had run a month earlier: Gay High School Student Speaks Out.

In truth, there were a lot of reasons I was moving across the country to attend Natick for my junior year. It was just that some of

those reasons would have been hard to explain to, let’s say, the president of Boulder’s Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays, because that person obviously wouldn’t understand that while they had made life easier for a gay kid, the gay kid still wanted to leave.

Especially when said PFLAG Boulder president is your mom.

So maybe I buried the truth a little. I mean, it wasn’t a lie to say that I wanted to go to a school like Harvard or Yale; I did. Mom was concerned an all-boys boarding school would be a homophobic environment, but I showed her that they not only had a Gay-Straight Alliance at Natick, but that the year before, they’d even had a former college football player who was gay come speak. There was this article in the

Boston Globe

about it, about how even a school like Natick was adjusting to the “new world order” where gay was okay. So she was satisfied. And unbeknownst to her, it was going to give me a chance to live a label-free life.

The night before, Dad and I had dinner at this Vietnamese restaurant in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. What Dad didn’t realize, as we sat there eating cellophane noodles and ground chicken wrapped in lettuce, was that I was silently saying good-bye to a part of myself: my label. That word that defined me as only one thing to everyone.

It was limiting me, big-time.

“Quarter for your thoughts?” Dad asked. Inflation, he explained.

“Just mulling,” I replied. I was thinking about how snakes shed their skin every year, and how awesome it would be if people did that too. In lots of ways, that’s what I was trying to do.

As of tomorrow, I was going to have new skin, and that skin could look like anything, would feel different than anything I knew

yet. And that made me feel a little bit like I was about to be born. Again.

But hopefully not Born Again.

Dad opened the hatchback and began to put my duffel bags and boxes on the hot concrete. Sweat beaded up on my forehead and dripped onto my upper lip as I struggled to lift a box that had been underneath the duffels. It was a wet heat, something I’d first experienced when we hit the Midwest, maybe Iowa. I’d never even been east of Colorado before the trip, and now here I was, about to live in New England.

It took us four long, sweaty trips up the stairs to the fourth floor to get all my stuff to my room. My roommate, a guy named Albie Harris, at least according to the e-mail I’d gotten, wasn’t around, but as we opened the door, we found that his stuff sure was.

Albie’s side of the room was messy. Like earthquake messy. The furnishings were all pretty standard stuff: linoleum floors, two faux wood desks side by side, two white dressers at the feet of two metal-framed single beds on opposite sides of the room. But a box of Cap’n Crunch was open and spilled across the floor. A pillow, sans pillow-case, had traveled across the room and was under my bed, along with a black T-shirt, a science textbook, and what appeared to be a fake nose and mustache attached to a pair of eyeglasses. He’d gotten here maybe one day before me, since the dorms just opened yesterday, yet there were at least five crumpled Sunkist soda cans underneath and around his unmade bed. Two open suitcases lay in the center of the room, still full but with clothes overflowing in all directions. On his desk was a pair of two-way radios, as well as another radio with tons of buttons. Above his bed was a huge, menacing poster that

depicted a car exploding. In big, bloodred letters at the bottom it read, S

URVIVAL

P

LANET

.

I looked at my dad and opened my eyes wide, and he got this half grin he gets when he is savoring something that he can use for later. I’m the kind of kid who keeps spare Swiffers in his closet, and he knew me well enough to know how horrified I was at the sight of this disaster area.

I flopped down on the bed the roommate had left untouched. Dad stood in the doorway and took out his iPhone, and I groaned.

“A perfect match,” he said, panning the room with his phone.

Nothing was more annoying than when my dad had an opinion, and it proved to be correct. For four months, and more vehemently for the 2,164 miles we’d just driven, he’d told me I was making a mistake. Normally, this would be my time to deny it, to insist he was wrong, but it seemed useless to argue. If my dad and mom could have paid my roommate to have my new room look like the worst possible home for me, this would have been it.

So I gave in. I put my head in my hands and shook it exaggeratedly, like I was really upset. “This does not bode well,” I said.

Dad laughed and came and sat next to me, putting his arm on my shoulder.

“Hey. It is what it is,” he said, always the great philosopher.

“I know, I know. I get to make my own choices and live with the consequences. I have free rein to make my own mistakes,” I said.

“Hey,” he said, shrugging. “The universe is infinite.”

In my dad’s language, that means,

I’m just a guy. What do I know?

He stood up. “You want me to help you unpack?” he asked, his tone that of a man who had a 2,164-mile return journey ahead of

him and really didn’t want to place polo shirts in dresser drawers just now.

“I can do it,” I said.

“You sure?”

“Yeah,” I said.

Dad walked to the window, so I joined him. My room was on the back side of the dorm, which faced the huge, grassy quad. Outside, guys were throwing Frisbees, congregating in small groups. Guys, all guys. Mostly preppy. Very New England conservative. It didn’t look that different from the pictures on the Internet, the photos that had gotten me interested in the first place. Very unlike what I could see of my roommate.

“You sure this is the right place for you?” he asked.

“I’ll be fine, Dad. Don’t worry about me.”

He stared out the window as if the whole place made him sad.

“Seamus Rafael Goldberg. At the Natick School. Doesn’t sound right, somehow,” Dad said.

Yes, my name is Seamus — pronounced SHAY-mus — Rafael Goldberg. Try being five with that name. They called me Seamus as a young kid, then Rafael, which is almost worse, until I was like ten. I picked

Rafe

when I was in fifth grade, and I have insisted on it ever since.

He crossed the room, leaving me alone at the window, and I watched this kid loft a Frisbee a good fifty yards.

Dad pointed the camera at me, and I winced.

“C’mon. One video for your mom,” he said, and I shrugged. I went to the middle of the room, next to the Cap’n Crunch spillage, and pointed down as if I were a tour guide at the Grand Canyon.

Dad laughed. Then I trotted over to my roommate’s bed, put my two hands together, and leaned my head on them as if to say,

I’m in love!

With the iPhone still recording, I walked back to the window, trying to come up with a funny pose. But then a strange thing happened. I felt this pang in my gut and I bit my lip. I’m not super big on emotional outbursts, which is what made it weird. I thought I might break down and start crying, starkly aware that as soon as Dad left, I’d have no one but strangers around me. Dad must have seen something in my body language, because he put his phone down, came back over to me, and gave me a sweat-soaked hug.

“Hey. You’re gonna be a rock star here, Rafe,” he whispered into my ear.

It was one of those things he always said, ever since I was five and going off to kindergarten. I was gonna be a rock star in the sand-box, I was gonna be a rock star in sixth-grade orchestra, and now I was gonna be a rock star at Natick.

“Love you, Dad,” I said, a little choked up.

“I know you do. We love you too, buddy. Go kick some ass, take some names,” he said, nearly tripping on the tipped-over cereal box as he let me go and stepped toward the door. “Find a boyfriend.”

I tensed up. That wasn’t exactly the thing I wanted broadcast in my first hour at Natick. Kids were walking by, but nobody stopped and looked.

“Give Mom a hug for me,” I said, and I hugged him one more time.

“One last video for the road?” he asked, pointing his iPhone back in my direction.

I put my hand in front of my face, as if I were a celebrity who was tired of having pictures taken. And really I was. Not a celebrity, but truly tired of being on camera.

When you’re Gavin and Opal’s gay kid, you always feel like someone is looking at you. Not necessarily in a bad way. Just looking. Because something about you is interesting and different. But what you don’t know is what they’re seeing. And that’s the kind of thing that could drive a guy crazy.

Dad took the hint and pocketed the phone for a final time. “Bye, son,” he said, as a sweet, inimitable smile creased his face.

“Bye, Dad.”

And he left me alone in my new world, staring at the semiblank slate that was my side of the room.