Out of Oz: The Final Volume in the Wicked Years (32 page)

Read Out of Oz: The Final Volume in the Wicked Years Online

Authors: Gregory Maguire

Tags: #Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Fairy Tales; Folklore & Mythology

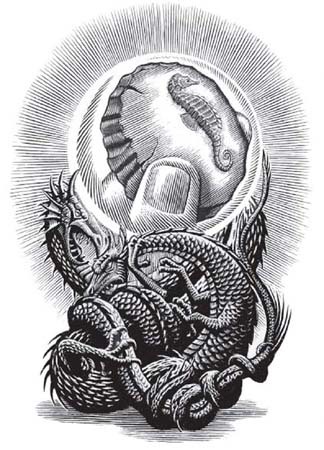

“But get on where?” he asked her, as they righted the husk of the Clock. The broken dragon head cantilevered forward, eyeless and insensate.

“Where are you going? And alone? Or is there a companion?”

“You’re so coy.”

“Stay with me, now,” said Ilianora to Rain. “Keep close.” But the girl paid her no more attention than she ever had.

“I’m causing trouble,” said Muhlama to Brrr, tossing her head toward Ilianora. “Pity.”

“Only so much I can do,” replied the Lion, equivocating.

That night Brrr asked of the companions, “

Are

we going our separate ways?” Muhlama, having said she would deliver them to their party in the morning, had taken herself off for a hike, to give the companions privacy to confer. “I mean, there can be no company of the Clock of the Time Dragon anymore, can there, if there is no Clock?”

“It’s resting. It’s caled Time Out,” said the dwarf, back to his old beligerence.

“The Lion has a point. Your primary charge was security for the Grimmerie, wasn’t it?” said Little Daffy to her husband. “To hear you tel it, the Clock was invented as a wheeled cabinet for safekeeping.

Distraction to the masses on the one hand, a magic vault on the other. No one would fault us if we ditched the scabby thing now. We sure could move ahead faster without it. The book is stil intact.”

“You don’t need me to carry a book,” continued Brrr. “I was a helpful donkey in the shafts of the cart, sure, but I’m not a house pet.”

“Brrr, you do what you like,” said Ilianora to her husband. “It makes no difference to me. You

are

no house pet. Go with Muhlama, or not.”

“I’m not going with her,” said Brrr, though he didn’t know if it was

go with

in the adolescent sense, or

go with

as in the future intentional. And he also didn’t know if he was teling the truth. Ilianora’s suffering charged the conversation with horseradish. If he couldn’t know what his wife felt or meant anymore, how could he understand his own changing aspirations?

“I’l see the girl to the next juncture,” decided Ilianora, “and I’l carry the book that far too. I can’t care for her anymore.” Because caring for Rain would hurt—that much was evident. Too much of the young wounded Nor was stil, after al this time, alive in the elegant veiled adult. Alive and dead at once. Like the dragon, whose wings flopped in the grass as if with spirit, but nothing like the spirit it had once, magicaly, possessed.

Midmorning came, a series of brief squals. Cool, without monsoon steam—glorious. Acorns thrown from trees; the last of some wild plums. Native woodland, nothing magnificent—but at least northern. On the lip of a promontory ahead of them, Muhlama pointed out the arches of some ancient helm that had probably guarded the environs of Restwater from any predation ascending through the Sleeve of Ghastile.

“That’s where you’re headed,” the Ivory Tiger told them. “There’s something of a roof left stil. You can shelter from the rain there, should it come down stronger, and meet your maties. Then my job is done, and I’m off.”

Brrr didn’t comment. He just puled the hobbledy-hoy cart, maybe for the last time. Up a road packed with ancient grey cobbles, a road fringed with drying nettles and slipweed knot. He thought of the toddler’s game, building a church with the fingers of two hands. The guardhouse raised its ribs like the fingers of one of those hands, cupped against the air. Built like that? Or had the fingers of an opposite hand colapsed down the slope years earlier? Yes, he could see ancient slates cladding a shed dependence. He could smel a kitchen fire, a roasting haunch of venison, or maybe loin chops of mountain grite. For a moment when the wind died down he heard the sound of a stringed instrument.

The approach to the ruined keep rose to a point slightly higher than the fingertips of the broken arches. Then the path descended in a gentle S-shaped curve. Muhlama led the way, pacing elegantly, her whiskers twitching to sniff out trouble. But the stiffness in her shoulders relaxed. No danger here apparently except the danger that new circumstance presents to old alegiance. “I’ve done what I said,” she caled.

“Oley oley in-free. Wherever you are, come out, come out. They’re here.”

Brrr was released from his shafts, slipped from buckles and leathers, by the time a low wooden door opened and their hosts emerged. He didn’t recognize the Quadling woman with a domingon in her hands, though he guessed her to be the one caled Candle. He knew Lir, though. Coming behind her, his palms on her shoulders. Lir at thirty or thirty-two, maybe. Fuler in the shoulders, higher in the brow, a great mane of dark hair even a Lion could admire. A habit of youthful quiet and temerity aged into something almost like courage. But what would the Lion know about courage?

“The book,” announced Muhlama, “and the girl who comes with it, as a kind of bonus.”

The humans looked at one another. Curiosity and wariness shaded into something not yet like recognition, not yet like wonder. A mathematicaly perfect pivot, equal amounts of hope on one side and, on the other, alarm that the hope might be unfounded, that this revelation might yet be a mocking lie.

Brrr let them have their human moment. He kissed his good-bye to Muhlama—a final one, a temporary one? He didn’t know. He realized that Ilianora would soon be relieved of responsibility for Rain.

Perhaps her distress would lift, once Rain’s parents took in the fact of their daughter. He wouldn’t abandon Ilianora in any pain, whether he could help that pain or not. If, in time, he couldn’t help it—if, in time, he realized that his not being able to help was making it worse—wel, he would reconsider.

But not yet. For now, he’d stay by her side, through the next round, whatever it might be. Together he and Ilianora, the dwarf and the Munchkinlander, had delivered Rain to her home, or such home as she might hope to have. Rain was safe, or safe enough.

Now Brrr was left to shield the other bruised girl, the stilborn one huddled inside the veiled woman, for as long as he could. If he could. There wasn’t now, nor would there ever be, any shortage of girl children whose safety he would need to worry about, either in or out of Oz.

The Chancel of the Ladyfish

I.

The outlaws had been told by a Swift that Muhlama would be heading a delegation of exiles, but not who would be among them.

Lir gripped his wife by the hand. Hold back this instant longer, Candle. We’ve been waiting for al these years. Don’t scatter her into the clouds, like the little wren she resembles.

She was here. She had come back. (She’d been brought back. She’d been brought in.) There would be time enough to study her. Time had begun again.

He could feel his wife strain to break free, to surround the child with scary, pent-up love. His forearm would be bulging as he staked Candle immobile. Don’t rush the girl.

Our girl.

He tried to advise Candle by the theatrical turn of his own head. Look at Brrr instead. That old Cowardly Lion, as he’d come to be known. There he stands, dropped to al fours like an animal, naked but for a kind of painter’s blue serge smock with a bow at the back. And roling his boulderlike head from the girl to her parents, back and forth. The Lion could look at her. He’d earned the privilege. Lir and Candle would have to wait another moment. Now that there were extra moments.

Brrr had gone silvery about the whiskers. He must be nearing forty, surely? So was it age, exhaustion, or nerves that made the Lion’s left rear leg quiver? His mane was ful and nicely aerated though even his jowls were bejowled. He’d developed not only a paunch but also a bit of an overbite. However, both tokens of age disappeared when the Lion reared to his hind legs. As if he’d suddenly remembered he was a Namory of Royal Oz. He looked ready to curtsey, but he extended his front paw to Lir.

The Cowardly Lion said, “A lifetime or two ago, somebody you may remember as Dorothy Gale once browbeat me to look after you. I paid little attention. Later, a ripe old fiend named Yackle asked me to protect this child if I could. I tolerated her request without imagining I could oblige her. Yet here I am—surprise, surprise. Presenting my consort, Ilianora, and my young friend who goes by the name of Rain.

I’ve unwittingly obeyed both bossy females and done you two services on the same day.” Dropping the sarcasm, he said more huskily, “Would that I could have been of greater service, Lir son of Elphaba.” Lir hooted. “Don’t take

that

tone to me. It sounds like you’ve wandered out of some pantomime about Great Moments of Chivalric Oz. ‘Lir son of Elphaba’? I cal myself Lir Ko now.” Nonetheless, he fel into the Lion’s embrace. The musk of the Lion’s mane was rank; it smeled like young foxes and incontinent humans. “You old pussy,” he murmured. “I never liked you much, and damn it, now I’l be in your debt the rest of my life.”

“A rare thing, for me to have any advantage,” replied Brrr. “I’m sure I’l squander it.” The dwarf nodded in agreement, character assassination at work.

Lir puled back to say, “This is Candle Osqa’ami.” He beckoned his wife forward. She nodded from the waist; but her eyes never left the girl, who was twisting her ragged tresses around her forearm as if in an agony to tear off her own head. A smal greeny-white creature, a ferret or a rotten mink maybe, writhed at the girl’s ankles as a hungry cat might do.

Finaly Lir turned to the woman the Lion had introduced as his consort. Only now was she folding the veil back off her foreheard, puling its drapes away from her cheekbones. The cry Lir gave made everyone start except for Rain, who seemed oblivious.

Nor held up her hand, holding Lir back. “Food first, and water,” said Nor, in a voice that was and wasn’t the voice Lir remembered from childhood. “Our histories have waited this long; they can wait til the washing up. Candle Osqa’ami, show me a chore, and I’l help you with what needs doing. I’m south any appetite for overwrought reunions.” As she passed Lir, she trained her eyes forward, but the fingers of her left hand reached out to graze his elbow and his hip.

Candle didn’t budge, just flapped a hand toward the crumbling narthex as if to let the busybody find whatever she would in there. “We’l folow right along,” said Lir. Nor drifted into the building alone.

Candle dropped to her knees, so Lir dropped too. Candle clapped three times. The girl looked at Candle with mild curiosity, maybe aversion. Candle clapped again, twice, and this time their daughter clapped back. Once. Feebly. It was a start.

“Oziandra Osqa’ami,” said Candle.

“Commonly caled Rain,” remarked the dwarf, to whom no one had been paying attention. “And as we old ones remember from those decades of the Great Drought, Rain rarely comes when she’s caled.

Even when she’s caled by the name she knows. Rain.”

“Oziandra Rain,” said Candle.

“Child,” said Lir. He didn’t know the significance of that Quadling clapping. He just lifted his hands, palms out, as he might to a sniffing hound or a hurt wolf-cub. Safe, open. No stone, no knife.

The dwarf cuffed Rain on the crown of her head. “Go to them, bratling, or we’l never get a bite to eat. After al that poppy-dust in the nostrils I’m stranded on the famished side of peckish.” So Rain stepped forward, out of everyone’s shadows—out of the shadows of the last eight years. And Lir looked at her.