Pantheon 00 - Age of Godpunk (44 page)

I suspect the people of 2100 will be much richer than we are, consume more energy, have a smaller global population, and enjoy more wilderness than we have today. I don’t think we have to worry about them.

The late – and admirable – Crichton was a far smarter man than I will ever be. His intellectual superiority, especially in matters scientific, means his opinions on climate change and global warming carry considerably greater weight and authority than mine ever will. I’d like to believe his prophecies to be accurate.

I just can’t.

Something in my gut tells me his optimistic outlook is wrong. More than that, any optimistic outlook is wrong. If you ask me, humankind is doomed to a future of rising sea levels, extreme weather events, mass starvation, resource wars, unsustainable mass-migrations from poorer to wealthier nations, animal extinctions, power shortages, and markedly reduced life quality and life expectancy. A hundred years from now I see a global population reduced by two or three billion, almost everyone sheltering from rampant flood waters in quasi-feudal enclaves, surrounded by husks of redundant technology and fighting off invaders with a mix of modern and medieval weaponry. A little bit

Mad Max

, in other words, and a little bit

A Canticle for Liebowitz

.

The stars? Intergalactic colonisation? The outward urge? Sowing the seed of humanity across the cosmos? Not a chance. Such grand visions never come to pass. No one is prepared to pony up the trillions necessary to fund that kind of dream-scale project. No one has the vision. Governments are irredeemably short-termist. They plan five years ahead, if that. This is why I don’t write space opera. To me it isn’t SF, it’s pure fantasy.

Things to come are things to dread. My two sons will grow up in a world where the best is past and where our present era will seem like a golden age – unlimited travel, plentiful food, material affluence, technological superabundance. They will look back on my generation with envious amazement, wondering how we could have been so reckless, so lacking in foresight, so wilfully vandalistic, so damn lucky. And all I’ll be able to do, if I’m still around, is apologise and say we couldn’t help ourselves. We tried but we just couldn’t break the habits of greed and squandering. We recycled our bottles and newspapers, but we knew it was a drop in the ocean. We installed low-energy lightbulbs, but our immense flatscreen TVs made up the difference in electricity consumption. We wanted to go veggie, but the lure of a fat juicy steak was too great.

I was in the dentist’s chair the other day, having a checkup. The dentist enquired about an article I’d written in the paper, prognosticating dire times ahead for planet earth. She told me, with a grim chuckle, that I was about to have a very uncomfortable experience at her hands if I genuinely believed everything was as dark as I’d stated in that piece. She would show her disagreement as only a dentist knows how.

With scenes from

Marathon Man

playing in my head, I desperately racked my brains to recall whether anything I’d submitted to the FT lately matched what she was describing. Maybe some book review where I’d blithely let slip that I reckoned civilisation was screwed? Then, light dawned. There’d been a case of mistaken identity.

“Oh, you mean James Lovelock,” I said. “The great prophet of eco-catastrophe. That’s not me. Definitely not. You can put away your rather enormous drill now. I disagree with everything the man says.”

I don’t, though.

BONUS CONTENT:

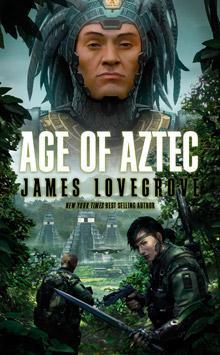

Age of Aztec

Interview

I

N

A

PRIL

2012, with the fourth

Pantheon

book,

Age of Aztec

, hitting the shelves imminently, the

Solaris Books blog

opted to interview James and ask him a few questions about the book. Of course, he also obliged us with his thoughts on gods, writing about them, and which god he’d most like to be, so we thought it would be of interest to our fine readers...

H

E'S WRITTEN ABOUT

an armed uprising against distant but powerful Egyptian divinities, a high-powered slugfest between battle-suited humans and super-heroic Greek gods, and a gritty firefight between an infantry company and an army of ancient Norse giants, but now James Lovegrove - author of the 100,000-selling and

New York Times

best-selling

Pantheon

series, is changing history to take us into a world dominated by an ancient culture...

In bookstores and online now,

Age of Aztec

features a desperate fight by a masked vigilante in a contemporary London dominated by the oppressive and bloodthirsty Aztec Empire.

We asked James about the success of the

Pantheon

series, why he writes, and why he'd love to be an ancient god ...

• Tell us a bit about Age of Aztec and why people should buy it.

With

Age Of Aztec

I wanted to achieve two things. I wanted to write a “dark jungle” novel, very much under the influence of Joseph Conrad, especially

Heart Of Darkness

, and I also wanted to write a story about a masked vigilante – a freedom fighter or a terrorist depending on your viewpoint – one man pitting himself against the system, sort of like a cross between

Batman

and V from

V For Vendetta

. I had very little prior knowledge of the Aztec pantheon before embarking on the book, but what I did know something about was the Aztec empire. They were the hardest and maddest of all the Mesoamerican nations, in thrall to human sacrifice, a brutal, blood-soaked theocratic regime that treated its own people not much better than it treated its enemies. All those hearts being hacked out atop ziggurat temples, plus the Erich Von Däniken-style associations with flying saucers and spacemen gods – who could resist that as the basis for an SF action thriller? The essential counterfactual premise of the novel is that the Aztec empire wasn’t overthrown and eliminated by the Spanish Conquistadors but instead fought back, using technology unknown at the time (the 15th century), and went on to conquer the rest of the world. Now, in the present day, it rules with an iron fist and a very bloody priestly knife, but rebellion is afoot, a resistance both human and otherworldly... And more than that, I shall not say. If potential readers aren’t sold on the strength of that summary, they’d have to be mad.

• With the central premise being worlds where gods are real, how do you keep the format so fresh?

The trick is to approach each

Pantheon

novel as though it’s a completely new thing, an independent entity. I have an innate horror of repeating myself, so I’m obliged by my own inner compulsions to find new ways of tackling the material. What helps is that every ancient pantheon is so different from its peers. I mean, granted, there are often similarities. There’s always a “bad boy” god, for instance, a troublemaker like Set or Loki or Tezcatlipoca, but the overall mythologies vary hugely. That’s something I ruthlessly exploit. As soon as I start the background reading for research, I find the tone, the flavour of the book I’m about to write, and proceed accordingly. The pantheon itself determines the novel that I make out of it – the interrelationships, the exploits, the characters. That’s where the freshness comes from, both from within me, my own ADD-type restlessness, and from outside, the well of pre-existing stories I draw from.

• Are you worried you’re going to run out of gods to focus on?

Not yet. I can think of at least three more pantheons I could use that I haven’t so far, and that’s on top of

Age Of Voodoo

, which I’m currently writing. I certainly have plans for a novel with one of them, and the other two could probably be pressed into service if someone twists my arm hard enough. At some point somebody is going to say, “Enough!” It may be the readers. It may equally be me. In the meantime, though, I’m having too much fun not to carry on.

• Tell us a bit about your writing routine.

It may shock some people to learn that I write first drafts longhand. Each day, I spend the morning scribbling with pen on paper, ensconced on a sofa with my cat curled up next to me and showing his sheer indifference to the creative struggle by being fast asleep and snoring. Come midday, I’ll then sit down at my computer and transfer what’s on paper – usually about 1,000 to 2,000 words – onto the screen, after which I’ll spend some time tinkering and rewriting, installing little bits of research gleaned from the internet, and footling around on email and Facebook and the like. I can’t write directly onto a computer. My brain just isn’t wired that way. I’m of the generation that came before word processors and to me there’s nothing as immediate or “real” as seeing prose come out of the tip of a Parker Rollerball onto rules A4. I like all the crossings-out. I like my appalling handwriting, which is kind of a personal shorthand and which anybody else would find almost impossible to decipher. I liken the process to drawing a comic. You do the pencils, the longhand draft, and then ink them, the transcription onto computer, to make the original art cleaner, smoother and tidier.

• How do you feel about the Pantheon series selling more than 100,000 copies?

After years of critical acclaim and indifferent sales, I’d long resigned myself to being one of those authors whose work is esteemed rather than bought in great quantities. It completely blew me away when I looked over my most recent royalty statements, checked the sales totals, did a little bit of adding-up, and realised the series had hit that milestone. I’d known the books were doing well, but this was a true surprise. A thoroughly pleasant one, I hasten to add. What’s most remarkable to me is how well the novels are doing in the States. I’m something of a parochial writer, and I’ve never cynically courted the American market by writing in an American style with an American setting and an American protagonist, as some authors do, mentioning no names Lee Child. I’m English through and through, and my fiction reflects that. However, Stateside, people seem to “get” the books, and enjoy them, and that’s very gratifying and also exciting. The home audience does too, though, and don’t think I take that for granted.

• What advice would you give to new writers hoping to break into the field?

I’ve been in the business so long now that I can barely remember what it was like to be starting out (he said, stroking his long white beard and taking a puff on his pipe). The main thing is to have talent. Don’t go fooling yourself that you can write when you can’t. Ambition comes next, but it should be tempered with realism. Not everyone in publishing makes as much money out of it as Stephen King or J.K. Rowling. You can’t expect to hit that big, and in fact you shouldn’t expect even to make a living at it. You should do it because you want to and because you feel an overwhelming compulsion to. Always read plenty, imitate but don’t copy your favourite authors, develop your own voice and style, and never, never, never give up, because you can bet there’ll be plenty of setbacks and rejections along the way, and if you let them get the better of you and discourage you, you won’t get anywhere.

• If you were to be one of the gods you’d featured in the Pantheon series, which one would it be?

Ha! I think Quetzalcoatl in

Age Of Aztec

is pretty cool. He’s tough but fair, and tries to do the right thing. Mind you, he slept with his own sister, which is a little bit icky. But aside from that, I wouldn’t mind being him. I’m also pretty fond of Ares in

The Age Of Zeus

, just because he’s proud of who he is, has no illusions about himself, and takes no prisoners. Oh, and Xipe Totec in

Age Of Aztec

, for much the same reasons as Ares.