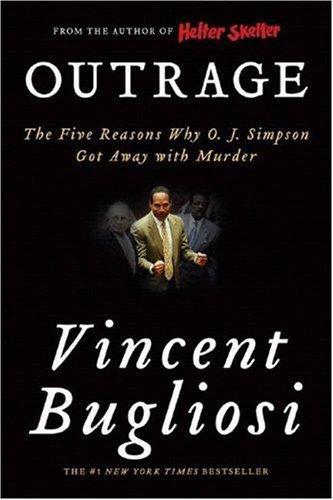

Outrage

TO

THE

MEMORY

OF

NICOLE

BROWN

SIMPSON

AND

RONALD

GOLDMAN

AND

THEIR

SURVIVING

LOVED

ONES

It may be useful to the reader, as background or context for the uncomfortable truths contained in this book, to know why I felt so strongly that Vincent Bugliosi was the only author in America who could write a truly meaningful account of the Simpson murder trial, and why I persisted until I finally persuaded him to write it, if not against his will, at least against his natural inclination.

Vincent Bugliosi should be on any knowledgeable person’s short list of the great lawyers in America, but as a

prosecutor

he stands alone, in a class by himself: His record in the Los Angeles District Attorney’s office speaks for itself: 105 convictions out of 106 felony jury trials; more importantly, 21 murder convictions without a single loss, including the prosecution of Charles Manson in the Tate-LaBianca murder case, which was to be the basis of his true-crime classic,

Helter Skelter

, the book that established him as the most celebrated true-crime author in America.

But perhaps a more substantive measure of Bugliosi’s stature is the judgment of his peers, and here again the weight of evidence is overwhelming. Alan Dershowitz says simply, “Bugliosi is as good a prosecutor as there ever was.” Harry Weiss, a veteran criminal defense attorney who has gone up against Bugliosi in court, makes this comparison: “I’ve seen all the great trial lawyers of the past thirty years and none of them are in Vince’s class.” Robert Tannenbaum, for years the top prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s office, says, “There is only one Vince Bugliosi. He’s the best.” Perhaps most telling of all is the comment by Gerry Spence, who squared off against Bugliosi in a televised, scriptless “docu-trial” of Lee Harvey Oswald, in which the original key witnesses to the Kennedy assassination testified and were cross-examined. After the jury returned a guilty verdict, in Bugliosi’s favor, Spence said, “No other lawyer in America could have done what Vince did in this case.”

The question I asked myself at the outset was this: What would the nation’s foremost prosecutor have done with the evidence in the Trial of the Century? I think you will find the answers in this book as surprising and as compelling as I have. Bear in mind that while Bugliosi’s analysis is unsparing, it is also objective, for he owes nothing to the myth of Simpson’s innocence and has no need, unlike many other writers on this subject, to protect his own tarnished performance in the case.

—Starling Lawrence

W

ell, here I go again. These are the words I am saying to myself after once again (by writing this book) being drawn back into the Simpson case after vigorously trying to remove myself from any association with it for well over a year. The initial shock was indeed overwhelming: to think that O. J. Simpson, famous and admired by millions of Americans, a Heisman Trophy winner who had carried the Olympic torch, could have committed two of the most horrendous murders imaginable…. But once I got past this reaction of disbelief, I found I had very little interest in the case itself. Certainly I was extremely interested in what the verdict was going to be, and if Simpson had testified I would have been interested in the cross-examination of him, but other than that, the case held little fascination for me. The reason is simple. How do you sustain your interest in a case, or in anything, when you already know what happened? And we all know what happened here. Simpson committed these murders. They just played a game during the trial, and I had minimal interest in the game.

The same was true of the Rodney King case. When Stephen Brill, president of Court TV, called me and asked me to commentate the first trial in Simi Valley for Court TV, I declined, telling him I was too busy with other commitments. That was certainly true, but the other reason is that the case held no fascination for me. It was a very important case sociologically, but again, we already know what happened. The crime was captured on film. So too with the Damian Williams case here in Los Angeles during the South-Central riots following the not-guilty Simi Valley verdicts. The crime was captured on film. In the Menendez case, the brothers admitted killing their parents. Where is the mystery? We already know what happened. The only type of criminal case that really appeals to me is a true murder mystery, and the interest is in the mystery, not the murder. But there was no mystery in the Simpson case. Anyone who says this case is a mystery and Simpson might actually be innocent is either being disingenuous—a euphemistic way of saying he or she is lying—or is suffering from a severe intellectual hernia, or is just not aware of the evidence. I know of no fourth option.

Yet many of the media referred to this case as a “true murder mystery.” One writer for a national paper took it a step further and called it “one of the biggest murder mysteries of our time.” The real mystery is how people with IQs no higher than room temperature can write for major publications. But actually, it’s not IQ. It’s a lack of common sense. One thing I have seen over and over again in life is that there is virtually no correlation between intelligence and common sense. IQ doesn’t seem to translate that way.

Other reporters called the case a “classic whodunit,” another way of calling it a mystery. But we all know what a whodunit is. That’s a case where there is evidence pointing to four, five, or six suspects, and the question is, whodunit? But here, not just some of the evidence but all of the evidence pointed to one person and one person only, O. J. Simpson. Not one speck pointed to anyone else. I realize that sometimes in life the truth is an elusive fugitive. That wasn’t the situation with the Simpson case.

Few reporters could resist the observation that the case against Simpson was “based entirely on circumstantial evidence,” the implication being that this was an infirmity. But the reason for this implication is that the reporters, even though it is their job to know better, had no more knowledge of the nature and power of circumstantial evidence than the man on the street. Circumstantial evidence has erroneously come to be associated in the lay mind and vernacular with an anemic case. But nothing could be further from the truth. It depends on what type of circumstantial evidence one is talking about. In a case like the Simpson case, where the prosecution presented physical, scientific evidence connecting Simpson to the crime, it couldn’t be stronger.

The true circumstantial evidence case, and the only kind that is difficult to try, is one in which not only are there no eyewitnesses—only eyewitness testimony; which is notoriously problematic, is direct evidence—but there are no bullet, blood, hair, semen, or skin matchups; in fact, no physical evidence of any kind whatsoever, such as clothing or glasses, connecting the defendant to the crime. That’s the classic, textbook type of circumstantial evidence case, in which you have to put one speck of evidence—an inappropriate remark, a suspicious bank transaction, a subtle effort to deflect the investigation, things like that—upon another speck until ultimately there is a strong mosaic of guilt. But the Simpson case was something entirely different: O. J. Simpson might just as well have gone around with a large sign on his back declaring in bold letters that he had murdered these two poor people. In other words, the case was circumstantial in name only.

Another reason why I sought to remove myself from the case is that I have been trying for some time now to complete my book on the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the most important murder case in American history. Contemporaneously, I was updating my 1991 book,

Drugs in America: The Case for Victory

, which was republished this year as

The Phoenix Solution: Getting Serious About Winning America’s Drug War

. I view the drug problem as the most serious crisis facing our country, and I see this book as my magnum opus. When the media would call for a TV or radio appearance I had a choice: make the appearance, which required the expenditure of several hours out of my day which I didn’t have, or decline, which is never pleasant, but which I did with 95 percent of the requests. Even declining, with any semblance of civility, can take up a lot of time when one is dealing with so many requests, not only from network TV, but from radio stations and newspapers all over the country.

Despite my efforts, I was only partially successful in staying away from the Simpson case. Reporters and talk show hosts are incredibly persistent, and occasionally I would agree to appear on national TV to comment on the Simpson case, every time telling myself it was the last time. But it never was. And since I never do anything, even appear on television, without doing my homework, I kept sufficiently current with the case to know what was going on.

Because I am a writer of true-crime books, during the trial many people suggested to me that I write a book on the case. My invariable response, without giving a second of reflection, was no. The first time I felt the faintest glimmer of interest was when my editor, Starling Lawrence, called me a few weeks after the outrageous verdict and suggested I do a book based on how I would have prosecuted the case, calling it “The Second Trial of O. J. Simpson.” That titillated me somewhat, because I knew the first trial had not been handled properly at all. The problem is that since, among other things, I would have presented much more evidence of guilt than the prosecutors in this case did, I would have had to invent the cross-examination of the witnesses testifying to this evidence, and I had no desire to get into fiction. Also, I was just too busy with my other books to take on a third major book.

But my editor, like the media, was persistent, and he called back a week later to suggest I write not an all-encompassing book on the case, but a book with a narrower focus—why did the prosecution lose this case? The book could be short, he said, almost an informal discussion and “personal conversation” with the reader, an extension of the interviews I’ve given on the case over radio and television, not the in-depth true-crime book I typically write, trying to nail down every date, name, and event with particularity. Because I was just about completing my drug book update, and because I feel very confident I know why this case was lost, I agreed to do the current book.

The reader should know that this book will not be a detailed recitation of all the facts of the case or the testimony and evidence at the trial (although there will be a meaningful amount of both). I assume the reader of this book, if interested enough to buy it, is already reasonably familiar with the case. In terms of heinousness and brutality, on a scale of one to ten, these murders were a ten. A veteran

LAPD

detective, one of the first officers to arrive at the scene, said, “It was the bloodiest crime scene I have ever seen.” Nicole Brown Simpson, in the fetal position, and Ron Goldman, slumped over a few feet away, were found literally lying in a pool of blood, their clothing drenched in blood. The autopsies, conducted on June 14, 1994, showed that Nicole was stabbed seven times in her neck and scalp. The fatal wound was a vicious five-and-a-half-inch slash from left to right across her neck that severed both the left and right carotid arteries, virtually severed the left jugular vein, cut into the right jugular vein, and actually penetrated “for a depth of ¼ inch into the bone of the 3rd cervical vertebra.” The neck wound, the report says, was so severe, “it is gaping [2 ½ inches wide] and exposes the larynx and cervical vertebral column.” Goldman was stabbed thirty times on his scalp, face, neck, chest, abdomen, and left thigh. His fatal wounds were the severing of his “left internal jugular vein” and “stab wounds of the chest and abdomen causing intrathoracic and intra-abdominal hemorrhage.” Many of his wounds were a “combination of stabbing and cutting.” Both victims had defensive wounds to their hands, incurred trying to ward off the deadly assault.

How did it come to pass that someone we know—not believe, but know—committed these two savage murders is now out walking among us, enjoying life with a smile on his face? That’s what this book is all about.

This book sets forth five reasons why the case was lost. But even these five can be distilled down to two: the jury could hardly have been any worse, and neither could the prosecution. In fact, as bad as this jury was, if the prosecution had given an A+ rather than a D© performance (discussed in Chapters 4 and 5 of this book), the verdict most likely would have been different. (Let’s not forget that even with a dreadfully poor prosecution, on the first ballot, which the jury took within an hour after it commenced its deliberations, two of the jurors, a black and a white, voted guilty. If you can get a 10–2 with a D© performance, you can imagine, by extrapolation, what would have happened if there had been an A+ performance by the prosecution in this case, which the people of the state of California were entitled to. I’m very confident this jury would have responded with a guilty verdict, or at an absolute minimum a hung jury.) Even before I saw any of the jurors or heard or read what they had to say, I felt this way. And in listening to the Simpson jurors in posttrial interviews, and reading a book jointly written by three of them, my feelings in this respect have been strengthened. I got no sense at all from them that they didn’t care if Simpson was guilty or not, no sense that their state of mind back in the jury room had been “Even though O.J. is obviously guilty, we like O.J., so let’s give him two free murders,” or “Even though we know O.J. is guilty, blacks have been discriminated against by whites for centuries, so let’s pay back whitey and give O.J. a couple of freebies.” I didn’t sense that, nor do I believe it for one moment.