Our One Common Country (12 page)

Read Our One Common Country Online

Authors: James B. Conroy

Members of Congress, Stephens said, were “children in politics and statesmanship,” whom he schooled against Davis unabashedly. At one point, Davis offered to resign if Stephens would, but refused to hand the Confederacy to a man who would surrender it at once to Grant. Giving up on it all, Stephens spent most of the war sulking in Georgia, urging its legislature to pressure Davis and Congress alike, visiting Richmond only briefly to harass them at close quarters.

Despite his ferocity when crossed, a friend called Little Alec “as simple and genial in his manners as a child.” Made rich by investments in land, he paid for the educations of scores of poor young men. “As I had been assisted when in need,” he said, “so I ever afterward assisted those in like circumstances, as far as I could.” His Crawfordville, Georgia, estateâcalled Liberty Hallâwas graced with a house of the second or third tier. Eliza, his housekeeper, had instructions to feed all uninvited visitors who came to its door, which suffered no shortage of invitees. Liberty Hall's mealtimes were synchronized with the train schedule. Eliza's husband, Harry, oversaw the plantation in Stephens's absence. A newspaperman interviewed him about its owner, “Mars Alec,” Harry called him (“Master Alec” in Harry's dialect). “He is kind to folks that nobody else will be kind to,” Harry said. “Mars Alec is kinder to dogs than mos' folks is to folks.” The folks to whom Mars Alec was said to be kind included Harry, Eliza, their five little children, and the other human beings enslaved at Liberty Hall.

“God knows my views on slavery never rose from any disposition to lord it over any human being,” Stephens said, “or to see anybody else so lord it. In my whole intercourse with the black race, those by our laws recognized as my slaves [an uncomfortable circumlocution] and all others, I sought to be governed by the Golden Rule. I never owned one that I would have held a day without his or her free will and consent.” By 1845 he owned ten. He eventually accumulated about 5,000 acres and the slaves who worked them.

Harry nursed him through his illnesses and managed the other slaves, the only overseer Stephens had. The field hands Stephens treated like laboring wards. He housed, fed, and clothed them comfortably; had them taught to read and write, defying the laws against it; never punished them physically; never sold them; bought relatives he didn't need; cared for them in sickness and old age. Harry and Eliza's children, Ellen, Fanny, Dora, Tim, and Quinn, did odd jobs and played more often than they worked.

After one of his slaves “got in trouble with a white woman,” another slave said, Stephens gave him money and told him to go away.

When Harry had asked his leave to marry Eliza, Stephens had written from Washington to his brother, mixing kindness with condescension. “Say to him I have no objection. And tell Eliza to go to Solomon & Henry's and get a wedding dress, including a fine pair of shoes, etc., and to have a decent wedding of it. Let them cook a supper and have such of their friends as they wish. Tell them to get some âparson man' and be married like Christian folks. Let the wedding come off when you are at home so that you can keep good order among them. Buy a pig, and let them have a good supper.” Like other gentle racists uneasy with the word, Stephens referred to his society's forced-labor system as “so-called” slavery, “which was with us, or should be, nothing but the proper subordination of the inferior African race to the superior white.”

What came to be known as “The Cornerstone Speech” was the blunder of his career. He delivered it in Savannah a month after his inauguration as vice president. It alienated Europe, motivated the North, and energized the abolitionists. Jefferson and many of his elite contemporaries had thought that slavery was wrong, Stephens said, an evil to be eliminated, a premise based on equality of the races. “This was an error.” The Confederacy's “cornerstone rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and normal condition.” Stephens cared nothing for the thought that a nation built on slavery would repel the civilized world, certain as he was that “if we are true to ourselves and the principles for which we contend, we are obliged to, and must triumph.”

No less than he had before the war, Vice President Stephens aspired to the role of peacemaker. In June of 1863, with Lee's army full of hubris on its way to Pennsylvania, he sought Davis's permission to go to Hampton Roads and discuss a prisoner exchange at Fort Monroe. Treading on eggshells in a letter to his president, he mentioned a grander goal. “I am not without hope that

indirectly

I could now turn attention to a general adjustment upon such basis as might ultimately be acceptable to both parties and stop the further effusion of blood in a contest so irrational, unchristian, and so inconsistent with all recognized American principles.” Davis let him go, and Stephens took a steamer to Fort Monroe. Lincoln wanted to see him. His Cabinet talked him out of it. Lee had been beaten at Gettysburg, Grant had taken Vicksburg, and the Yankees turned Stephens away, leaving him humiliated and Davis gloating.

In 1864 he was talking peace again. If the North would simply recognize the sovereignty of the states, Stephens believed, the war would stop immediately and “the great law of nature” would determine their proper union, in the old one or a new. “But you might as well sing psalms to a dead horse, I fear, as to preach such doctrines to Mr. Lincoln, and those who control that government, at this time.”

In September 1864, Sherman sent a message inviting Stephens to captured Atlanta to negotiate a peace plan. Stephens replied that peace commended itself “to every well-wisher of his country.” He would sacrifice anything short of honor to achieve it, but he had no power to negotiate it, and nor, it seemed to him, did Sherman. If the general would say there was any chance for terms to which their respective governments might agree, he would devote himself “cheerfully and willingly” to restoring a just and honorable peace to “the country.” He closed optimistically. “This does not seem to me to be at all impossible, if truth and reason should be permitted to have their full sway.”

Sherman had no such authority.

PART II

We Are But One People

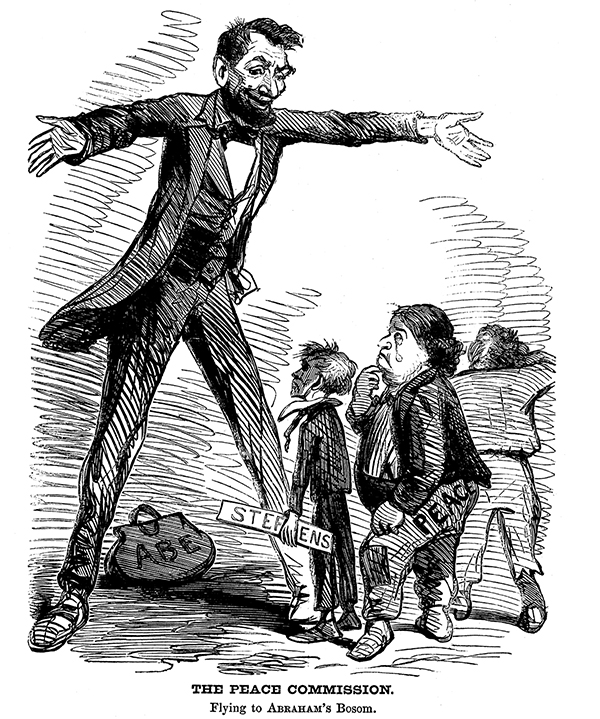

Harper's Weekly,

February 18, 1865

Reprinted Courtesy of Applewood Books, Carlisle, MA

CHAPTER TEN

A Treachery Unworthy of Men of Honor

General Josiah Gorgas presided over the Southern armaments industry, having built it almost from scratch. A balding, bearded West Point graduate from Pennsylvania, one of a handful of Northern-born generals in gray, he had sided with his wife, an Alabama governor's daughter, when the officer corps broke up. On January 4, 1865, after passing a pleasant wedding anniversary over supper and cards at home, he confided to his diary how depressed Richmond was. “Still, gaiety continues among the young people, and there is much marriage and giving in marriage. We were last night at a ball at Judge Campbell's, where dancing was kept up until 4 thirty in the morning.” The gaiety was surely enhanced by the judge's lovely daughter, whom a smitten young officer had admired at a recent wedding as “the striking girl in pink.”

But her father was in no dancing mood. The hapless commissary general had confessed that day that he could no longer feed the army. It was plain to Judge Campbell that the adjutant and the inspector general were incompetent too, though everyone, in fairness, had been dealt a barren hand. Campbell shared his dismay with General Gorgas as the young people flirted and danced. Gorgas was shaken too. “Is the cause really hopeless? Is it to be abandoned and lost in this way?”

As Assistant Secretary of War, Campbell was preparing a report to Secretary Seddon on eight urgent needs that must be met immediately if the war could go on at all. Seddon told the judge that Davis had been advised to consult now and then with the leading men in Congress, his critics as well as his friends, and received the idea with a frigid stare. Campbell asked what plans the president had to meet the current emergency. Seddon said he had none.

In the Confederate House of Representatives, a motion was made to pay a courtesy call on the president. A roll call vote was required after dissidents shouted it down.

On December 3, Alec Stephens had returned to Richmond with a terrible cold and a bladder attack. He had been gone a year and a half, long enough to notice the city's decay. The

Examiner

's Edward Pollard called it “a time when all thoughtful persons walked with bent heads.” On January 6, the vice president addressed the Senate in secret session. Independence could still be had, he said, but the government must reverse almost all of its policies. Stop drafting proud men, and deserters will return; keep an army in the field for a year or two more, anywhere at all (an implied exhortation to abandon Richmond), avoiding battle whenever possible, and the North will wear down, broken by expense and its people's pleas for peace, despite its overpowering strength. Congress should demand negotiations now, conditioned only on the sovereignty of the states and their right to choose their own alignments.

On January 7, the worried War Department clerk John Jones saw Judge Campbell gravely beckon his friend Senator Hunter into his office. There was talk of Davis and Stephens both resigning. With the cautious Hunter next in line as president pro tempore of the Senate, Lee would be in charge as a practical matter. In a letter from Georgia, Davis was told that Savannah was submitting meeklyâthat the spirit of resistance in the rest of the state was dissolving. The shock of Sherman's cruelty had paralyzed it. There is “every indication that many people are almost prepared to abandon the struggle and submit to the Yankee yoke, with the hope of saving their property.” Some despondent Rebels thought Grant would be spared the trouble of taking Richmond. The Confederacy was melting from within.

On January 5, former senator Orville Hickman Browning went to the White House again, looking for a pass to Richmond for James Singleton, Lincoln's friendly enemy. Singleton's Southern trading expedition was

about to be launched in partnership with Browning. A retired federal judge was a partner too, and a sitting senator from New York, all of them friends of Lincoln's. Grant was hotly opposed to

any

Southern trade, but Lincoln believed that its benefits, including the satisfaction of the army's need for cottonâfor uniforms, tents, and bandagesâoutweighed its risks. He gave Singleton a pass to cross the lines “with ordinary baggage” and return “with Southern products.” While he was down there, Lincoln said, he might find six hundred bales of cotton that Mrs. Lincoln's half sister had mislaid, ardent Rebel though she was.

Singleton, like Blair, had friends in high Southern places. He would later say that Lincoln authorized him to tell them that, if they accepted reunion, the Emancipation Proclamation would be left to the courts, and he had no power to push abolition further.

Preston Blair had committed his peace proposal to writing, “which was done & tied up nicely,” his daughter Lizzie wrote her husband, Phil. He was full of his plans for a happy result, Lizzie said, though discretion prevented her from disclosing the particulars. Neither father nor daughter was sanguine about his chances, but Lizzie told Phil that he felt very well. She had never seen him work so hard or so happily.

On Friday, January 6, even before he left, the Richmond press had gotten wind of his plans.

something wicked this way comes

was the

Examiner

's delicious headline. “We would not be superstitious, but we seem to perceive in the air a taint of sulphitic odors of Washington.” It would soon be plain “what particular piece of Yankee villainy and treachery lurks under the unofficial visit of Blair, Sr. and Blair, Jr. within our lines.” Presumably they were spies. A pair of “Hebrew blockade-runners would be more welcome.” In the light most favorable to him, old Blair was “an officious busybody in a state of second childhood.” President Davis should be pleased to welcome peace commissioners to Richmond if they came to acknowledge its independence, but not to “entertain spies as the honored guests of the Confederacy.” The

Whig

was of the same mind. To supplement their spying, the Blairs were sure to add the “cool impudence” of a proposition that the North would not subjugate the Southern people

if they only pled contrition. It was “absolutely delightful.” They “richly deserve hanging.”

The

Examiner

and the

Whig

were always hard on Davis, but the

Sentinel

was his voice, and the

Sentinel

would reserve judgment until the Blairs had disclosed their errand. If they came on behalf of the Lincoln administration, to abandon its unjust war, nothing could be more welcome. If they came to spy and sow discord, they would “add fresh insult, and attempt a treachery unworthy of men of honor. We will stand on our guard and await developments.”

In Washington, the debate continued in the House of Representatives on the amendment banning slavery, its critics positioning abolition as a threat to peace and reunion. As mayor of New York in 1861, Fernando Wood had proposed to lead her out of the Union and take her cotton trade with her. Now he was a Copperhead congressman, though Thaddeus Stevens considered him no statesman. “Nay, sir, he will not even rise to the dignity of a respectable demagogue.” In a passionate speech to the House, Wood said abolition would make it impossible to restore the Union on the old order of things.

Sunset Cox was inclined to agree. “So long as there is a faint hope of a returning Union, I will not place obstacles in the path.” If abolition could bring reunion, Cox would vote to embrace it. “But as it stands today, I believe that this amendment is an obstacle to the rehabilitation of the States.” The key phrase here was

as it stands today.

In the wake of their recent meeting, Cox would wait and see whether Lincoln offered peace to Richmond.

On January 6, a hard rain fell on Blair House as its patriarch huddled past midnight with Horace Greeley and other unpaid consultants, their papers and persons splayed across the heirloom furniture, driving the women of the house upstairs. The old man left the next morning on the naval steamer

Don,

the Potomac flotilla's flagship, on a fifteen-hour trip to Hampton Roads and Fort Monroe, accompanied by his freed black

servant Henry and the

Don

's attentive officers, conscious of his status as a president's friend and an admiral's father-in-law.

Blair and Henry spent three days at City Point as arrangements were made to convey them to the Confederacy. If Blair had not confided his mission to Grant when he'd first come to City Point a week earlier, he did so now, leaving the general better informed than the president, and considerably more enthused. The old man shared with Grant what Lincoln had chosen not to hearâa startling secret plan to end the war, involving Mexico.

Mexico had been graced with seventy-five presidents in the forty-four years since the Spanish had been expelled in 1821, and Europe was not alone in casting greedy eyes on her silver, gold, and land and her apparent inability to defend them. The spoils of the Mexican War had only fed American ambitions, especially in the South, where planters looked to Mexico and saw warm, fertile ground for slavery. Northerners were looking too. Seward had a dream of absorbing and democratizing the whole continent, not excepting Alaska.