Paris Times Eight

PARIS TIMES EIGHT

Deirdre Kelly

GREYSTONE BOOKS

GREYSTONE BOOKS

D&M PUBLISHERS INC.

VANCOUVER/TORONTO/BERKELEY

Copyright ©

2009

by Deirdre Kelly

09 10 11 12 13 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright license, visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to

1

-

800

-

893

-

5777

.

Greystone Books

An imprint of D&M Publishers Inc.

2323

Quebec Street, Suite

201

Vancouver

BC

Canada

V5T 4S7

www.greystonebooks.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kelly, Deirdre,

1960

â

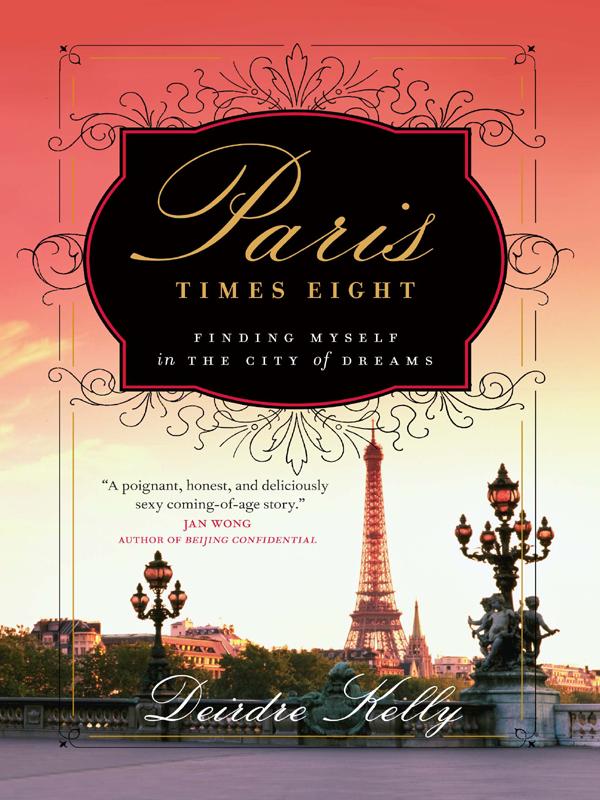

Paris times eight : finding myself in the City of Dreams / Deirdre Kelly.

ISBN 978-1-55365-268-7

1.

Kelly, Deirdre,

1960

â.

2.

Paris (France)âSocial life and customs.

3.

Paris (France)âBiography.

4.

JournalistsâCanadaâBiography.

I. Title.

DC705.K44A3 2009Â Â Â 070.92Â Â Â C2009-903861-7

Editing by Susan Folkins

Copyediting by Eve Rickert

Cover and text design by Ingrid Paulson

Cover illustration © Terra Standard/Free Agents Limited/

CORBIS

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on paper that comes from sustainable

forests managed under the Forest Stewardship Council

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, the Province of British Columbia through the Book Publishing Tax Credit, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (

BPIDP

) for our publishing activities.

To my mother, who said,

Because I know you can . . .

CONTENTS

I WOULD LIKE

to thank Susan Walker, recently dance writer for

The Toronto Star,

and Carol Toller, a trusted editor and steadfast colleague at

The Globe and Mail.

Both read early versions of the manuscript, and their constructive criticism and enthusiasm helped guide me forward at the beginning.

Cameron Tolton, my former professor at the University of Toronto, served, as he has selflessly done for the last thirty years, as mentor and confidant, even going as far as to confirm that I was right in wanting to celebrate the enduring allure of Paris when he offered at the Royal Ontario Museum a miniseries of public lectures on Paris films.

A heartfelt thank-you also to Salah Bachir, president of Cineplex Media, whose longtime friendship and generosity of spirit helped see me through much of the writing process, Jeffrey Sack, the lawyer who took my case at

The

Globe and Mail;

Dr. Vera Victoria Madison for her invaluable advice; and Arline Malakian, Franco Mirabelli and Jackie Gideon for their eager support of the project.

My gratitude also to my agent, Hilary McMahon of Westwood Creative Artists, who tirelessly encouraged me. And to Bruce Westwood, a committed Francophile who said writing well is the best revenge.

Thanks also to Jennifer Barclay and Amy Logan Holmes, who published my first exploration of Paris as a literary subject in their jointly edited book,

AWOL

.

Rob Sanders and Nancy Flight of Greystone Books were the biggest supporters of this book. They never stopped believing in me, even when I didn't, and gave me all the time and hand-holding I needed to get it completed.

They were also responsible for introducing me to Susan Folkins, a gifted editor whose expert eye and highly attuned ear helped give the book a heightened clarity and shape. I thank her for all her hard work and passion. The next

kir'

s on me!

Thanks also to my younger brother, Kevin Kelly, who played audience to my first stories when we were small. And to my mother-in-law, Desanka Barac, for always wanting to lend a hand.

Finally, thank-you to my husband, Victor Barac, who listened and empathized and suggested and nodded in all the right places. He is my beacon, the one who showed me that one true journey is the journey of love. To him I give thanks also for our two beautiful children, Vladimir and Isadora Barac. The perfection of them, their precious sweetness, inspired me to want to create something everlasting. Something to make them proud.

“LIFE IS A

process of becoming, a combination of states we have to go through. Where people fail is that they wish to elect a state and remain in it. This is a kind of death.” I cupped my palm around these words in hopes that my mother, sitting next to me in the car, hands hawkishly grasping the wheel, would not see what was making me open my eyes in wonder. I didn't have to worry. Her mind was on her driving, or rather speedingâwe had less than five hours to make it to Montreal, and we were racing against the eastbound Highway

401

traffic.

My mother isn't what you would call a bookish person. She doesn't entirely respect books and has never understood my passion for them. “You've always got your nose stuck in some book,” she would say. Or, “Stop reading so much and go outside. You're pasty-faced.” Or, “You think everything's in a book? Get real.”

But books were my salvation, an escape from my family, which included a runaway father, a volatile mother, a wayward brother, an emotionally vacant maternal grandmother, and a grandfather who, my mother alleges, molested his own children, including her, while drunk. Not exactly a fairy tale, unless we're talking the Brothers Grimm. I found kindred spirits in books. They were the one place where my mother couldn't intrude and where I could escape my loneliness and sadness, forget my hurts, conceal my fears, and rise above my shame.

Nowâironically, with my mother as chauffeurâI was physically in flight. It was the summer of

1979

. I had just graduated from high school, and to mark the end of what seemed an interminable childhood, I was departing Canada for Paris for my first visit there, at the invitation of Jenna and Nigel,

*

a Canadian couple who had asked me to help look after their two young boys. I was anticipating a reprieve from all that tormented meâmy mother's complicated love and my own deeply sorrowful self. But the book in my hand, Anaïs Nin's study of D.H. Lawrence, was making the break difficult.

Nin's unhappy family life made me think of my own. My mother was always in the driver's seat. But though she might be driving, I was fiercely driven, determined to define myself in opposition to a person who was always telling me I was just like herâa chip off the old block. This notion mortified me.

When I was growing up, my mother wore hot pants and orange fishnet stockings, walked with a wiggle in her step should we go to a restaurant with one of her paying boyfriends, and ordered frosty mint-green grasshopper cocktails with paper umbrellas. She was a hot tamale. Men wanted her, I knew. She often told me that the husbands of her girlfriends would hit on her and that she would have to put them in their place. I didn't want to know this, but she said she had no one else to tell. And so I understood her to be a sex kitten but not a floozy. Still, seeing my mother in any kind of sexual light nauseated me. I couldn't articulate it at the time, but I wanted a mother who was nurturing, not naughty. A mother who was present, there for me, instead of the other way around.

She wore her streaked brown hair short now, with a chunk of bangs falling over one eye like Natalie Wood's (her favorite actress since she was young and saw

Marjorie

Morningstar

). She cut it herself, often with a razor blade, slashing away at the back of her neck to correct what some idiot hairdresser had done. No one ever got it right with her. She had hazel eyes that she frequently narrowed to a piercing glare, and a prominent Presbyterian nose that, as she might say, was frequently out of joint. She wore too many gold rings at a time, one, sometimes two, to a finger, even though her hands weren't her best feature. She picked at them, tearing at the skin around the nails until it was raw. I never knew her to wear nail polish or eye shadow or perfume. Lipstick she liked, shades called Chiffon and Pearl Praline. The colors complemented her fair, flawless complexion, making her beautiful in her own way, I thought as I watched her hunched at the wheel, driving with her chest practically thrust upon the steering wheelâlike a battering ram wheeling down the highway.

Partly she drove that way because of her height. She was five-foot-three to my five-foot-six and couldn't see out the window without propping herself up. But it was also a style of physical combativeness that she had perfected over the years. She was a jock, a field hockey player to be precise, whose bellicose ways with a stick had enabled her to hold her own.

Her bald independence and aggressive behavior had given her alpha-female ways some harsh masculine coloring. Even on the highway she was not exactly acting like a lady. “Get the hell outta my way!” she screamed at a driver in front of her. “Goddamn man! Did you see that?”