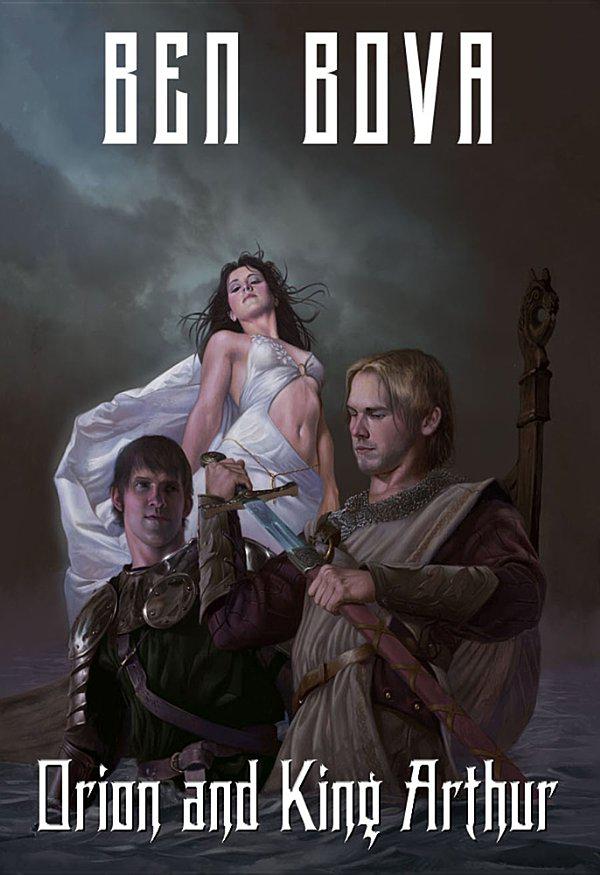

Orion and King Arthur

To my tennis buddies: good friends and true

Contents

Chapter Seven: Wroxeter and Cameliard

Chapter Eight: The Sword of Kingship

Chapter Nine: Leodegrance’s Wedding Gift

Chapter Eleven: Castle Tintagel

Chapter Twelve: Guinevere and Lancelot

Chapter Thirteen: The Lady of the Lake

Chapter Fourteen: Morganna and Modred

Chapter Fifteen: The Battle of Camlann

Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.

—Abraham Lincoln

Prologue: Heorot

1

For the first time that bitterly cold winter, Heorot was bright again, ringing with song and a king’s gratitude to the hero.

And then the beast roared, out in the icy darkness.

“But he’s dead!” King Hrothgar bellowed, pointing to the shaggy monster’s arm that now was affixed over the mead-hall’s entrance doorway.

“I killed him,” exclaimed Beowulf, “with these bare hands.”

Hrothgar turned to his queen, Wealhtheow, sitting beside him on the dais between the royal torches. She was as beautiful as a starry spring night, her raven-dark hair tumbling past her shoulders, her lustrous gray eyes focused beyond the beyond.

Wealhtheow was a seer. Gripping the carved arms of her throne, shuddering under the spell of her magic, she pronounced in a hollow voice, “The monster

is truly dead. Now its mother has come to claim vengeance upon us.”

Hrothgar turned as white as his beard. His thanes, who had been sloshing mead and singing their old battle songs, fell into the silence of cold terror.

The captives from Britain huddled together in sudden fear in the far corner of the hall. I could see the dread on their faces. Hrothgar had sworn to sacrifice them to his gods

if Beowulf had not killed the monster. For a few brief hours they had thought they would be freed. Now the horror had returned.

I turned to gaze upon the lovely Queen Wealhtheow. She was much younger than Hrothgar, yet her divine gray eyes seemed to hold the wisdom of eternity. And she was staring directly at me.

How and why I was in Heorot I had no idea. I could remember nothing beyond the

day we had arrived on the Scylding shore, pulling on the oars of our longboat against the freezing spray of the tide.

My name is Orion, that much I knew. And I serve Beowulf, hero of the Geats, who had sailed here to Daneland to kill the monster that had turned timbered Heorot, the hall of the stag, from King Hrothgar’s great pride to his great sorrow.

For months the monster had stalked Heorot,

striking by night when the warriors had drunk themselves into mead-besotted dreams. At length none would enter the great hall, not even stubborn old Hrothgar himself. Until Beowulf arrived with the fourteen of us and loudly proclaimed that he would kill the beast that very night.

Beowulf was a huge warrior, two axe handles across the shoulders, with flaxen braids to his waist and eyes as clear

blue as the icy waters of a fiord. Strength he had, and courage. Also, he was a boaster of unparalleled brashness.

The very night he came to Heorot with his fourteen companions he swaggered so hard that narrow-eyed Unferth, the most cunning of the Scylding thanes, tried to take him down a peg. Beowulf bested him in a bragging contest and won the roars of Hrothgar’s mead-soaked companions.

After

midnight Hrothgar and his Scyldings left the hall. The torches were put out, the hearth fire sank to low, glowering embers. It was freezing cold; I could hear the wind moaning outside. Beowulf and the rest of us stretched out to sleep. My shirt of chain mail felt like ice against my skin. I dilated my peripheral blood vessels and increased my heart rate to make myself warmer, without even asking

myself how I knew to do this.

I had volunteered to stay awake and keep watch. I could go for days without sleep and the others were glad to let me do it. We had all drunk many tankards of honey-sweetened mead, yet my body burned away its effects almost immediately. I felt alert, aware, strong.

Through the keening wind and bitter chill I could sense the monster shambling about in the night outside,

looking for more victims to slaughter.

I sat up and grasped my sword an instant before the beast burst through the massive double doors of the mead-hall, snarling and slavering. The others scattered in every direction, shrieking, eyes wide with fear.

I felt terror grip my heart, too. As I stared at the approaching monster I recalled a giant cave bear, in another time, another life. It had ripped

me apart with its razor-sharp claws. It had crushed my bones in its fanged jaws. It had killed me.

Beowulf leaped to his feet and charged straight at the monster. It rose onto its hind legs, twice the height of a warrior, and knocked Beowulf aside with a swat of one mighty paw. His sword went flying out of his hand as he landed flat on his back with a thud that shook the pounded-earth floor.

Everything seemed to slow down into a dreamy, sluggish lethargy. I saw Beowulf scrambling to his feet, but slowly, languidly, as if he moved through a thick invisible quagmire. I could see the beast’s eyes moving in its head, globs of spittle forming between its pointed teeth and dropping slowly, slowly to the earthen floor.

Beowulf charged again, bare-handed this time. The monster focused on

him, spread its forelegs apart as if to embrace this pitiful fool and then crush him. I ducked beneath those sharp-clawed paws and rammed my sword into the beast’s belly, up to the hilt, and then hacksawed upward.

Blood spurted over me. The monster bellowed with pain and fury and knocked me sideways across the hall. Beowulf leaped on its back, as leisurely as in a dream. The others were gathering

their senses now, hacking at the beast with their swords. I got to my feet just as the brute dropped ponderously back onto all fours and started for the shattered door, my sword still jammed into its gut.

One of the men got too close and the monster snatched him in its jaws and crushed the life out of him. I shuddered at the memory, but I took up Beowulf’s dropped sword and swung as hard as I

could at the beast’s shoulder. The blade hit bone and stuck. The beast howled again and tried to shake Beowulf off its back. He pitched forward, grabbed at the sword sticking in its shoulder, and wormed it through the tendons of the joint like a butcher carving a roast.

Howling, the monster shook free of him again, but Beowulf clutched its leg while the rest of us hacked away. Blood splattered

everywhere, men roared and screamed.

And then the beast shambled for the door, with Beowulf still clutching its leg. The leg tore off and the monster stumbled out into the night, howling with pain, its life’s blood spurting from its wounds.

That was why we feasted and sang at Heorot the following night. Until the beast’s mother roared its cry of vengeance against us.

“I raid the coast of Britain,”

Hrothgar cried angrily, “and sack the cities of the Franks. Yet in my own hall I must cower like a weak woman!”

“Fear not, mighty king,” Beowulf answered bravely. “Just as I killed the monster will I slay its mother. And this time I will do it alone!”

Absolute silence fell over Heorot.

Then the king spoke. “Do this and you can have your choice of reward. Anything in my kingdom will be yours!”

Before Beowulf could reply, sly Unferth spoke up. “You have no sword, mighty warrior.”

“It was carried off by the dying monster,” Beowulf said.

“Here then, take mine.” Unferth unbuckled the sword at his waist and handed it to the hero.

The hall fell absolutely silent. Giving one’s sword to another was a mark of the highest respect, even admiration. Unferth could pay Beowulf no higher honor.

Yet it seemed to me that Unferth was dissembling. I saw hatred glittering in his cold reptilian eyes.

Beowulf pulled the blade from its scabbard and whistled it through the air. “A good blade and true. I will return it you, Unferth, with the monster’s blood on it.”

Everyone shouted approval, especially the British captives. There were an even dozen of them: eleven young boys and girls, none

yet in their teens, and a wizened old man with big, staring eyes and a beard even whiter than Hrothgar’s.

The monster roared outside again, and silenced the cheers.

Beowulf strode to the patched-up door of the mead-hall, Unferth’s sword in his mighty right hand.

“Let no one follow me!” he cried.

No one did. We all stood stunned and silent as he marched out into the dark. I turned slightly

and saw that Unferth was smiling cruelly, his lips forming a single word: “Fool.”

2

“Orion.” Queen Wealhtheow called my name.

She stepped down from the royal dais and walked through the crowd toward me. The others seemed frozen, like statues, staring sightlessly at the door. Hrothgar did not move, did not even breathe, as his queen approached me. The Scylding thanes, Beowulf’s other companions,

even the frightened British captives—none of them blinked or breathed or twitched.

“They are in stasis, Orion,” Wealhtheow said as she came within arm’s reach of me. “They can neither see nor hear us.”

Those infinite gray eyes of hers seemed to show me worlds upon worlds, lifetimes I had led—we had led together—in other epochs, other worldlines.

“Do you remember me, Orion?”

“I love you,” I

whispered, knowing it was true. “I have loved you through all of spacetime.”

“Yes, my love. What more do you remember?”

It was like clawing at a high smooth stone wall. I shook my head. “Nothing. I don’t even know why I’m here—why you’re here.”

“You remember nothing of the Creators? Of your previous missions?”

“The Creators.” Vaguely I recalled godlike men and women. “Aten.”

“Yes,” she said.

“Aten.”

Aten had created me and sent me through spacetime to do his bidding. Haughty and mad with power, he called me his tool, his hunter. More often I was an assassin for him.

“I remember … the snow, the time of eternal cold.” But it was all like the misty tendrils of a dream, wafting away even as I reached for them.

“I was with you then,” she said.

“The cave bear. It killed me.” I could

feel the pain of my ribs being crushed, hear my own screams drowned in spouting blood.

“You’ve lived many lives.”

“And died many deaths.”

“Yes, my poor darling. You have suffered much.”

I remembered her name: Anya. She was one of the Creators, I realized. I loved a goddess. And she loved me. Yet we were destined to be torn away from each other, time and again, over the eons and light-years

of the continuum.

“This beast that ravaged Heorot was not a natural animal,” she told me. “It was engendered and controlled by one of the Creators.”

“Which one? Aten?”

She shook her head. “It makes no difference. I am here to see that the beast does not succeed. You must help me.”

Deep in my innermost memories I recalled that the Creators squabbled among themselves like spoiled children. They

directed the course of human history and sent minions such as me to points in spacetime to carry out their whims. Many times I have killed for Aten, and many times have I died for him. Yet he brings me back, sneering at my pains and fears, and sends me out again.

I am powerless to resist his commands—he thinks. But more than once I have defied his wishes. At Troy I helped Odysseos and his Achaeans

to triumph. Deep in interstellar space I led whole fleets into battle against him.

“Has Aten sent me here, or have you?” I asked her.

She smiled at me, a smile that could warm a glacier. “I have brought you here, Orion, to help Beowulf slay both monsters.”

“Is Beowulf one of your creatures?”

She laughed. “That bragging oaf? No, my darling, he is as mortal as a blade of grass.”

“But why is

this important?” I asked. “Why has your enemy used these beasts to attack Heorot?”

“That I will explain after you have helped Beowulf to kill the second monster.”

“If I live through the ordeal,” I said, feeling sullen, resentful.