Oscar Wilde and the Vatican Murders (38 page)

Read Oscar Wilde and the Vatican Murders Online

Authors: Gyles Brandreth

‘In any

event, he was not long for this world,’ said Munthe, transferring his gaze from

Oscar to the champagne glass before him. ‘He was not a well man.’

‘It was

you who prescribed him strychnine, Doctor—’

‘Yes,’

answered Munthe, looking up sharply, ‘But not a lethal dose or anything like

one. Very occasionally I gave him a thousandth of a grain, as a stimulant, and

I administered it personally.’

‘Were

you in Rome on the day that little Agnes died —on 7 February 1878?’

Munthe

looked perplexed. ‘On the day that Pope Pius IX died? Yes, as it happens, I

was. I was a student, aged twenty, on my first trip to Italy.’

‘And

you went to the Vatican that day?’

‘I did,

out of curiosity. I was not alone. The pope was dying — all Rome knew that.’

‘So you

were there,

locus in quo,

on the day that little Agnes died.’

Munthe

laughed. ‘I was, but I did not kill her. I do assure you of that. And I did not

kill Tuminello.’

‘Do not

protest too much, Doctor. Are you not, like Keats, by your own admission, “half

in love with easeful death”?’

‘I did

not kill the child, Agnes. I did not kill Monsignor Tuminello.’

‘If you

didn’t, then who did, I wonder?’ Oscar raised his champagne glass to his lips

and looked out across the grand piazza.

I

smiled. ‘You believe you know, don’t you, Oscar?’

‘I

believe I do, Arthur. And, God willing, tomorrow afternoon, over tea at the

Capuchin church, all will be revealed. And Arthur, while I explain the mystery,

you can serve the cucumber sandwiches.’

22

Old bones

T

he

austere and elegant church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini was

commissioned by Pope Urban VIII in the year 1626 at the instigation of his

younger brother, Cardinal Antonio Barberini, who was both powerful and of the

Capuchin order. In 1631, on the church’s completion, Barberini commanded that

the mortal remains of thousands of Capuchin friars be exhumed and transferred

from the old Capuchin friary of the Holy Cross near by to the crypt of the new

church of the Immaculate Conception. There, over time, in five interconnecting

subterranean chapels, the bones of more than four thousand Capuchins were laid

to rest. They were neither buried nor entombed but displayed: as a celebration

of the dead and a reminder to the living. Bones —

thousands of bones

—

laid out in extraordinary, elaborate, ornamental patterns, adorn the walls and

ceilings of the church crypt. Complete skeletons, some dressed in Franciscan

habits, lie or sit or crouch in dark corners and individual niches. A plaque in

one of the chapels reads: ‘What you are now, we once were; what we are now, you

shall be.’

It was

at this bizarre ossuary that Oscar chose to host his English tea party and

bring what he termed ‘the drama of the Vatican murders’ to its climax. It was

in this dimly lit gallery of bones and skeletons that he insisted that I hand

round cups of Indian tea and plates of cucumber sandwiches (thinly sliced and

lightly salted). To my astonishment, the Capuchin church was happy to allow my

friend to commandeer the crypt for his divertissement. Indeed, it turned out

that the priest in charge had a ‘set fee’ for an afternoon’s hire of the crypt

and since Brother Matteo, a good Capuchin and friend to the church, was to be

of the party, and Oscar was ready to pay four times the going rate, there were

no awkward questions asked.

To my

delight, Catherine English agreed to help me with the refreshments. The

sandwiches were not a problem. It turned out that in the larder of her

apartment at All Saints she had a ready supply of bread she had baked in the

English manner; I bought fresh cucumbers from the vegetable market on Piazza

Barberini, and Darjeeling tea from the English tea-rooms by the Spanish Steps.

And at the church of the Immaculate Conception we found a stove, a kettle and

sufficient crockery for our purpose in the pantry adjacent to the crypt.

The

guests were invited for four o’clock and all came, in good order and in good

humour — in remarkably good humour, I thought, under the circumstances.

‘They

are excited by the prospect of hearing your story,’ Oscar whispered to me

teasingly.

‘They

will be disappointed, then,’ I said.

‘A

little disconcerted, perhaps, but when they hear what I have to offer in its

place I believe their attention will be held.’

The

trio of chaplains-in-residence from the Vatican were the first to arrive.

Monsignor Felici, the Pontifical Master of Ceremonies, vast and wheezing, but

with a twinkle in his eye, descended the crypt’s stone steps, gripping Brother

Matteo by the arm. The friar, stalwart, upright, equable as ever, though

returned from Capri only that lunchtime, betrayed no sign of weariness. When I

asked after Father Bechetti’s funeral, he nodded gently and said simply,

‘E

andato bene, grazie.’

Monsignor Breakspear brought up the rear, bubbling

with bonhomie.

‘I love

this church,’ he declared to no one in particular. ‘Urban VIII was brought up

by Jesuits, of course. He

was

urbane, arguably the most civilised of all

the popes. As we can tell from Caravaggio’s portrait, he was wonderfully

handsome. He had a brilliant mind and exquisite taste. He got the better of

Galileo in debate. He wrote fine poetry and beautiful prose.’ Breakspear caught

my eye and beamed at me. ‘He would have enjoyed your work, Conan Doyle. If only

poor Tuminello was still with us, he might have been able to summon up Urban’s

ghost to listen to your story this afternoon.’

I

smiled wanly at the Grand Penitentiary and offered him a cucumber sandwich.

‘The

Lord be praised,’ he breathed. ‘These do look like the real thing.’ He took a

bite of a sandwich and gazed about him. We were standing in the ‘crypt of

skulls’, the empty eye-sockets of a legion of dead Capuchins staring down at

us. ‘Perhaps Tuminello

can

hear us,’ he said, ‘and Father Bechetti too.

And Pope Urban …’

‘And

Pio Nono?’ suggested Oscar, joining the group.

‘Pio

Nono was very hard of hearing towards the end,’ said Monsignor Breakspear,

beaming at me once more. ‘Be sure to speak up during your reading, Conan

Doyle.’

Hurriedly

I moved away, mumbling that I had to be about my butler’s duties. I took my

dish of sandwiches through to the ‘crypt of the pelvises’, where I found the

Reverend Martin English, Axel Munthe and James Rennell Rodd, teacups in hand,

standing in a semicircle and peering up at a ceiling rosette formed by seven shoulder

blades set in a frame of sacral bones, vertebrae and feet.

‘We

don’t do this sort of thing in England, do we?’ murmured Rennell Rodd. ‘I’m

glad.’ He looked at my plate of sandwiches. ‘This is more like it,’ he said.

Truth

to tell, everyone at the gathering seemed more taken with the tea and

sandwiches than the extraordinary

memento mori

all around them. Indeed,

everyone, it appeared, apart from Oscar and myself, knew the crypt already.

‘It has

been a tourist attraction since the eighteenth century,’ Axel Munthe explained.

‘The Marquis de Sade, Hans Andersen, Mark Twain: they’ve all written it up.

When you’ve been to St Peter’s and seen the

Pietà,

this is where you

come next.’

‘The

English do come,’ said Rennell Rodd, ‘but rarely more than once. It’s not

terribly jolly, is it?’

‘We

Swedes come time and time again,’ replied Axel Munthe, pleasantly. ‘We find it

very soothing.’

At half

past four, Oscar, checking his watch, called the assembly to order.

‘Ladies

and gentlemen, there are chairs laid out in the last chapel. Please make your

way there now. Miss English and Dr Conan Doyle will bring through further

refreshments. We are nearly all gathered, I think. We’re just waiting on Cesare

Verdi, then we can begin.’

There

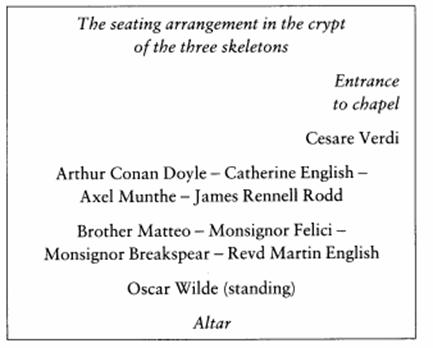

was no dilly-dallying. The assembly moved eagerly along the vaulted corridor to

the last room, the ‘crypt of the three skeletons’, where Oscar had arranged

nine chairs in rows facing the altar.

The

four clergymen, without prompting, filled up the front row, with the Capuchin

friar at one end, the Anglican chaplain at the other and the two Monsignors in

pride of place between. Once Miss English had topped up the teacups and I had

finished serving the sandwiches, we took our places in the second row,

alongside James Rennell Rodd, who remarked loudly as we joined him, ‘Don’t let

Wilde hog the limelight with his preliminaries. It’s your story we’ve come for,

Conan Doyle.’

‘And a

tale of Sherlock Holmes is what you are about to receive, James,’ declared

Oscar, standing centre-stage before us. ‘But on this occasion, forgive me,

it’ll be I who tells the story, not Arthur.’

‘The

man’s incorrigible,’ grumbled Rennell Rodd. ‘I should not have come.’

‘I am

glad that you did, James,’ said Oscar, unperturbed. ‘You have a significant

part to play in what’s to come.’

From

the front row Nicholas Breakspear looked up at Oscar and enquired tartly: ‘We

are getting a Sherlock Holmes story, aren’t we, Mr Wilde? That is what we were

promised.’

‘It all

begins with Sherlock Holmes,’ said Oscar, tantalisingly, checking his watch

once more, then looking behind him at the candles flickering on the altar. He

glanced at the skeletons, bones and vertebrae that lay all around. Peering into

the enveloping gloom, he smiled as Cesare Verdi — unshaven, dressed in an

unseasonable wool suit and holding a brown bowler hat — appeared beneath the

archway. ‘Ah, you’ve arrived,’ said Oscar.

Verdi

raised a hand as if to speak, but Oscar stopped him.

‘Please,’

said Oscar, ‘take a seat, then we can begin.’

‘Yes,’

muttered Rennell Rodd. ‘Let’s get on with it.’

Verdi

took his seat in the half-light in the back row by the doorway. Oscar gazed

upon the assembled company with apparent satisfaction. Catherine English smiled

at me and whispered softly, ‘This is exciting.’ She pressed her fingers gently

on my sleeve. I looked around at the expectant faces all fixed on Oscar and

thought to myself, If there is a murderer in our midst, he is either a mighty

cool customer or he has no notion of what Oscar has in store.