Orphan of Angel Street (54 page)

Paul and Grace both dealt with these surprises with perfect courtesy and gladness. Mercy took huge delight in introducing him to the boys – ‘my half-brothers’ – and to Dorothy.

‘Dorothy Finch is—’

‘I remember you talking about Dorothy,’ Paul said.

Dorothy’s eyes were welling with emotion.

‘Yes, but Dorothy is my auntie – oh Dorothy, come here!’ Both very tearful they hugged and hugged each other.

‘You don’t know how often I’ve wanted to tell you,’ Dorothy sobbed, ‘only I couldn’t.’

Mercy took Paul’s arm. She felt she wanted to hold and hug everyone around her all day long. ‘If you’re all confused we’ll explain on the way back,’ she said. She looked round anxiously. ‘You will come back, won’t you?’

‘Well,’ Grace was uncertain. ‘If Mabel doesn’t mind.’

‘She won’t,’ Mercy said firmly. Suddenly she broke away from Paul, and for the first time in her life, went to Mabel and kissed her cheek.

‘You be happy now,’ she said. ‘You just make sure.’

Mabel looked startled, then grinned. ‘I’ll do me best.’ She patted Mercy on the arm.

The wedding party made its unhurried, celebratory way back along the Moseley Road, Mercy, in the middle of it, arm and arm with her mother and her husband-to-be.

Grace looked round at her beautiful, indomitable daughter, who had in the last hour transformed into someone lit up by great happiness. Grace, too, was full of a calmness and joy she had not experienced for many, many years. A sense of rightness and completion. She was not anxious about her husband. She had kept Mercy from him for twenty years and she would continue to do so. The rest of them would not let her down. Neville was an irrelevance.

But there was one anxiety. Her eyes met Mercy’s and then she glanced at Paul.

Does he know? her eyes queried. Does he know the truth?

Mercy’s eyes shone back at her full of deep, unclouded joy.

He knows, hers responded. He knows. And he forgives.

Grace smiled and squeezed her arm. Bless you, that loving pressure said. Bless you, my darling. Be happy.

Margaret Adair picked up the letter from the table in the hall and frowned at the rather childish hand.

‘What’s that?’ Stevie said, full of questions as ever.

Margaret patted his head rather absently. ‘A letter. I don’t know who from. You go on upstairs now, darling, and see how Nanny’s getting on with the twins’ breakfast. Then she’ll take you all out.’

She took the letter into the sitting room and sat by the window, slitting open the envelope.

The address at the top provided no enlightenment. It was simply ‘Birmingham, May 1923.’

Dear Mrs Adair,

I’ve been meaning to write to you for such a long time to apologize for leaving you and Stevie the sudden way I did. I was sorry to do it, especially with you having the baby on the way. There were some bad problems in my family and I had to go. I hope you can forgive me. I did miss you.

I expect Stevie is a big boy by now and has forgotten me long ago. But please give him a big kiss and cuddle from me.

You might like to know that I’m married. My husband is an engineer working at the Austin, and we have two children and another on the way. Our two little girls are called Susannah and Elizabeth and they are very healthy and full of energy.

We had a very special surprise last year. I had met, after many years, a Mr Joseph Hanley who founded the home where I started life and we had become friends. I’m sad to say he died last year, but he left me a tidy little sum of money which has been a great blessing for our family life.

We are all in good health and hope you are too. My warmest regards to you and your family. Perhaps one day we shall meet again.

Yours,

Mercy (née Hanley)

Margaret read the letter twice, with a mixture of emotions. She had been hurt and saddened by Mercy’s mysterious flight from their house, had worried about her, and was delighted with news of her happiness. Yet something about the letter troubled her. Mercy’s reasons for leaving them that way didn’t seem quite right. Surely she had been on bad terms with her family such as it was? And why could she not have have talked her troubles over, not dashed off like that as if she were eloping?

‘Who’s that from?’ James popped his head round the door before setting off for work.

Margaret looked up. ‘It’s the strangest thing. It’s from Mercy – little Mercy Hanley – you remember?’

The immense pang which passed through James Adair’s heart at the mention of her name did not register in his face. He stepped into the room, hands in trouser pockets.

‘Our little fly-by-night? Ah yes – what news of her?’

‘She sounds very well. She’s married, two little girls already. But she doesn’t say who to.’ She turned the paper this way and that. ‘No address or anything.’

‘Hmm. Curious. Still, there we are. And you say she’s well and happy?’

‘Seems to be, yes. I’m glad for her. Odd business that, altogether.’

‘Odd, yes . . .’ James said dismissively. ‘Anyway, must go. Give Stevie and the girls a kiss for me will you? I’m in a bit of a hurry.’

‘All right, dear. Have a good day.’

James left, then on second thoughts came back and unexpectedly kissed her cheek, caressed her shoulder.

‘Goodbye, my darling.’

She smiled up at him in happy surprise.

Some days later, the postman pushed a thin, cheap envelope through the letter box of a terraced house in Bournbrook which had a climbing honeysuckle lazing, sweetly scented, up its front wall.

Mercy picked it up in the hall as Paul came downstairs with the two girls. Susannah, determined to walk down by herself had a mass of blonde curly hair like a corona with the light from the landing window behind her, and striking dark brown eyes. The little one, Elizabeth, in Paul’s arms, was unmistakably going to have his long, sensitive face and brown hair.

Paul sat Elizabeth down on the hall floor. ‘There now, miss, you can crawl about – and keep off the stairs.’

He crept up behind Mercy and caught her by the waist, stroking her swollen stomach. The baby was due in four months.

‘Your family coming round in droves today?’

Mercy laughed. Paul loved teasing her about her family, Grace’s and Dorothy’s eagerness to share her children, and the house was hardly ever quiet. Even after nearly three years of marriage she was still in a state of wonder at the richness of her life. The love of her family, and this house, their house, to which she could welcome them, with space and running water and a generous strip of garden for the girls out at the back. Paul had just built Susannah a swing from the pear tree.

‘Oh, I dare say someone will be round!’ she said.

Paul rested his head against the back of hers for a moment. Her hair was hanging loose and he lifted a hank of it to kiss the back of her neck.

‘Look,’ she said, squirming with pleasure. ‘From America.’

They read it together, he over her shoulder.

‘Yola and Tomek!’ Mercy said. ‘Oh – they’ve moved again, look – the address is new. Maybe now they’ll have a bit more space for all these babbies of theirs.’

Yola already had three and was due with the fourth.

The letter was very short. Slowly, gradually they were learning to write English as well as speak it.

‘

WE ARE ALL GOOD

,’ Tomek had written carefully in capital letters. ‘

NEW PLACE IS GOOD. YOLA HAS A BABY BOY

.’

‘Oh, lovely!’ Mercy exclaimed.

‘EVERYTHING FINE. WE HAVE FOOD AND GOODS. WE ARE ALL FINE AND HOPE YOU TOO FINE. LIFE IS GOOD. TOMEK PETROWSKI.’

‘Life is good.’ Mercy turned in Paul’s arms, still holding the fragile letter. She felt her embrace returned with equal passion and gratitude.

‘It is, isn’t it?’ she said. ‘Very, very good.’

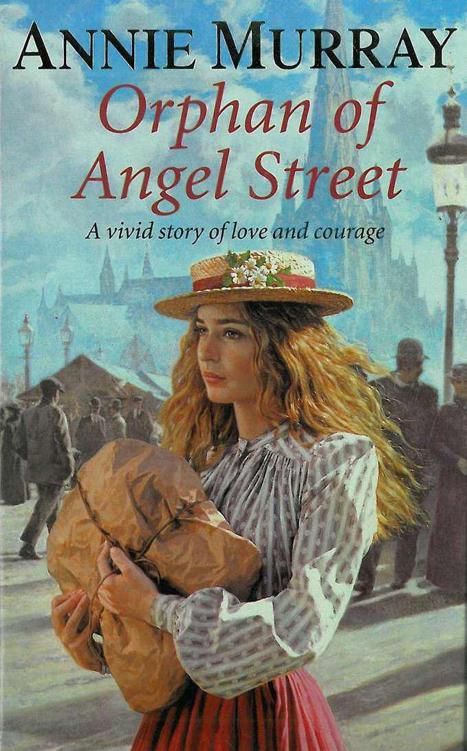

Annie Murray was born in Berkshire and read English at St John’s College, Oxford. Her first ‘Birmingham’ novel,

Birmingham Rose

, hit

The Times

bestseller list when it was published in 1995. She has subsequently written many other successful novels, including, most recently,

The Bells of Bournville Green

. Annie Murray has four children and lives in Reading.

Also by Annie Murray

Birmingham Rose

Birmingham Friends

Birmingham Blitz

Poppy Day

The Narrowboat Girl

Water Gypsies

Chocolate Girls

Miss Purdy’s Class

Family of Women

Where Earth Meets Sky

The Bells of Bournville Green

For Rachel, in memory of a Mashhad taxi ride

With special thanks to Mike Price, Jonathan Davidson, and to Birmingham City Council Library Services for their help and support.

First published 1999 by Macmillan

This edition published 2001 by Pan Books

This electronic edition published 2010 by Pan Books

an imprint of Pan Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited

Pan Macmillan, 20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

ISBN 978-0-330-52787-3 PDF

ISBN 978-0-330-52786-6 EPUB

Copyright © Annie Murray 1999

The author and publishers would like to thank Mr Hugh Nayes for permission to quote from ‘The Victorious Dead’ by Alfred Noyes, taken from

The Elfin Artist and Other Poems

published by William Blackwood & Sons in 1920.

The right of Annie Murray to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Visit

www.panmacmillan.com

to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you're always first to hear about our new releases.