Paris After the Liberation: 1944 - 1949 (59 page)

Read Paris After the Liberation: 1944 - 1949 Online

Authors: Antony Beevor,Artemis Cooper

Tags: #Europe, #General, #Modern, #20th Century, #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #History

BOOK: Paris After the Liberation: 1944 - 1949

13.28Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

It now seems extraordinary that President de Gaulle and his ministers should have feared that France was again on the brink of civil war. There were also some curiously false echoes of the Liberation twenty-four years before. In an attempt to cow the students, tanks from the 2nd Armoured Division were diverted through Parisian suburbs on what was described as an ‘

itinéraire psychologique

’. *

itinéraire psychologique

’. *

Strikes and rioting eroded government confidence to such a degree over the next two weeks that on 29 May de Gaulle left Paris without even warning his closest colleagues. They arrived at the Élysée Palace just before ten o’clock for a meeting of the Council of Ministers and were aghast to hear that the President had left for an undisclosed destination. Rumours spread rapidly that he had retired to Colombeyles-deux-Églises to announce his resignation. Parisians listened to the contradictory reports on their transistor radios in a state of apprehension comparable with that of the uprising in August 1944, when they feared that the Allies would never reach the city in time. There were even rich

paniquards

– those who could obtain fuel for their cars – taking the road to Switzerland with all their valuables.

paniquards

– those who could obtain fuel for their cars – taking the road to Switzerland with all their valuables.

De Gaulle had in fact flown to Baden-Baden to meet General Massu at the headquarters of the French army in Germany. His son-in-law, General Alain de Boissieu, had arranged the meeting. The President needed a firm guarantee that he had the full support of the army, which had been discontented since his decision in 1962 to withdraw from Algeria. The price was the release from prison of General Salan, whose

putsch

in that year, with paratroopers emplaned at Algiers ready to seize Paris, had collapsed at the last moment.

putsch

in that year, with paratroopers emplaned at Algiers ready to seize Paris, had collapsed at the last moment.

The next morning, 30 May, President de Gaulle reappeared at the Élysée Palace after landing by helicopter at Issy-les-Moulineaux. A communiqué was issued. After a meeting of the Council of Ministers, the President would address the nation by radio. Comparisons were immediately made with his radio appeal from London on 18 June 1940. Gaullist supporters, tipped off that their leader was about to fight back, began to gather in central Paris, armed with tricolours and transistors. The General’s speech at half past four was brief. He was not resigning. He had decided to dissolve the National Assembly and to appoint prefects to take on the post-Liberation authority of Commissaires de la République. But the underlying message of his text was a challenge to the left. If they wanted civil war instead of constitutional government, they would have it. This was de Gaulle’s last dramatic intervention. The next year, following an unfavourable result in a referendum, he resigned as President of the Republic and disappeared to Ireland. The succession was assured with Georges Pompidou as his replacement. The Fifth Republic, with the

dirigiste

Constitution which de Gaulle had wanted in 1945, maintained its stability well beyond the death of its creator eighteen months later.

dirigiste

Constitution which de Gaulle had wanted in 1945, maintained its stability well beyond the death of its creator eighteen months later.

On that afternoon of his radio broadcast, 30 May 1968, the General’s supporters gathered exultantly on the Place de la Concorde and the Champs-Élysées. ‘De Gaulle is not alone!’ they cried. Fromcrowds nearly a million strong, there emerged a variety of other slogans. The favourite was the chant ‘

Le communisme ne passera pas!

’ No doubt there were many present who had been supporters of Marshal Pétain; but the vast majority now regarded themselves as average Frenchmen, exasperated with political strikes and chaos in the Latin Quarter. The Sartrian road to freedomwas at an end. Radical ideas had failed to overcome the bourgeoisie.

Le communisme ne passera pas!

’ No doubt there were many present who had been supporters of Marshal Pétain; but the vast majority now regarded themselves as average Frenchmen, exasperated with political strikes and chaos in the Latin Quarter. The Sartrian road to freedomwas at an end. Radical ideas had failed to overcome the bourgeoisie.

The Gaulish leaders in league against Julius Caesar (100–44 BC), led by Vercingetorix (d. 46 BC), from a protective sleeve for school books, late nineteenth century.

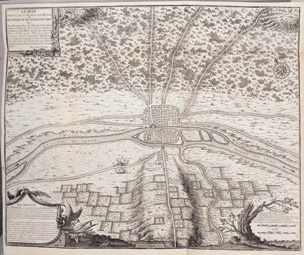

Lutetia or the second plan of Paris in the fourth and fifth centuries AD, French School, 1722.

Sainte Geneviève gardant ses moutons

, French School, sixteenth century.

, French School, sixteenth century.

The Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Paris.

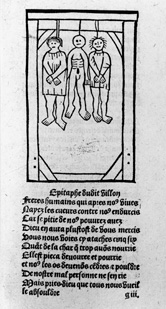

Epitaph of François Villon (1431–?) from

Le Grant Testament Villon et le petit, son codicille. Le jargon et ses balades

, 1489.

Le Grant Testament Villon et le petit, son codicille. Le jargon et ses balades

, 1489.

‘Weighing of Souls’, French fifteenth-century stone carving.

Engraving of the

danse macabre

, artist unknown, 1493.

danse macabre

, artist unknown, 1493.

Portrait of Catherine de Médicis (1519–89), French School, sixteenth century.

Engraving of ‘La Cour des Miracles’.

Other books

Ensayo sobre la lucidez by José Saramago

Kill Me by White, Stephen

Stripped Down by Lorelei James

The Unexpected Coincidence by Amelia Price

Put Me Back Together by Lola Rooney

The Fallen One (Sons of the Dark Mother, Book One) by Lenore Wolfe

Brightness Falls by Jay McInerney

Misterioso by Arne Dahl, Tiina Nunnally

Critical Mass by David Hagberg

The Arabian Nights (New Deluxe Edition) by Muhsin Mahdi