Our One Common Country (3 page)

Read Our One Common Country Online

Authors: James B. Conroy

But officers and orders still reigned. At the eastern end of the siege line, two miles away from the momentous happenings, an artillery officer in blue peered out from Fort McGilvery at an enemy team at work on their fortifications, a

faux pas during a truce, and decided to break it up. The Rebels scattered promptly, but their own artillery replied. The commotion remained local but continued until dark, rumbling down the siege

line. To the sound of distant cannon, a Rebel general made a stirring address, or so said the

Petersburg Express.

The defenders of the South must not let down their guard “on account of the so-called peace commission,” but “depend on their arms” for the peace that would come from their “manly exertions.” The man from the

Express

did not hear the oration, but understood that it generated much enthusiasm.

There was surely much enthusiasm when the lightning word was flashed that the peacemakers were coming. Rebel troops lined the Petersburg road and spilled out into the fields as a coach passed by on a wave of jubilation. When it pulled up behind the Confederate lines, the celebrities stepped down, attended by the mayor and the gracious Colonel Hatch. Slaves unloaded their trunks and joy washed over their heads as they parted a cheering crowd of buoyant Southern men and beaming Southern women down from Petersburg to witness history in their hoop skirts and bonnets. One of the three commissioners looked plump and rosy, another stiff and formal. The third, a sickly little Georgian, had been Lincoln's friend and ally in the old Congress. Now he was leaning on the arm of a slave, feeble but excited.

Not everyone was. A former Buffalo newspaperman had lost 70 of the 135 companions who had started the war with him. As the bitter Yankee saw it, the Southern peace commission emerged to the sound of protesting cannon, as “the hazy mist, which is not unusual here at sunset, began to obscure the distant horizon and give the landscape a gloomy and somber aspect. At first as we watched, they seemed as shadows moving in the hazy light, but as they approached their forms became clear and distinct, and we soon stood face to face with the representatives of treason, tyranny and wrong.”

Not as traitors but as dignitaries, the Southerners were saluted by a party of Northern officers and escorted to the Union lines. As a thousand troops on both sides chanted “Peace! Peace! Peace!” an excited Rebel soldier called for “three cheers and a tiger for the whole Yankee army,” and got them. The Yanks returned the favor, and a loud Northern voice demanded the same for the ladies, who waved their “snowy handkerchiefs” in decorous reply. Behind the Union lines, a gleaming horse-drawn ambulance was waiting to take the Southerners to the train that would

bring them to Grant. A team of matched horses drove them smartly away. By accident or design, all four of them were gray.

As darkness fell, the artillery duel up the line petered out. The federal officer in charge would soon recount his losses almost cheerfully. “I have no casualties to report among the artillery and but two killed and four wounded among the infantry.” It is safe to assume that the brass took the news in stride and the dead boys' families took it harder.

General George G. Meade, the celebrated victor at Gettysburg, came to visit the Rebel ambassadors the next day and wrote to his wife that night. One of them had asked to be remembered to her family. Another had brought a letter addressed to their common kin. Skeptical though he was, Meade had his hopes for peace. “I do most earnestly pray that something may result from this movement.”

Lincoln was prayerful too, old at fifty-five with the weight of 600,000 dead. A portrait painter named Carpenter had been living with him for weeks, absorbing “the saddest face I ever knew. There were days when I could scarcely look into it without crying.”

In the previous spring, after three cautious years of indecisive battle, Grant had taken command of all the Union armies and designed a new kind of war with the help of a brash subordinate, General William Tecumseh Sherman. “Sanguinary war,” Grant called itâbloody warâand Lincoln had given it his blessing. While Sherman attacked General Joseph Johnston's outnumbered Army of Tennessee and another Union force marched on Richmond, Grant and Meade would bludgeon Lee until he stopped struggling. In May and June alone, the North had sustained some 95,000 casualties. The South's horrific losses were unreliably counted. Lincoln had barely slept. Carpenter came across him in a corridor, “clad in a long morning wrapper, arching back and forth a narrow passage leading to one of the windows, his hands behind him, great black rings under his eyes, his head bent forward upon his breast.”

Tens of thousands of young Americans had lost their lives since then, and the war was not yet won. On his way to Hampton Roads to see an old friend from Georgia, Lincoln had a chance to end it.

PART I

Friends in Power

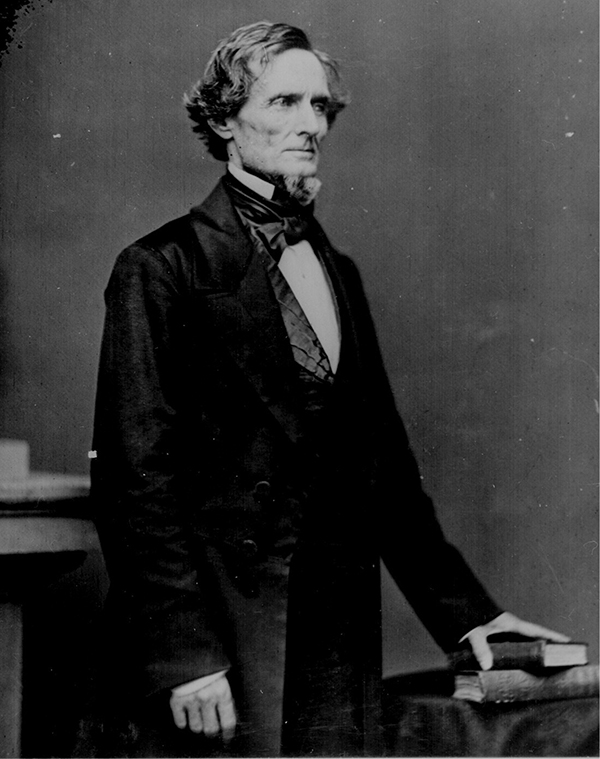

Jefferson Davis before the war

NATIONAL ARCHIVES

CHAPTER ONE

A Self-Immolating Devotion to Duty

On a trip to the infant Confederacy in the spring of 1861, the

Times of London

's American correspondent was presented to its president and found himself faintly surprised. The gaunt Mississippian was “a very different looking man from Mr. Lincoln,” remarkably “like a gentleman,” reserved, erect, and austere. Despite his noble bearing, he welcomed his foreign visitor in “a rustic suit of slate-colored stuff,” a slight, “care-worn, pain-drawn” man of little more than middle height. Though William Howard Russell had expected a grander figure, the Rebel leader's cigar commended him to his guest. “Wonderful to relate, he does not chew, and is neat and clean-looking, with hair trimmed and boots brushed,” distinctions worth mentioning on the Western side of the Atlantic, Jefferson Davis not excepted.

To Russell's keen ear, Jeff Davis's speaking style was laced with “Yankee peculiarities,” attributable, no doubt, to four years at West Point, seven in the US Army, and a dozen in Washington City. He had taken the public stage as a promising young congressman in 1845, left in 1846 to serve in the Mexican War, fought as a wounded hero at the head of the Mississippi Rifles, accepted an appointment to replace a departed senator, served with great distinction as Franklin Pierce's Secretary of War, and returned to Capitol Hill as the South's charismatic champion in the Senate. The New Yorker William Seward had called his friend and adversary “a splendid embodiment of manhood.” Their colleague Sam Houston had taken a different view. “Ambitious as Lucifer and cold as a lizard.”

Now he told his British guest that the people he led were a military people who would earn support with their deeds. “As for our motives, we meet the eye of Heaven.”

Always confident of Heaven's favor, Davis could not have earned it through consistency. In the antebellum years, he had wrestled with himself as much as his critics, professing in a single speech a “superstitious reverence for the union” and a willingness to serve as a standard bearer for secession. In 1858, he had led the Southern moderates in the Democratic Party, promoting national unity at Faneuil Hall in Boston, embracing the flag in Maine. Less than two years later he was leading the South to disunion. From his desk at the

Richmond Examiner,

an able young editorialist by the name of Edward Pollard saw a “record of insincerity which cannot be overlooked.”

There was no risk of Pollard overlooking it. As one Rebel officer said, the

Examiner

's

very mission was to torture its country's president, and the

Examiner

was not alone. For much of the Southern press, everything Davis did was wrong. Though a passion for states' rights was the Confederacy's very reason for being, its president grasped the need for a strong central government while it fought the North for its life. Unprecedented taxes, an ever-expanding draft, public takings of private property to keep the war going, and arrests without trial for its dissidents (all of which Lincoln pursued more aggressively in the North) had subjected Jeff Davis to peals of public outrage almost from the start. His temperament did not help. A Virginian expressed the common view. The president at first had been thought to be a mule, but a good mule, and had turned out to be a jackass; honest and hardworking but a poor judge of men, blind to the flaws of his pets, unforgiving of his critics, irritable, unbending, and hair-splitting. Distracted by petty disputes with governors, senators, and generals, he had his loyal friends, but his enemies were as petulant as he.

His devotion to General Braxton Bragg reminded a senator from South Carolina of “the blind and gloating love of a mother for a deformed and misshapen offspring.” It was not a happy polity.

By the summer of 1864, Davis's confidence was undimmed, but three horrific years fighting Yankees in the field and schools of sharks in Richmond had not improved his looks or brightened his disposition. Regal in his youth, he was spectral at fifty-six, with a hollow-cheeked face and a clouded left eye that could see only darkness and light. His right hand and arm often shook from a painful nerve disease. More often than not,

his armies had outfought the North and were still more than dangerous, but the war had bled them pale. One tubercular draftee was conscripted for ten days' service and died on the eleventh. Most of the Confederacy's wealth was spent. A naval blockade was strangling it. The loss of the Mississippi had cut it in two. Much of its territory was gone. Its people were demoralized. Demands for negotiations gained ground in its bickering Congress. In Georgia and North Carolina, there were rumblings in high places about a separate peace.

None of it moved Jeff Davis, who was heard to say unflinchingly that the people of the South would eat rats, and their twelve- and fourteen-year-old sons would “have their trial” before this war was over. With his faith in the divine protection of the cause he led intact, he spoke in public and private as one who owned the truth, dismissing his misinformed critics, as Edward Pollard said, with “the air of one born to command.”

His birth, in fact, had been humble. He came into the world in a Kentucky log cabin scarcely grander than Lincoln's, eight months before him and less than a hundred miles away; but the Davises moved to Mississippi and prospered, and fortune dealt Jeff a sibling twenty-four years his senior who parlayed the practice of law into land and slaves, plucked his little brother from a one-room school, had him educated properly, polished the results himself, gave him his own plantation, and taught him how to run it. The product was the near equivalent of the planter aristocracy, lacking only the pedigree, but the pedigree could not be fixed, and it barred him from his culture's inner ring, accounting, perhaps, for the fragility beneath the hauteur. His devoted wife, Varina, knew how easy it was to wound him, “a nervous dyspeptic,” she said, ill-served by a “repellent manner,” so thin-skinned that even a child's disapproval discomposed him.

According to Varina, her husband was easily persuaded where a principle was not at stake, but principles were everywhere in the mind of Jefferson Davis. He “could not comprehend” how any informed observer might differ with him on a point of public policy, and suspected insincerity in anyone who did. Years before the war, he had chastised his fellow senators on the Compromise of 1850, “proud in the consciousness of my own rectitude,” regarding “degraded letter writers” with “the indifference which belongs to the assurance that I am right, and the security with

which the approval of my constituents invests me.” Debating a Northern Democrat, he abhorred the very notion of compromiseâthat senators of the same party might construe the Constitution differently and cooperate politically. “I do not believe that this is the path of safety. I am sure it is not the way of honor.” As commander in chief of the Confederacy, his Secretary of the Navy said, Davis never doubted his military genius. After the twin disasters at Gettysburg and Vicksburg in 1863, he confessed to Robert E. Lee that nothing required “a greater effort of patience than to bear the criticisms of the ignorant.”

Varina helped him bear them. At the gracious Executive Mansion on Clay Street, she bantered with his guests on the novels they had read and the romances they were handicapping, and discussed the issues of the day with all of the president's brains, none of his knack for gratuitous provocation, and “admirable flashes of humor.” Her husband emitted no such flashes. He would materialize at her soirees an hour after they started, endure in near silence the talk of lesser men, ignore the opinions of the ignorant, shake ten or twenty hands in his “not over cordial grasp,” and excuse himself to his study.

He was capable of grace and a winning smile, but the cruel whip of sarcasm was his only brand of humor. There was no frivolity in him. He took careful note of the wardrobes of Richmond's ladies and described one that displeased him as “very high-colored” and “full of tags, and you could see her afar off.”

All of that said, he was far from cruel or insensitive. “I wish I could see my father,” his little daughter Maggie once said when her mother disciplined her; “he would let me be bad.” Desperate letters from desperate people broke his heart. “Poor creature, and my hands are tied!” He had truly loved the Union, treasured his Northern friends, watched their children grow from infancy to adolescence. Now their boys were of military age. Varina called their parting “death in life.” In his final speech to the Senate, her husband's voice had cracked as he wished them farewell. Not so cold a lizard after all.

In his own time and place, his attitudes on race were progressive. He greeted his slaves with handshakes and bows, made one of them his overseer, submitted their transgressions to the judgment of other slaves, and strictly forbade the lash. He endorsed the conventional rationalization

that their bondage had brought them from heathen darkness into Christian civilization but embraced the most progressive view that a Southerner could espouse and remain on the public stage: Over time, Christianity, education, and discipline would make the slave unfit for slavery.

Upright to a fault, he lashed himself to a code of honor so rigid as to allow for no exceptions, however disproportionate the consequences. Varina counted among his virtues “a self-immolating devotion to duty.” When the war began in Charleston in 1861, he rejoiced at the news that the only blood spilled at Fort Sumter had been a mule's, and told Varina with some hope that a final separation was still avoidable; but once Southern men had died for independence, there was no place for reconciliation in his psyche.

“This struggle must continue until the enemy is beaten out of his vain confidence in our subjugation. Then and not til then will it be possible to treat of peace.”

In the summer of 1864, the chance for independence was very much alive. The South was in extremis, but the North was wearing down. A little over a year before, while surprising and routing a much larger Union army, Stonewall Jackson had been killed at Chancellorsville, shot in the dark by confused North Carolinians, but Jackson and Robert E. Lee had left 11,000 Northerners dead or writhing on the field, 6,000 captured or missing, and Lincoln crying out in despair, “My God, my God. What will the country say?”

In the wake of the disaster, Colonel James Jacques of the 73rd Illinois, an ordained Methodist minister, had asked the president's leave to undertake a peace mission to his coreligionists in Richmond. Lincoln let him go, anticipating neither good nor ill. Some Southern doves broke bread with the Reverend Colonel but Davis would not see him. Jacques rejoined his regiment in time for Chickamauga. Another Rebel victory. Another 16,000 Union casualties.

In the spring of 1864, over 55,000

of Grant's men and boys had been killed, wounded, or captured in the space of six weeks, exceeding the eight-year toll of the American Revolution. Lee had done better, taking something in the range of 40,000 casualties, but the South could not

replace them, and Lincoln kept sending more men, not to mention more boys. Measured in blood alone, Grant was winning his sanguinary war, but the voters of the North were choking on it. Mary Todd Lincoln was “half wild” with letters from their mothers, wives, and sisters. Nearly every Northern village had lost a favorite son, and the end was not in sight. Davis's six-year term had two years to run, but Lincoln's was expiring, and the Democrats were the party of peace. Another four months of bleeding could not win the war for the South, but could lose it for the North if the Rebels held on until Election Day.