Parting the Waters (162 page)

Read Parting the Waters Online

Authors: Taylor Branch

A messenger interrupted one of the marathon debates in Hattiesburg with news that Louis Allen had been found under his logging truck in Amite County, dead of three shotgun wounds to the head. Guilt ate at Moses even before he found the stricken widow. He had been out of touch. It had been more than a year since his last letter to John Doar, after a deputy sheriff had broken Allen's jaw with a flashlight: “They are after him in Amite⦔ Allen had been a marked man ever since telling Moses he had seen the state legislator shoot Herbert Lee in cold blood. The potshots and threats had so frightened him that Louis Allen had tried repeatedly to leave the state, once saying “Thank you, Jesus” when he crossed the line into Louisiana, but he simply did not have the wherewithal to live outside Mississippi. Lost away from his family and his logging work, Allen had returned to a series of half-finished escape plans, including one that fell through when his mother got sick and died in his last week. Moses knew none of this last pathos, but he did realize that he had failed to reach Camus' ideal of being neither a victim nor an executioner. He was both, and he was also a political leader in spite of his obsession for consensus. He had led Louis Allen to where he was now, and it would make utterly no difference unless he led others.

Moses returned straight to Hattiesburg. “We can't protect our own people,” he said bluntly. With that he threw his influence and reputation behind an expanded plan to bring at least a thousand Northern volunteers to Mississippi in the summer of 1964.

Â

Back home after the Kennedy funeral, King felt the wide range of his life's journey. He had to cancel the SCLC's credit cards because Abernathy and others were spending too much and the treasury was bare again. Robert Kennedy dismissed his objections to the Albany Nine prosecutions in a terse letter. From Selma, Mrs. Boynton asked him to help in the desperate case of forty elderly Negro women who had been locked out of a rest home for protesting when one of them was beaten in the registration line; Boynton wanted to buy a sewing machine so that some of the women could earn their keep in private homes. King mediated a dispute over a dentist bill for Mahalia Jackson, made more speeches, and sat alone with President Johnson for an hour in the close embrace of noble dreams as big as Texas. Back home, sick in bed, he received the first white graduate student pursuing a doctorate on King's oratory. The children were running wild through the house. “I think we're gonna have to let Dexter go out,” King said. “He doesn't have the restraint, uh, the virtue of quietnessâ¦I'll call mama downstairs.” When the student asked about the effects of Kennedy's death, King said it was a blessing for civil rights. “Because I'm convinced that had he lived, there would have been continual delays, and attempts to evade it at every point, and water it down at every point,” he said, almost brightly. “But I think his memory and the fact that he stood up for this civil rights bill will cause many people to see the necessity for working passionatelyâ¦So I do think we have some very hopeful days ahead.”

The reaction to Kennedy's assassination pushed deep enough and wide enough in the high ground of political emotion to enable the movement to institutionalize its major gains before receding. Legal segregation was doomed. Negroes no longer were invisible, nor those of normal capacity viewed as statistical freaks. In this sense, Kennedy's murder marked the arrival of the freedom surge, just as King's own death four years hence marked its demise. New interior worlds were opened, along with a means of understanding freedom movements all over the globe. King was swelling. Race had taught him hard lessons about the greater witness of sacrifice than truth, but there was more. Nonviolence had come over him for a purpose that far transcended segregation. It touched evils beyond color and addressed needs more human than status or possessions. Having lifted him up among rulers, it would drive him back down to die among garbage workers in Memphis. King had crossed over as a patriarch like Moses into a land less bounded by race. To keep going, he became a pillar of fire.

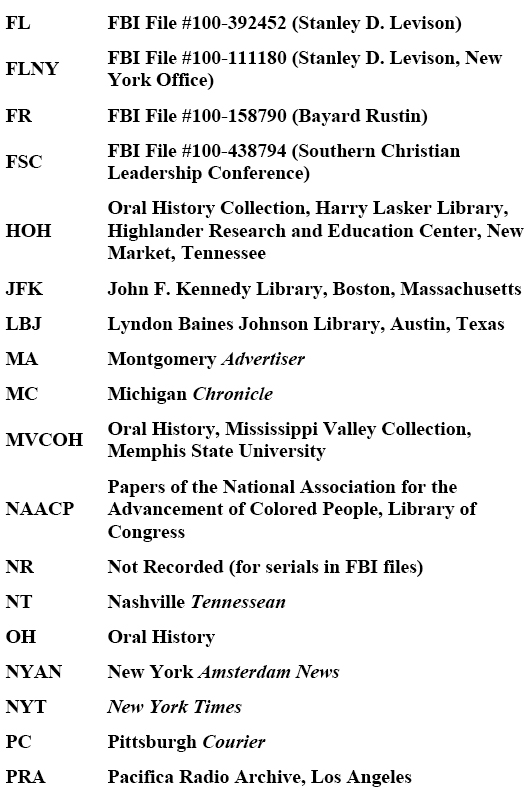

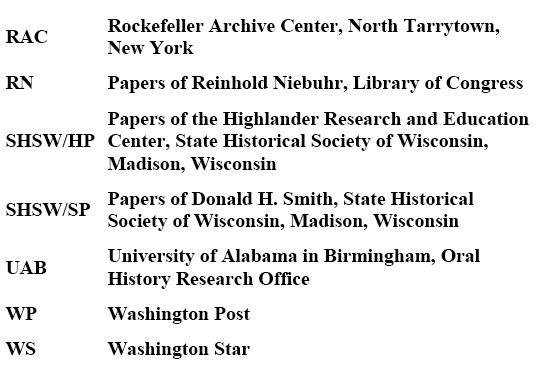

I am grateful to Alan Morrison of the Public Citizen Litigation Group and to the lead counsel in my case, Katherine Meyer, for patient, skillful pursuit of classified FBI material on Stanley Levison.

My editor, Alice Mayhew, has lifted me through this, our third book together, with her sustaining belief in the project. I thank her, along with at least a few of the people at Simon and Schuster who I know have gone beyond professional duty to help me: Henry Ferris, George Hodgman, Tina Jordan, David Shipley, Marcia Peterson, Eileen Caughlin, Natalie Goldstein, and Lisa Petrusky. Richard Snyder and other executives have financed me generously (but not extravagantly) for more than six years, beyond expectations of commercial return. I thank the John S. Guggenheim Foundation for a grant that subsidized the better part of one year's research. As always, I am grateful to my agent, George Diskant of Los Angeles, for his diligent encouragement of our family's welfare.

Our seven-year-old daughter Macy and five-year-old son Franklin have only gently inquired what their father has been doing upstairs all their lives. My heart's response to them, to Christy, and to other family members belongs privately elsewhere, but I do want to acknowledge the advice, encouragement, and inspiration of a few special friends: Scott Armstrong, Samuel Bonds, Karen De Young, David Eaton, Mary Macy, Bettyjean Murphy, Dan and Becky Okrent, Charles Peters, John and Susan Rothchild, Michele Slung, and Nicholas von Hoffman.

Among the employees of the libraries and archives cited in the notes, I am especially indebted to the following people, some of whom have since moved on to other positions: Louise Cook, Cynthia Lewis, and Diane Ware of the King Archives in Atlanta; Howard Gotlieb of the Mugar Library at Boston University; Martin Teasley of the Eisenhower Library in Abilene; Will Johnson and Ron Whealan of the Kennedy Library in Boston; Linda Hanson and Nancy Smith of the Johnson Library in Austin; Elinor Sinnette and Maricia Bracey from the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University; Harold Miller of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin in Madison; Sue Thrasher and Paul DeLeon of the Highlander Research and Education Center in New Market, Tennessee; James H. Hutson of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress; Joyce Lee of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a division of the New York City Public Library; Joseph Ernst of the Rockefeller Archive Center in Pocantico, New York; Walter Naegle of the A. Philip Randolph Institute in New York; Emil Moschella and Helen Ann Near of the FBI's Records Management Division; Janet Blizzard, James P. Turner, Nelson Hermilla, Curtis Goffe, and William B. Jones of the U. S. Department of Justice; Nancy Angelo of the Pacifica Radio Archive in Los Angeles; and Marvin Whiting and Donald Veasey of the Birmingham Public Library. I am grateful to Archie E. Allen, Edwin Guthman, C. B. King, and Mrs. W. E. “Pinkie” Shortridge for sharing historical materials in their personal possession. Jennifer Bard and Beth Taylor Muskat ably conducted specialized research during 1983.

This book would not have been possible without the cooperation of several hundred people who agreed to share with me their personal knowledge. Their names are scattered throughout the notes. Some, like Ella Baker, Septima Clark, C. B. King, E. D. Nixon, and Bayard Rustin, have since died. Some remain new friends, and I respect others for persisting in our interviews through pain or disagreement. Of those who responded to several inquiries over the years, I owe special thanks to Ralph Abernathy, Harry Belafonte, James Bevel, G. Murray Branch, John Doar, Clarence Jones, Thomas Kilgore, Bernard Lee, Beatrice Levison, Burke Marshall, Robert P. Moses, Kenneth Lee Smith, Harry Wachtel, and Wyatt Tee Walker.

Similarly, I want to pay special tribute to those writers whose work opened new regions of pleasure and investigation to me, for which I am grateful beyond the literal debts cited in the notes: Clayborne Carson, W. E. B. Du Bois, Samuel Gandy, David Garrow, Thomas Gentile, Richard Kluger, Leon Litwack, Walter Lord, Aldon Morris, Pat Watters, Carter G. Woodson, and Lamont Yeakey.

One

FORERUNNER: VERNON JOHNS

outdoor sheriff's sales: E. King.

Great South

, p. 333.

more dignified access: Int. Dr. Zelia Evans, June 8, 1983.

property worth $300,000: Evans,

Dexter Avenue

, p. 14.

“on American soil”: Du Bois,

Souls

, p. 216.

largest Negro church: Int. Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, March 5, 1984.

proceeds to the church: Int. William Beasley, secretary, First Baptist Church, Dec. 20, 1983.

exchange for the property: Ibid.

“Brick-a-Day Church”: Ibid.; program for the Centennial Celebration of the First Baptist Church, Montgomery, 1967.

firmly unrepentant: Int. R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983.

“God-blessed”: Evans,

Dexter Avenue

, p. 62. Trail information, int. R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983.

in October 1948: Dexter's official history states that Johns took up the pastorate in 1947, but all the Johns relatives cited below agree that Vernon Johns moved to Montgomery in October 1948, four months after his wife and two months before the rest of his family.

the stuff of legend: Sources used below on Vernon Johns generally include Gandy,

Human

, and Boddie,

God's Bad

. On Johns's family background, sources include interviews with the following relatives: Robert Johns (brother), Jan. 11, 1984; Vernon Increase Johns (son), Feb. 14, 1984; Altona Johns Anderson (daughter), Jan. 31, 1984 and Feb. 7, 1984; Enid Johns (daughter), Jan. 24, 1984 and Jan. 30, 1984; Jeanne Johns Adkins (daughter), Jan. 28, 1984; William Trent (wife's brother), Feb. 2, 1984; and Barbara Johns Powell (niece), Dec. 9, 1983. On Johns as a preacher, sources include interviews with Dr. Samuel Gandy, Oct. 19, 1983; Rev. S. S. Seay, Sr., Dec. 20, 1983; Rev. G. Murray Branch, June 7, 1983; Rev. Gardner Taylor, Oct. 25, 1983; Rev. Charles S. Morris, Feb. 3, 1984; Rev. Thomas Kilgore, Nov. 8, 1983; Rev. Vernon Dobson, Oct. 5, 1983 and Dec. 2, 1983; Rev. James L. Moore, Dec. 2, 1983; Dr. E. Evans Crawford, May 31, 1983; Rev. Melvin Watson, Feb. 25, 1983; Rev. David Briddell, Aug. 17, 1983; and Rev. Marcus G. Wood, Oct. 4, 1983. On Vernon Johns in Montgomery, sources include interviews with William Beasley, Dec. 20, 1983; Dr. Zelia Evans, June 8, 1983; Jo Ann Robinson, Nov. 14, 1983; Rufus Lewis, June 8, 1983; E. D. Nixon, Dec. 29, 1983; Richmond Smiley, Dec. 28, 1983; and R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983 and Feb. 16, 1984. Also specific sources as cited below.

with a scythe: Yeakey, “Montgomery,” p. 110. Also int. Altona Johns Anderson, Jan. 31, 1984, and Jeanne Johns Adkins to author, Feb. 5, 1984.

white man named Price: The Price story was repeated to the author in only slightly different forms by all the close relatives of Vernon Johns who gave interviews.

“like she was a white woman”: Int. Vernon Increase Johns, Feb. 14, 1984.

every word from memory: Gandy,

Human

, p. xvi.

“or students with brains”: Ibid., p. xvii. Also int. Rev. G. Murray Branch, June 7, 1983, and Rev. Charles S. Morris, Feb. 3, 1984.

the University of Chicago: Gandy,

Human

, p. xix, and Jeanne Johns Adkins to author, Feb. 5, 1984. The Oberlin stories are repeated in generally the same fashion by the scattered Johns sources cited above.

“some mountain-top experience”: Gandy,

Human

, p. 51.

who married Thurman: Int. Rev. Vernon Dobson, Dec. 2. 1983.

selling subscriptions: Int. Rev. Charles S. Morris, Feb. 3, 1984. Morris traveled with Johns for five summers, 1936-40.

and a semi-fresh shirt: Int. Dr. Samuel Gandy, Oct. 19, 1983.

to change the Dexter hymnal: Int. Enid Johns, Jan. 24, 1984.

He beckoned Edna King: Int. R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983.

“not a dry eye”: Int. Rev. James L. Moore, Dec. 2, 1983.

“spinksterinkdum Negroes”: Int. Altona Johns Anderson, Feb. 7, 1984.

“hesitation pitch”: Tygiel,

Baseball's

, p. 227.

executive order of July 26: Donovan,

Conflict

, p. 411.

silken cords that never broke: Int. William McDonald, Dec. 29, 1983.

“Selma needs the water”: Ibid.

one case against a storekeeper: Int. E. D. Nixon, Dec. 29, 1983. Nixon says he went to Tuskegee with Johns and the victim.

against six white policemen: Int. Altona Johns Anderson, Feb. 7, 1984. Anderson says she went to Tuskegee with Johns and the victim.

“should know better”: Int. Richmond Smiley, Dec. 28, 1983.

“hell of a funeral”: Int. Rufus Lewis, June 8, 1983.

“semi-annual visit to the church”: Int. R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983, and many others, as this remark to the august Trenholm was widely heard and seldom forgotten.

“murderer in the house”: Int. Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy, March 5, 1984. The Adair murder story was mentioned by many other Johns sources.

one dentist and three doctors: Yeakey, “Montgomery,” p. 17.

“important business activity”: Gandy,

Human

, p. xv.

“some land he owns”: Boddie,

God's Bad

, p. 65.

it “cheapened” the church: Int. Jo Ann Robinson, Nov. 14, 1983.

kept playing the Bach: Int. Enid Johns, Jan. 24, 1984, and Barbara Johns Powell, Dec. 9, 1983.

“weren't bought in the store”: Int. Richmond Smiley, Dec. 28, 1983.

“when Negroes start making them”: Int. Rev. James L. Moore, Dec. 2, 1983.

arrange a truce: For the deacons' meeting over the fish generally, int. R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983, and Rev. Vernon Dobson, Oct. 5, 1983.

them with his fists: Int. Rev. G. Murray Branch, June 8, 1983, and R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983.

“all out of here!”: B. Smith,

They Closed

, p. 38. This book treats the Prince Edward County school strike and its aftermath. The same subject is covered in Kluger,

Simple Justice

, pp. 451ff.

comic book between her knees: Int. Barbara Johns Powell, Dec. 9, 1983.

“limb is not a man”: Kluger,

Simple Justice

, p. 478.

still had no telephones: Int. Barbara Johns Powell, Dec. 9, 1983.

so plainly “tickled”: Int. Robert Johns, Jan. 11, 1984.

quoting all that poetry: Ibid.

her astonishing achievement: Int. Barbara Johns Powell, Dec. 9, 1983.

to anyone in Montgomery: Ibid.

“each other's names!”: Int. Dr. Zelia Evans, June 8, 1983.

$1.95 from a white woman: Jeremiah Reeves case. Discussed in King speech of April 6, 1958, BUK 1f11a.

with a tire iron: Int. Enid Johns, Jan. 24, 1984.

“Safe to Murder Negroes”: Int. Altona Johns, Jan. 31, 1984. See also Yeakey, “Montgomery,” pp. 104ff, Gandy,

Human

, p. xv, and B. Smith,

They Closed

, p. 78. This incident is one of the most popular of the Johns stories and was mentioned to the author by practically every source who knew him.

“his hide is not worth it”: B. Smith,

They Closed

, p. 78, and int. Barbara Johns Powell, Dec. 8, 1983.

Sherman's memoirs and “When the Rapist Is White”: Int. Altona Johns Anderson, Feb. 7, 1984.

women of the church were incensed: Int. Rev. G. Murray Branch, June 8, 1983, and R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983.

this latest resignation, his fifth: Int. R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983.

fault she shared with her uncle: Int. Barbara Johns Powell, Dec. 9, 1983.

to meet Martin Luther King, Jr.: Int. R. D. Nesbitt, Dec. 29, 1983 and Feb. 16, 1984. Also Nesbitt, A/OH.

Two

ROCKEFELLER AND EBENEZER

first gift: Read,

Spelman

, pp. 64-65.

“Paddle My Own Canoe” and “Pleased Although I'm Sad”: Flynn,

God's Gold

, pp. 53, 110.

never bring reproach: Read,

Spelman

, p. 83.

awarded its first three in 1897: Brawley,

Morehouse

, p. 83.

October 29, 1899: E. Smith, “Ebenezer.”

threatening foreclosure: Ibid., p. 1. Also King Sr.,

Daddy

, p. 84.

Ebenezer was prosperous: Ebenezer bought the Fifth Baptist Church on Bell Street, pursuant to resolution by Fifth Baptist, on Dec. 12, 1900. Fulton County Deed Book 152, p. 76.

Ricca & Son: Last Will and Testament of Alberta Williams King, City of Atlanta Estate #97282, Will Book 109. p. 37.

“supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon”: Andrew Sledd, “The Negro: Another View,”

Atlantic Monthly

, July 1902.

“did not reflect”: NYT, Oct. 20, 1901, p. 1.

“wise and just to civilize”: NYT, Oct, 27, 1901, p. 11.

Atlanta race riot: AC, Sept. 21-25, 1906. See also Golden,

Mr. Kennedy

, p. 48.

president of the Atlanta: E. Smith, “Ebenezer,” p. 3. Also King Sr.,

Daddy

, in the introduction by Benjamin S. Mays.

shyness and humility: King Sr.,

Daddy

, p. 21. (In this autobiography, Daddy King describes his wife's education and social position in some detail, but says little about her character or appearance.) Also int. Rev. Larry Williams, Dec. 27, 1983.

would not be noticed: Mrs. Leathers (local public librarian), April 1, 1970, A/OH.

“kind of fearful”: Int. Rev. Joel King (Alberta Williams' brother-in-law), Jan. 9, 1984.

doctorate upon him in 1914: E. Smith, “Ebenezer,” p. 3.

children in the flames: Hugh Davis Graham and Ted Robert Gurr,

Violence in America: Historical and Comparative Perspectives. A Staff Report to the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence

, Vol. I, p. 254.

in Ohio to bury her: Flynn,

God's Gold

, p.464.

another $50 million: Ibid., p. 443.

completed by 1918: Read,

Spelman

, p. 194.

“Well, I'se preaching”: King Sr.,

Daddy

, p. 21.

a used Model T Ford: Ibid., p. 60. King says his mother traded one cow for the Ford, but this is unlikely given the relative values of cows and cars about 1918. Unless Mrs. King owned a truly amazing beast, she would have had to swap at least three or four cows for a Model T that would run.

whom he had never met: Ibid., pp. 13â15.

“father wouldn't allow it”: Ibid., p. 69.

asked her to court: Ibid.

attended Morehouse only: Ibid., p. 75.

“just not college material”: Ibid., p. 76.

bearer to classes: Ibid.

Robert E. Lee: Read,

Spelman

, p. 204.

Buddha, Lao-Tze: Harry Emerson Fosdick, “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” as reprinted in

Christian Century

, June 28, 1922, p. 713.

John Foster Dulles represented Fosdick: Hoopes,

The Devil

, p. 8.

“Jesse James of the theological world”: Fosdick,

The Living

, p. 153.

“Crowds Tie Up Traffic”: NYT, Oct. 27, 1924.

“like your frankness”: Fosdick,

The Living

, pp. 177â78.

razed the apartment buildings: See NYT, Jan. 29, 1926.

On October 5, 1930: NYT, Oct. 6, 1930, p. 11. On Rockefeller and Fosdick, see also Ahlstrom,

Religious History

, p. 911.

of a heart attack: King Sr.,

Daddy

, p. 90.

“I am the First Lady”: Ibid., p. 92.

feelings of his wife: Ibid., pp. 92â93. King twice mentions the sentiment against him among the Ebenezer deacons.

padlock on the church's front door: Ibid., p. 93.

about my father's

BUSINESS

: As discussed in Ahlstrom,

Religious History

, p. 905.

no credit in the ledger: E. Smith, “Ebenezer,” p. 5. Daddy King's methods and innovations also discussed in int. Rev. G. Murray Branch, June 7, 1983, Rev. Gardner Taylor, Oct. 25, 1983, Rev. Thomas Kilgore, Nov, 8, 1983, and Rev. Marcus G. Wood, Oct. 4, 1983, among others.

one nickel for Atlanta Life: Int. Rev. Thomas Kilgore, Nov. 8, 1983. Kilgore first went to Ebenezer and to the King home in 1931, just before King took over the church. He recalls that Ebenezer members still were talking with approval about how Mrs. Williams was holding herself in the background for the sake of her daughter. In later years, as a nationally prominent minister himself and colleague of King Jr., Kilgore often discussed Daddy King's genius as a church financier at preachers' gatherings.