Oracle Bones (2 page)

Authors: Peter Hessler

Thieves developed the Luoyang spade, but during the first half of the twentieth century, Chinese archaeologists adopted the tool for their purposes. An experienced archaeologist can take a core from the deep earth, examine its

contents, and determine whether he stands above an ancient buried wall, or a tomb, or a rubbish pit. The dirt plugs reflect the meaning of what lies below; they are like words that can be recognized at a glance.

For years, Jing and the others have been reading the earth in this part of Anyang. They began with a systematic survey, digging holes across the fields and checking for signs of buried structures. One series of random corings turned up an object: tamped earth, twenty feet wide, lying six feet beneath the surface. As they surveyed the underground structure, they realized that it ran as straight as an arrow. They followed it across the soybean fields, accumulating tiny holes and piles of cores in their wake. Three hundred yards, a thousand yards—more holes, more cores. When the object suddenly stopped, they discovered a ninety-degree bend: a corner. At that point they realized that it must have been a settlement wall, and since then they have continued tracing the boundary and other interior structures. They are mapping a city that no living person has ever seen.

This is an early stage of archaeology; after the coring is finished, they will undertake more extensive excavations. But Jing never seems rushed to get there. He moves slowly, deliberately. He is thirty-seven years old, a friendly man with a quick smile, and his face is a work of simple geometry: round head, round cheeks, round-rimmed glasses. He grew up in Nanjing, but he studied archaeology at the University of Minnesota. His cultural references are broad and sometimes they catch me by surprise. During one of our walks above the underground city, he tells me to avoid thinking of the Shang as a dynasty in the political sense.

“A lot of people talk about the Shang as if it was very big,” he says. “They’re looking at the ancient state as if it were a modern state. People find Shang artifacts everywhere and they think, well, this region was part of the Shang state. But you have to make a distinction between cultural and political control. I would say that in terms of political entity it was actually very small—maybe no bigger than three river valleys. But the cultural influence was much bigger. It’s like if I buy McDonald’s here, you wouldn’t say that I’m in America. It’s the culture.”

THE PEASANTS SWEAT

in the autumn sunshine. Their poles move in an uneven line, following the invisible path of a buried wall. The men dig a hole, take a few steps, dig another hole. If you watched from a distance, without any concept of the underground city, the work would appear to be a meaningless ritual: peasants with poles, marching across the dry soil. A hole, a few steps, another hole. A peasant, a field, a road, a village. A hole, a few steps, another hole.

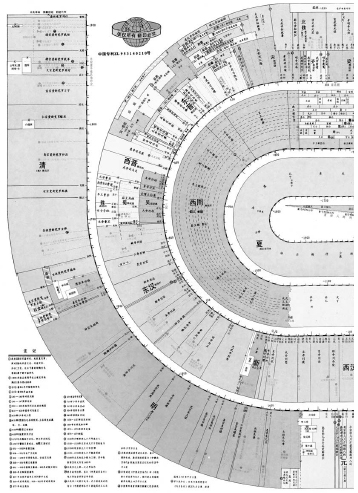

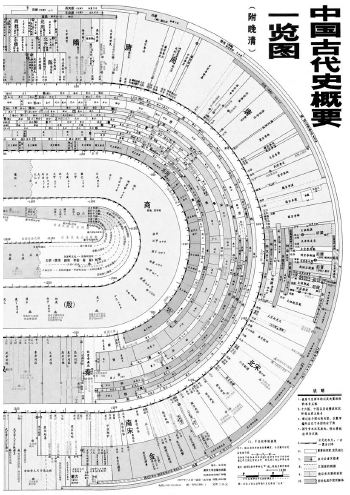

Outline of Ancient Chinese History

Outline of Ancient Chinese History

May 8, 1999

I WAS THE LAST CLIPPER AT THE BEIJING BUREAU OF THE

WALL STREET

Journal

. The bureau was cramped—two rooms and a converted kitchen—and the staff consisted of two foreign correspondents, a secretary, a driver, and a clipper. The driver and I shared the kitchen. My tools were a set of box cutters, a metal ruler, and a glass-covered desk. Every afternoon, the foreign newspapers were stacked above the desk. If an article about China seemed worthwhile, I spread the paper on the glass, carved out the story, and filed it in the cabinets at the back of the main office. They paid me five hundred American dollars every month.

The bureau was located in the downtown embassy district, a couple of miles from Tiananmen Square. In a neighborhood to the north, I found a cheap apartment to rent. It was a mixed area: old brick work-unit housing, some traditional

hutong

alleys, a luxury hotel. On one corner, next to the sidewalk, stood a big Pepsi billboard illuminated by floodlights. It was still possible to live quite simply in that part of the capital. Restaurants served lunch for less than a dollar, and I biked everywhere. When the spring evenings turned warm, young couples played badminton by the light of the Pepsi billboard.

At most other foreign bureaus in Beijing, clippers had already become obsolete, because everything was being computerized. In the old days, paper files had been necessary, and young people accepted the job because it provided an introduction to journalism. A clipper sometimes helped with research and, if a big news event broke, he might do some spot reporting. On the average, the

job required only a few hours a week, which left plenty of time for travel and freelance writing. A clipper could learn the ropes, publish some stories, and eventually become a real China correspondent. I had some previous experience in the country, teaching English and studying Chinese, but I had never worked as a journalist. I arrived in Beijing with three bags, a stack of traveler’s checks, and an open-ended return ticket from St. Louis. I was twenty-nine years old.

The small bureau was pleasant—the crisp smell of newspapers, the smattering of languages that echoed off the old tiled floors. The foreign staff and the secretary spoke both English and Chinese, and the driver was a heavyset man with a strong Beijing accent. While filing the clipped stories, I thought of the subject headings as another language that I would someday learn. The folders were arranged alphabetically, by topic:

DEMOCRACY

DEMOCRACY PARTY

DEMONSTRATIONS

DISABLED

DISASTERS

DISSIDENTS

Complicated topics were subdivided:

U.S.-CHINA—EXCHANGES

U.S.-CHINA—RELATIONS

U.S.-CHINA—SCANDAL

U.S.-CHINA—SUMMIT

U.S.-CHINA—TRADE

During my early days on the job, I hoped that the files could provide useful training. I often pulled a folder and read through dozens of stories, yellowed with age, all of them circling around the same topic. But inevitably I started skimming headlines; after a while, even the headlines bored me. To amuse myself while working, I read the file labels in alphabetical order, imagining possible storylines to connect them:

SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

SECRETS &

SPIES SECURITY

SEX

One section of

P

s read like a tragedy, complete with hubris, in all of six words:

PARTY

PATRIOTISM

POLITICAL REFORM

POPULATION

POVERTY

Another series seemed scrambled beyond comprehension:

STUDENTS

STYLE

SUPERPOWER—“NEW THREAT”

SUPERSTITION

TEA

Once, I pointed out this sequence to the bureau chief, who remarked that sooner or later every China correspondent has to write an article about tea. In May of 1999, when a United States B2 plane took off from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri, flew to Belgrade, and dropped a series of satellite-directed bombs on the Chinese embassy, killing three Chinese journalists, the

Wall Street Journal

created a new file:

U.S.-CHINA—EMBASSY BOMBING

. It fit next to

EXCHANGES

.

I HAPPENED TO

be in the southern city of Nanjing when the attack occurred. That was my first research trip: I planned to write a newspaper travel article about the history of the city, which had been the capital of China during various periods. Nanjing was the sort of place important events always seemed to march through on their way to some other destination. Over the centuries, various armies had occupied the city, and great leaders had come and gone, leaving nothing but tombs and silent memorials of stone. Even the name itself—“Southern Capital”—was a type of memory.

Artifacts had been strewn everywhere around Nanjing. Outside of town, the emperor Yongle of the Ming dynasty had commissioned the carving of the biggest stone tablet in the world as a memorial to his father, the dynastic founder. In 1421, Yongle moved the capital north to Beijing, for reasons that remain unclear, and his engineers left the tablet unfinished. Supposedly they had never figured out how they were going to move the object.

When I visited the stone tablet, there were only a handful of tourists at the site. The quarry was mostly overgrown, with young trees and low bushes creeping up the rolling hills. The abandoned memorial consisted of three parts: a broad base, an arched cap, and the main body of the tablet itself.

The limestone object lay on its side, as if some absentminded giant had set it down and then wandered away. It was 147 feet long, and the top edge stood as high as a three-story building. Over the centuries, straight streaks of rain runoff had stained the stone face, like lines on a child’s writing pad. Apart from those water marks, the surface was completely blank; nobody had ever gotten around to inscribing the intended memorial. Visitors could walk freely on top. There weren’t any rails.

A young woman named Yang Jun staffed the ticket booth. She was twenty years old, a country girl who had come to Nanjing to find work. Young people like her were flocking to cities all across the nation——more than one hundred million Chinese had migrated, mostly to the factory boomtowns of the southern coast. Social scientists described it as the largest peaceful migration in human history. This was China’s Industrial Revolution: a generation that would define the nation’s future.

At this historic moment, Yang Jun had found a job at the biggest blank slate in the world. When I asked her about the object, she looked bored and rattled off some statistics: it was fifty feet wide and fifteen feet thick, and supposedly the project had required the labor of one hundred thousand men. It weighed twenty-six thousand tons. I asked if there were many visitors, and she stared at me as if I were an idiot. “Tourists go to the Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum.” It sounded like an accusation: Why are you here?

I tried another angle. “Does anybody ever fall off the top?”

A light flickered in the woman’s eyes. “Two people did the year before last,” she said. “One of them jumped and one of them fell. The one who jumped had just been dumped by his girlfriend. Actually, he survived, but the guy who fell died.”

We chatted for a while, and the young woman kept returning with relish to those same details: the accident had resulted in death, whereas the attempted suicide had lived. Yang Jun seemed to be in a much better mood when I left. She told me that the heartbroken man had been permanently disfigured by his leap from the tablet.

IN

N

ANJING, I

collected everything in my notebook—scraps of conversation, museum labels, random observations. At the mountaintop mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen, an English sign caught my eye:

THE MAP OF THE WHOLE MAUSOLEUM LOOKS LIKE AN ALARM BELL, WHICH SYMBOLIZES THE NEVER-ENDING STRUGGLING SPIRIT OF DR. SUN YAT-SEN

AND HIS DEVOTION OF HIMSELF TO THE CAUSE OF WAKING UP THE MASSES AND SAVING THE CHINESE NATION AND STATE

Sun Yat-sen had been a key leader in the movement to overthrow China’s last imperial dynasty, the Qing, which ruled until 1911. At the mausoleum, vendors sold a set of commemorative lapel pins dedicated to what the People’s Republic believed to be the trinity of great twentieth-century Chinese leaders: Sun Yat-sen, Mao Zedong, and Deng Xiaoping. Each man’s profile was accompanied by his most distinctive slogan, and the three sentences lined up neatly on a strip of cardboard: