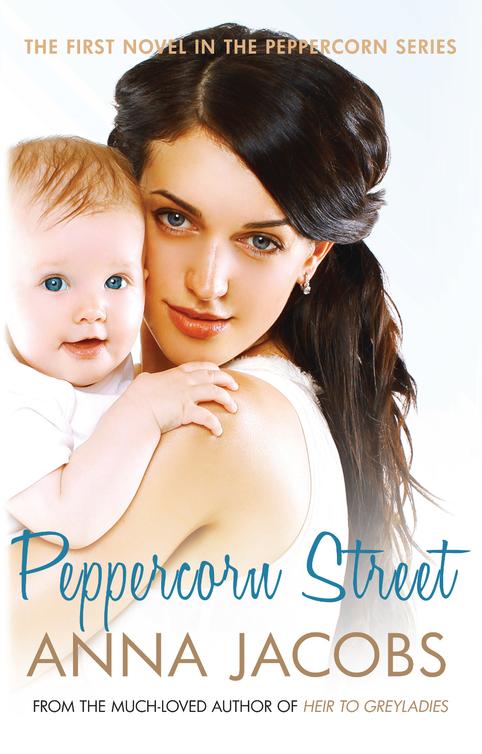

Peppercorn Street

Authors: Anna Jacobs

A

NNA

J

ACOBS

- Title Page

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-One

- Chapter Twenty-Two

- Chapter Twenty-Three

- About the Author

- By Anna Jacobs

- Copyright

Wiltshire, Sexton Bassett

Janey Dobson heaved the buggy up the stairs while her social worker carried little Millie up to the first floor for her, opening the door with a smile and a flourish.

‘Here we are, as far away from Swindon as we can place you and still keep you in our district. I think you’re going to like this flat. It’s been newly refurbished.’

Taking her wailing daughter into her arms, knowing she had no choice but to live here, Janey walked inside and turned round slowly on the spot, studying her new home.

The main room was bigger than she’d expected, with pale cream walls – new paint, too, from the smell. To her relief the bedroom she and Millie would share, though smallish, was completely separate. The kitchen was in a recessed corner at the back, consisting of a sink, a small gas cooker and a fridge, barricaded by about a metre and a half of freestanding bench top with cupboards underneath.

She breathed a sigh of relief. She’d been wondering how to afford a fridge. ‘Thanks, Pam. This’ll be great.’

‘It’d be better if it was on the ground floor, but the other five flats are either occupied or assigned.’

‘I don’t mind. It’s a huge improvement on the last place.’

‘You’ve got Millie to thank for that. She cried so often the owners insisted we get you out of there. Grotty B&Bs like that one are only supposed to be used for emergency accommodation, but we’re so short of places to put people they’re nearly always full.

‘Now, fasten Millie into the buggy and we’ll bring up the rest of your stuff. The people from

Just Girls

will be delivering a cot this afternoon and a few other things to help you set up home.’

Janey helped bring in her meagre possessions, together with some bits and pieces Pam had given her today. Who’d have thought she’d be a mother and have her own home at this age?

Or that her parents would throw her out for keeping Millie.

She still hadn’t got her head round their rejecting her and their granddaughter. People complained about the social services, but they’d been wonderful to her when she’d fallen through their local office doors, weeping and desperate, literally on the street with only a small suitcase. ‘Thanks for all your help, Pam.’

‘My pleasure. Look, let me show you how the heating works and then I’ll have to dash. I’ll pop round to see you next week but if there’s any problem, get straight back to me. And be sure to register at the medical centre I showed you. They have an excellent child health clinic.’

‘I will.’

When she was alone, Janey went to sit on the sagging armchair, rocking the buggy to and fro, enjoying the quietness. She’d lived in lodgings until the birth, working at two or three odd jobs, washing up in a café, anything. When she’d started having her baby, she’d packed her bags and said goodbye to her landlady, a dour woman who wouldn’t have her back with a baby.

No one except the social worker had visited her in hospital and she’d been glad to move to the

Just Girls

hostel afterwards. The matron there had helped her learn to look after her baby, but she was only allowed to stay for three months, hence the B&B and at last this place.

‘We’ll be all right here, Millie darling,’ she said, but her voice wobbled. She’d never felt so alone in her whole life. No matter how kind social workers were, you were just a job to them, and even that was better than no one in the world caring whether you lived or died.

She was responsible for a child’s life and everything else that went with that, but she still felt as if she was playing at being a grown-up.

Unstrapping Millie, she spread out a blanket on the floor so that her four-month-old daughter could kick, then went to investigate the kitchen. The cupboards were full of dust and odd screws or bits of wood from the installation and the fridge was new – and totally empty. She switched it on and put in her few bits of food.

Millie seemed happy so Janey quickly washed out the cupboards, then made a cup of tea while she waited for the shelves and drawers to dry. When the baby grew hungry,

she prepared a bottle of formula. There was never any trouble getting Millie to drink her bottles, thank goodness. She was such a good baby.

Afterwards Millie fell asleep very suddenly, which made things a lot easier. Janey put her back on the floor and covered her with a blanket. Poor little love! She had a bright red patch on one cheek still which meant more teeth were coming through. She had the two upper front teeth already.

Janey tiptoed across to deal with the bedroom. There was enough room for a cot as well as the single bed, thank goodness. She pulled a face at the old-fashioned wardrobe against one wall, a huge thing with a mirror on the door and shelves inside it on the left. Since the baby was still asleep, she unpacked their clothes. Even combined, their things looked lost in that gigantic wardrobe.

She studied herself in the mirror. She’d grown her hair because it was cheaper and could just be tied back. It was a nondescript mid-brown but she couldn’t afford streaks. Luckily she’d lost all the extra pregnancy weight and could get into her normal clothes again. Pam had persuaded her mother to hand those over one day when her father was out. He’d have refused just to spite her.

And she was learning a lot about charity shops, where you could find all sorts of things if you took the time to search.

If only her parents had let her have her computer! She could have played around on it even if she couldn’t afford an Internet connection.

Someone rang the doorbell and as she went to use the

crackly intercom for the first time, Millie woke with a start.

‘Is that you, Janey? Dawn here from

Just Girls

. We’ve brought you a cot and a few other things.’

‘Brilliant. I’m pressing the release button for the front door. I’m on the right on the first floor.’ She picked her daughter up and shushed her gently, then went to open the door.

She knew Dawn, who had visited the hostel a few times, but not the other woman who was helping carry up the pieces of an old-fashioned cot.

Dawn looked round. ‘Not bad at all. You should see some of the places where our girls have to live. We’ll just fetch the rest then we’ll help you set up the cot. Oh, this is Margaret, by the way.’

They brought up all sorts of bits and pieces, three loads in all. ‘You never know what you need,’ Dawn said cheerfully. ‘If you find you don’t need any of these, bring them back to our shop. You can’t miss it. It’s on High Street. One person’s rubbish is another person’s treasure. Some of the other girls go there on Tuesday afternoons for a cup of coffee and a natter. Now you’re living in Sexton Bassett, why don’t you join us? Do you think you could make it tomorrow?’

‘Not tomorrow, no. I’ll be too busy settling in here, shopping and catching up with the washing.’ And she desperately needed some peace and quiet to get her head round what she would do with her life now.

‘Well, don’t forget to come next week. Since you’re new to town, it’ll help you to meet a few people.’

‘I know. I won’t forget.’

Janey was near tears by the time they’d shown her

everything they’d brought, even a bundle of rags for cleaning, something she’d never have thought of. But she’d learnt not to give in to her emotions. Well, she didn’t give in as easily as she used to, anyway. ‘Thank you. I can’t tell you how grateful I am. Um – is there a library near here?’

‘Go down to High Street and turn right. It’s about a five minute walk on this side.’ Dawn fumbled in her bag and produced a piece of card, scribbling on it. ‘Here, give them this. You’ve no way of proving you live here yet, but they’ll take my word for it that you’re bona fide and let you join.’

‘Thank you.’ The tears welled up again but Janey blinked hard, refusing to let them loose.

As they got ready to leave Dawn asked gently, ‘Are you sure you’ll be all right, dear?’

‘Yes. Yes, I’ll be fine. I’m really grateful for all your help.’

But of course she wept after they’d left because one of them had given her a calendar. As she turned it to February and hung it up on a nail in the kitchen, today’s date seemed to jump out at her and she started to sob. She’d hoped her mother would at least send her birthday wishes, because she had Pam’s contact details, but she hadn’t. Her father never bothered about birthdays, but her mother had usually managed to conjure up some small treats.

She was glad she’d told Pam not to give them her new address, though she hadn’t explained the real reason for that: she was terrified of a certain person getting hold of it.

Well, she was eighteen now, whether anyone acknowledged it with a card or not, officially an adult – and still crying like a child. That had to stop.

Surely things would get better now?

Winifred Parfitt walked slowly up Peppercorn Street, glad of her father’s old silver-headed walking stick these days. The houses at the lower end had all been converted into flats now, with ugly dormer extensions poking up to make full use of the attic space. No one cared two hoots whether the houses looked attractive, only how much money could be wrung out of a property.

Pausing for breath near a newly renovated house, she watched a woman with grey hair carry a baby inside and behind her a pretty young woman hauled one of those funny three-wheeled pushchairs up the steps. What did they call them? Buggies?

The girl didn’t look old enough to have a baby. Children grew up too quickly these days, encouraged to act like women before they’d finished school even.

Just past this huddle of mass dwellings near High Street were more flats, but these were of better quality, older houses converted with an eye to street appeal. She sighed, remembering when this was the best street in the small town of Sexton Bassett. These houses had had gardens filled with flowers and lush shrubs in those days, not expanses of black tarmac with white lines painted on it.

Halfway up the sloping street Winifred stopped for another rest, because her shopping bag was heavy. She looked at the new group of retirement villas, finished only

last month. The developer had made a little cul-de-sac off Peppercorn Street and called it Sunset Close. Of course! Everything was ‘sunset’ as far as old people were concerned. She got sick of the sound of that word.

The gardens of the villas were tiny and bare as yet. Well, no use putting plants in at this time of year. She sighed, remembering the huge old house that used to stand here and the lad who’d lived in it, a lad who’d asked her father’s permission to come courting just before he went into the air force. Jack had been killed in the final year of the Second World War and she’d never found another young man to match him. She still kept his photo beside her bed. He looked so proud in his brand-new uniform. She was probably the only one who remembered him now. He’d been an only child. They’d planned to have four children. Now she had none.

A developer had wanted to demolish the old house a few years ago but had found it hard to get permission because it was heritage listed. Then one night last year it had burnt down. End of problem. There were now nine bungalows on the plot of land.

Over 55s only, the adverts had said. Her nephew had suggested she buy one and sell her home for development. Bradley had mentioned it several times and she was getting irritated by this. Why couldn’t he understand that she loved the house she’d lived in all her life, however inconvenient and old-fashioned it was?

Lately Bradley had grown impatient with her, going on and on about how she wasn’t thinking clearly.

Was she losing her grip? He hadn’t said that openly, but she’d made one or two mistakes which he’d pounced on.

No, they had just been mix-ups. Mentally she was as acute as she’d always been. She could still do a crossword quickly and accurately, and answered most of the questions on quiz shows on the television, except for those about pop music and sport, of course.

She started walking again. The houses nearer to hers were semi-detached, Edwardian residences with large rooms and high ceilings. Most of them had been tastefully refurbished, she’d give the newcomers that, but these people didn’t make good neighbours. They were so busy chasing money and ferrying their children around, they didn’t have time to do more than nod at her. She missed having real neighbours to talk to or share a cup of tea with.

She missed having friends, too. Hers had died one by one over the past five years. So sad. The funeral of the final one had been yesterday and she’d been the only mourner because poor Molly had been a spinster like her. There were a lot of unmarried women in her generation, thanks to Hitler and Mussolini. After the war there simply hadn’t been enough men left to go round.

Molly’s lawyer had asked Winifred to make an appointment to see him about a bequest, but he lived at the other end of town, so she’d have to take a taxi. More expense. If Molly had left her the books and bookcases, as she’d once promised to do, they’d be very welcome. You couldn’t have too many books. They didn’t die on you. She’d make an appointment in a day or two.

She paused at her gate, a little out of breath, and frowned as she looked at the garden. She really ought to get someone in to do the front. Gardening was far too

much for her these days. But share values had tumbled and with them her income, so she simply couldn’t afford it and that was that. The best she could manage now was to hoe the weeds along the path.

With a sigh, she pushed open the gate, closed it carefully and walked to the front door. It was dim inside because she kept the front curtains drawn for privacy. She shivered. The front of the house wasn’t much warmer than outside. She’d be glad when spring arrived. Even if she’d been able to afford to have full central heating installed, she didn’t have the money to run it.

Hanging her coat up carefully on the hallstand she went through into the kitchen and servants’ quarters. She spent most of her time in here now in winter, because her nephew had found her a small oil-fired Aga

second-hand

a couple of years ago. He’d said it wasn’t good for the house to get damp in the winter. It wasn’t good for her, either, but he didn’t seem to care about that. She was beginning to wonder about where Bradley’s real interest lay: her or the house she’d foolishly told him he’d inherit one day.