Outcasts (34 page)

Authors: Sarah Stegall

The swish and hiss of the waves echoed him as he knelt. Advancing and retreating with the surge, like dancers at a cotillion, his little paper boats wobbled on the black water. Shelley handed her the light and pushed a small boat further out into the water. She saw that each one held a short stub of candle, a tiny flame shining through the paper. One by one they floated away beyond the circle of lamplight, becoming water-fireflies. The wind had died now, and the only sounds were the splash of dying waves against an occasional rock. Across the water a night bird called and was answered; in a distant house a baby cried (not hers). Above, the scudding clouds parted just long enough for Mary to see some stars, before the window was shut by black clouds.

“What did you dream?” Shelley asked, folding another piece of paper into a boat-shape.

“Graves. My father and mother. A storm.” And you, merging with my father, she did not say.

“Your mother? Ah, a ghost story.” His smile flashed briefly in the dim light. He knelt to place the tiny craft on the water with great care. In his greatcoat with his elbows jutting, he looked like a huddle of sticks. “Were you frightened?”

“Yes, and ⦠no.” She pulled the shawl closer around her shoulders, not for warmth, but as armor, perhaps. “I was at my mother's grave. You were there.”

He smiled up at her. “A sweet memory, surely? For me, sublime.” He stood and took her hands in his. “You changed me, Mary. You changed me forever that day.” He kissed her hair. As always, he recast her memories as their memories.

She stepped back, looking up at him. “You are not my father,” she said.

His blue eyes opened wider. “Indeed, not. Do you want me to be?”

She opened her mouth to say no, and then stopped. Was that not precisely her wish? She saw the dream-man, standing over her mother's graveâShelley/Godwin. Two men merging, becoming the sameâher creator, with herself the figure of her own mother,

the creation of Godwin. For his careful (and careless) tending of her memory had shaped her in Mary's mind as surely as if he had made her with his hands, and she of clay. Mary stared at her lover. “Do you want to be Godwin? Do you want to be my ⦠my father to me? My creator?”

Shelley smiled. “How can that be, when you created me?”

“But I am no maker!” It curled out of her in a wail, a desperate cry born of too much pressure, too many expectations laid on too young a heart. “I am no poet. I am only me, I am not Godwin or my mother. I am not Byron or Polly. I am not even you!”

“No,” he said simply. “You are yourself. To me you are my Maie girl, to William his mother, to Claire a sister. God knows what you are to Albé. You have been all these women and you will be more. But you are, in the end, only yourself.” He thrust his hands into his greatcoat. “You are what you want to be, Mary. That is all and everything that your father taught you. Are you not wise enough, old enough to see that? Wherever you go, whatever you do, you are yourself.” He drew his hand out of his left pocket, frowning down at a crumpled handful of paper.

She stared at him, seeing past him. Something in her wailed in despair, something in her opened wide. Her mouth felt dry. A roaring sound in her ears had nothing to do with the wind sighing through the summer-leafed trees overhead. “Myself ⦔

Shelley looked up from the letter in his hand. Mary recognized her own handwritingâher letter to Godwin, yet unmailed. “I love you, Mary,” her lover said simply. “I will love you forever.” No matter what happens, he did not say, but she heard it nonetheless.

She knew he meant it. She knew he would mean it even if he climbed into another woman's bed. And it didn't matter to her, because suddenly, with a feeling of lightness around her heart, she felt something give way. She was not Godwin's. She was not Shelley's. She was not William's. She was not even her mother's.

“I am ⦠myself.”

“Yes,” he said. He held the letter out to her. “You do not need him.”

He had not broken the seal, but he would know what it said, she was sure. Because he was like that. “I don't need him,” she said. And she remembered the dream-man turning towards her, and the figure in the illustration from her mother's stories, and the future-man with the electric brain that Polidori had spoken of. She remembered the grave of her mother, and her father's near-worship of the dead, his determination to make her into her mother again, to bring back to life in her the dead woman in the ground. Deathâand life again. Willâand passion. Freedomâand responsibility. Wisdomâand utter folly.

We will each write a ghost story â¦

“I'm going back to the house,” she said.

Shelley looked down at the letter, up at her. He didn't ask, and she did not answer, but he smiled. He knelt and retrieved a candle end lying in the sand. He held it to the lamp, caught the flame, and handed the lamp to her. “Mind the path,” he said. “I think it will rain again soon.”

As she walked away, he was folding her letter into a paper boat large enough to hold the flickering candle.

Mary shut the French door behind her, making sure not to lock it. Rain had blown in, and the carpet was damp under her slippers. She trod on something soft.

It was her mother's shawl, lying next to a chair, as if it had slipped off the back. Slowly Mary bent to pick it up. As the light fell on it, she saw that it had been changed. Flowers and vines in green and red and blue meandered from one end of it to the other. Mary instantly recognized her step-sister's handiwork, and clenched the shawl in her fist.

“She had no right,” Mary said. She sank into the chair and spread the shawl out on her lap. Claire had embroidered the pure white expanse of wool with an unruly riot of flowers, meticulously stitched in her fine hand. The shawl now looked nothing like the one that had lain on her mother's shoulders, on hers. It had been transformed, mutilated. As lovely as the work was, to Mary it was a defacement. Hot, silent tears fell on her hands as she turned the shawl around and around in her hands. Could she unpick

the stitches? Yes, but she knew the pinholes would remain, that the wool would forever bear the mark of its wounding. Scars, she thought. Claire has stitched herself into my mother's legacy. She is trying to insinuate her way even there.

Clasping the shawl to her face, she inhaled deeply, but that faint, lingering perfume she associated with her mother, that faint milky smell that was all she had left of the woman who had died to create her, was gone. Now the shawl smelled of Claire's lavender water, deadening the older, dying scents. Mary sobbed into the wool, bereft. Now there was nothing, nothing left of the brave woman who had defied God and man and the Reign of Terror to live her life on her own terms, who had died bringing her into the world.

Nothing left, except herself.

Gradually her sobs subsided and she used the shawl to wipe her eyes. Then she carefully folded the shawl. It was hers no longer. Carefully she laid it on a sideboard and stepped away.

Let Claire have it now. She will need it when the babe arrives.

Mary gathered up the scattered papers and set them under a Sevres bowl on the sideboard. The little writing table sat next to the chimney, now smoldering with the remains of their earlier fire. Her lamp flared across the mirror, momentarily doubling the light in the room. The clock read four and some minutes. She didn't care.

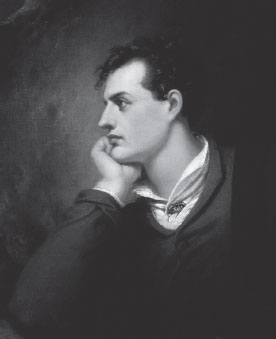

Byron's scrawl covered half a page of ivory paper; under it several more pages peeped out. She swept them aside and set down the lamp. Byron had left the cap off the inkwell; carefully she added new ink and mixed it well. Her hand fairly itched to get to work, but she took her time. When she discovered that the nib on the quill had bent, she made a little sound of frustration. Rummaging in the desk, she found a penknife and carefully trimmed it to a new point. She kept thinking of the portrait of her mother, her father's inspiration, his lost love, dead within weeks of their marriage, forever lost, forever mourned. Godwin had tried to resurrect his beloved wife in their daughter, and failed.

She sat and drew the chair closer. She took a deep breath and dipped the pen in the inkwell. When she drew it out, a drop of blackness hung on the end, quivering. From this drop, she thought, she would write her own Declaration of Independence. From this beginning, a story of love and abandonment, pride and arrogance, of a warm heart betrayed by a cold allegiance.

A story of an outcast, who from a beginning steeped in corruption emerged pure and innocent, like her daughter, like young William. An innocent blighted by lack of love, by cruelty, by rejection from those who should love it.

She drew the edge across the lip of the inkwell, steadied her paper with her left hand, and began at the top of the page:

It was on a dreary night of November that I beheld the accomplishment of my toils.

The pen skritched, dry already. As she lifted it from the page to refill it, she heard Shelley singing, coming up the walk. She glanced out of the window and saw the last of his boats drifting, fading.

As she watched, the last one, made from her letter to her father, was borne away by the waves, lost in darkness and distance.

The End

T

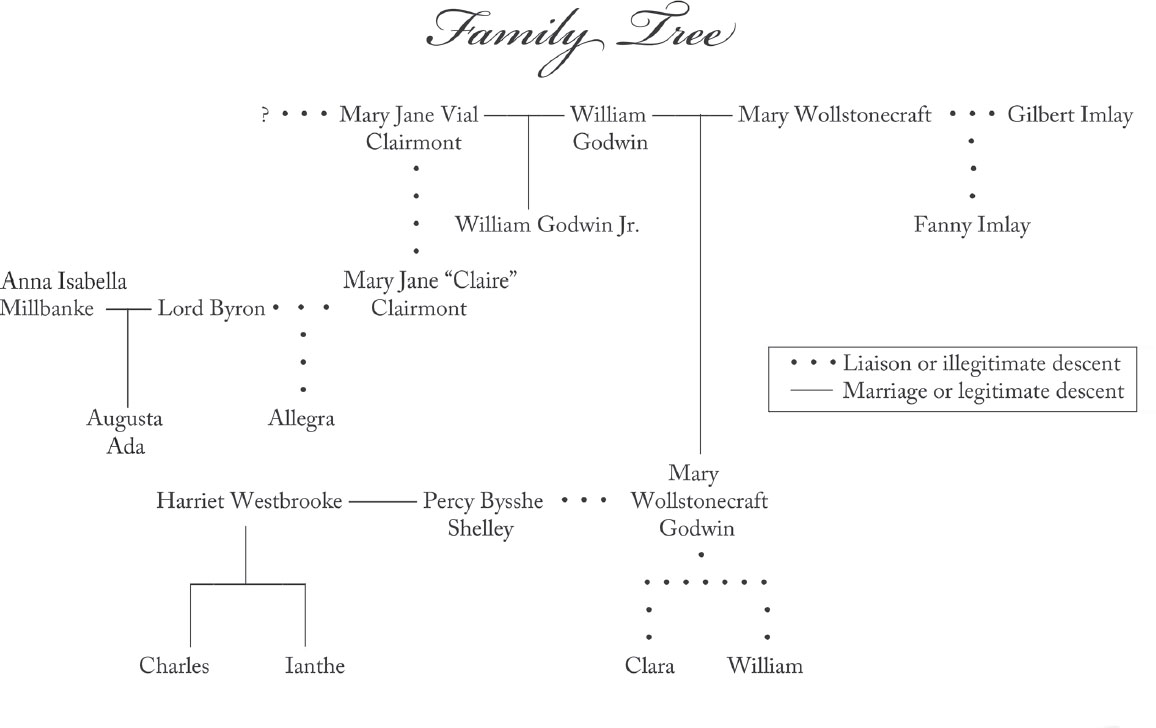

he summer of 1816

was followed rapidly by more tragedy in Mary's life than most women must bear in a lifetime. Within weeks, Fanny Imlay, in despair over her bleak future, committed suicide. A month later, the body of Shelley's wife Harriet, heavily pregnant by another man, was pulled from the River Serpentineâanother suicide. Mary and Percy Shelley married a few weeks later; from that date, Mary never again used her father's surname, and was known for the rest of her life as Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.

On January 13 of 1817, Claire gave birth to a daughter, whom she named Alba, a play on her nickname for Byron, Albé. Byron renamed her Allegra. By then Byron was living in Italy, refusing to see or write to Claire. He had agreed to support his daughter, but on condition that Claire surrender custody to him. Reluctantly, she agreed.

On September 2 of that year, Mary bore a second daughter, named Clara after her first daughter.

In January of 1818,

Frankenstein

was published anonymously. It was an instant sensation, but brought very little money to the cash-strapped Shelleys. In the summer of 1818, one-year-old Clara died in Mary's arms. The following June, the beloved Will-mouse, then three years old, died of malaria in Rome. Mary was pregnant at the time, but for a brief time mourned that she was no longer a mother. The birth of her fourth child, Percy Florence, in November was the only thing that could soften her grief.

In April 1819, John Polidori's expansion of Byron's unfinished attempt at a ghost story was published as

The Vampyre,

the first English novel about vampires, launching a craze for the un-dead at least as enduring as that of

Frankenstein

. But no further success followed, and after struggling with gambling debts and depression, Polidori committed suicide at the age of 25.

Byron placed his daughter in a convent to be raised into a bourgeois young Italian lady. Allegra contracted a fever and died in March of 1822, aged five years. Byron, who had ignored his daughter in life, had her buried with an elaborate inscription. Claire, angry and grief-stricken, spent the rest of her long life (she died in 1879) as a teacher and governess, estranged from Mary and vilifying Byron at every turn.

Shelley's love of boats proved the death of him. In the summer of 1822, returning from a business trip, his boat went down in a storm; Shelley had never taken Byron's advice and learned to swim. His body was not recovered for many days. It was recognized only by the volume of Keats still in his pocket. Byron was present when the body was cremated, by order of the Italian authorities; Shelley's ashes were interred in Rome next to the grave of his son, William. Devastated, Mary returned to England and made her living by writing, as she raised their only surviving child.

Byron now tried to become the Corsair he had written about. Involving himself in various radical political schemes, he undertook an excursion to Greece in an effort to foster revolution. In 1824, in Missolonghi, he died of a fever. Mary saw his funeral cortege pass her small cottage on its way to his interment.

Thus, in less than ten years, the only persons still alive who had been present at the Villa Diodati on that June night of 1816 were Mary and Claire. Mary made her living by writing encyclopedia articles and other work-for-hire, and published more novels. Claire lived most of the rest of her long life alone, in Europe, as a governess and teacher. To the end of their lives, they remained unmarried, on the edges of society, no longer outcasts, but unrepentant advocates of free love, atheism, and republicanism.