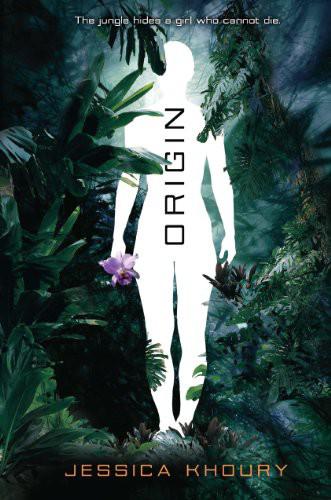

Origin

Authors: Jessica Khoury

Tags: #Romance, #Fantasy, #Young Adult, #Adventure, #Science Fiction

JESSICA KHOURY

An Imprint of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Origin

RAZORBILL

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Young Readers Group

345 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario,

Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre,

Panchsheel Park, New Delhi – 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand

(a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank,

Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Copyright © 2012 Jessica Khoury

ISBN: 978-1-101-59072-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

ALWAYS LEARNING

PEARSON

FOR BEN.

ALWAYS.

ONE

I

’m told that the day I was born, Uncle Paolo held me against his white lab coat and whispered, “She is perfect.” Sixteen years later, they’re still repeating the word. Every day I hear it, from the scientists or the guards, from my mother or from my Aunt Brigid.

Perfect

.

They say other things too. That there are no others like me, at least not yet. That I am the pinnacle of mankind, a goddess born of mortal flesh.

You are immortal, Pia, and you are perfect,

they say.

But as I follow Uncle Paolo to the laboratory, my bootlaces trailing in the mud and my hands clutching a struggling sparrow, the last thing I feel is perfect.

Outside the compound, the jungle is more restless than usual. The wind, lightly scented with orchids, prowls through the kapoks and palms as if searching for something it lost. The air is so damp that drops of water appear, almost magically, on my skin and on Uncle Paolo’s pepper-gray hair. When we pass

through the garden, the heavy-hanging passionflowers and spiky heliconias brush against my legs, depositing dew onto the tops of my boots. Water is everywhere, just like every other day in the rainforest. But today it feels colder—less refreshing and more invasive.

Today is a testing day. They are called the Wickham tests, and they only come every few months, often by surprise. When I awoke in my glass-walled bedroom this morning, I expected the usual: reciting genus and species lists to Uncle Antonio, comparing algae specimens under microscopes with Uncle Jakob, followed, perhaps, by a long swim in the pool. But instead, I was greeted by Mother, who informed me that Uncle Paolo had decided to hold a test. She then breezed out the door and left me scrambling to get ready. I didn’t even have a chance to tie my shoelaces.

Hardly ten minutes later, here I am.

The bird in my hands fights relentlessly, scratching my palms with his tiny talons and snapping at my fingertips with his beak. It does no good. His claws are sharp enough to break the skin—just not

my

skin. That’s probably why Uncle Paolo told me to carry the bird instead of doing it himself.

Indestructible it may be, but my skin feels three sizes too small, and it’s all I can do to keep my breathing steady. My heart flutters more frantically than the bird.

Testing day.

The last test I took, four months ago, didn’t involve a live animal, but it was still difficult to pass. I had to observe five different people—Jacques the cook, Clarence the janitor, and other nonscientist residents—to calculate whether they contributed more to the welfare of Little Cam than it cost to feed,

pay, and keep them. I was terrified that my findings would result in someone being fired. No one was, but Uncle Paolo did have a talk with Aunt Nénine, the laundress, about how much time she spent napping compared with the time she spent keeping up with the wash. I asked Uncle Paolo what the test would prove, and he told me it would show whether my judgment was clear enough to make rational, scientific observations. But I’m still not sure Aunt Nénine has forgiven me for my report, rational observations or not.

I look down at the sparrow and wonder what’s in store for him. For a moment, my will—and my fingers—weaken only slightly, but it’s enough for the bird to jerk free and launch into the air. My enhanced reflexes make a decision faster than my brain: my hand reaches out, closes around the bird in midair, and draws him back to me, all in the time it takes the eye to blink.

“Everything all right?” Uncle Paolo asks without turning.

“Yes, fine.” I know he knows what just happened. He always does. But he also knows I would never be so disobedient as to let his chosen specimen fly free.

I’m sorry

, I want to say to the bird.

Instead, I hold on tighter.

There are two lab buildings in Little Cam. We arrive at B Labs, in the smaller one, and Mother is waiting inside. She wears her crisp, white lab assistant’s coat and is pulling on latex gloves. They snap against her wrists.

“Is everything ready, Sylvia?” Uncle Paolo asks.

She nods and leads the way, passing door after door. We finally stop in front of a small, rarely used lab near the old wing, which was destroyed in a fire years ago. The door to the

ruined hall is locked, and from the rust on the doorknob I can tell it hasn’t been opened in years.

Inside the lab, metal shelves and cabinets and sinks line the walls, and they all catch and distort my reflection. In the center of the room is a small aluminum table, with two chairs on either side and a metal cage on its surface.

“Put subject 557 inside,” Uncle Paolo says, and I release the bird into the cage, which is just large enough for him to fly in a tight circle. He throws himself at the metal grate, then lands, wings spread awkwardly, on the bottom. After a moment he launches up again, beating his wings determinedly against his captivity.

Then I notice the wires snaking from the cage to the table, down and across the floor, to a small generator under the emergency eyewash station.

I miss a breath, then glance at Uncle Paolo to see if he noticed. He didn’t. He’s filling out some forms on a clipboard.

“All right, Pia,” he says as his pen scratches away. The bird lands again, takes off, clutches the side of the cage with his small talons. Uncle Paolo hands me the clipboard. “Take a seat. Good. Did you bring a pen?”

I didn’t, so he gives me his and pulls another from his coat pocket. “What do I do?” I ask.

“Take notes. Measure everything. This particular test subject has been given periodic doses of a new serum I’ve been developing with suma.”

Suma.

Pfaffia paniculata

, a common enough stimulant, but there are probably dozens of uses for it we haven’t discovered yet. “So…we’re testing to see if the subject handles

the…stress of this test better than an untreated control subject.”

“Right,” he says with a smile. “Excellent, Pia. This serum—I call it E13—should kick in when the bird has exhausted the last of its strength, giving it another few minutes of energy.”

I nod in understanding. Such a serum could prove useful in a myriad of medicinal ways.

“No computers today,” Uncle Paolo tells me. “No instruments. Just rely on your own faculties. Observe. Record. Later we’ll evaluate. You know the process.”

“Yes.” My eyes flicker to the bird. “I do.”

“Sylvia!” Uncle Paolo snaps his fingers at my mother, and she flips a switch on the generator. I feel the electricity before it hits the cage, a low vibration that sizzles through the wires by my feet. The hairs on my arms begin to rise as if the electricity were pumping into

me

.

The cage begins to hum, and the bird shrieks and jerks into the air, only to collide with the metal and get shocked again. I lean forward and watch and

see

the moment the bird realizes he can’t land. His pupils constrict, his feathers flare, and he begins wheeling in tight, dizzying loops.

I feel nauseated, but I dare not let Uncle Paolo see. He leans back, hands folded on his own clipboard. He isn’t here to observe the sparrow.

He’s here to observe me.

I bow my head and force myself to write something down.

Ammodramus aurifrons—yellow-browed sparrow, usually found in less dense areas of the rainforest

. I look up again, watching the bird. Watching Uncle Paolo watching me. I keep every

muscle in my face perfectly still and draw each breath deliberately, slow and even. I can’t let him see me wince, or gasp, or anything that might indicate my emotions are hindering my objectivity. The bird tries to land again, and I hear the snap and sizzle of the electricity. Already weary, the helpless sparrow resumes his frenetic circling.

In flight for 3.85 minutes

, I jot down.

At 9.2 wing beats per sec =2097.6 beats…flight for 2.4 minutes…

The numbers are all reflex to me. The scientists like to tease me about it, saying I spend too much time with them. Once I responded, “Who else is there?” They never replied to that.

The sparrow is beginning to make mistakes. His wings grow clumsy, earning him more frequent shocks. At one point he seizes the metal bars in his talons and flattens himself against the side of the cage, tiny body shuddering with electricity.

I know Uncle Paolo’s eyes are on me, searching for any sign of weakness. It’s all I can do not to wince.

I can’t fail this. I

can’t

. Of all my studies, the Wickham tests are the most important. They gauge whether I am ready to be a scientist. Whether I’m ready for the secrets of my own existence. Once I prove I’m one of them, my real work can begin: creating others like me. And that is everything. I am the first and only of my kind, and I’ve been the first and only for sixteen years. Now, there is only one thing I want: someone else who knows. Knows what it is to never bleed. Knows what it is to look ahead and see eternity.

Knows what it is to be surrounded by faces that you love, faces that will one day stop breathing and start to decay while your own will remain frozen outside of time.

None of them know. Not Mother, not Uncle Paolo, not

any of them. They think they can understand. They think they can empathize or imagine with me. But all they really know is what they can observe, such as how fast I can run or how quickly bruises on my skin can fade. When it comes to the hidden part of me, the inner, untouchable Pia, all they can really know is that I’m different.