Pericles of Athens (31 page)

Read Pericles of Athens Online

Authors: Janet Lloyd and Paul Cartledge Vincent Azoulay

As Pauline Schmitt Pantel has shown, that polemical interpretation deserves radical

revision. With the creation of the

misthos

, Pericles was not establishing a new form of patronage—community patronage—to take

over from private patronage, which Cimon embodied, as is clear for two reasons. In

the first place, the

misthos

was not distributed by any identifiable individual, but by the community itself.

So its assignation created no personal dependence between donor and recipient. Instead,

it was the community that redistributed to a particular fraction of itself (the judges)

wealth that it considered them to deserve. Second, its aim was radically different

from that of private patronage: far from being a form of assistance, as was claimed

by the detractors of radical democracy, this payment was awarded for active participation

in the city institutions and so in no sense had an infantilizing effect.

28

Instead of being a measure reminiscent of the Roman client-system, the introduction

of the first

misthoi

diminished the influence that members of the Athenian elite could acquire through

patronage. However, it never quite ousted the latter phenomenon, if only on account

of the size of the sum of money paid, which was relatively small, certainly not enough

to satisfy the needs of the poorest citizens.

29

However that may be, the payments did not turn Pericles into the unchallenged patron

of the Athenian community.

By now, at the end of our investigation, that supposed Periclean monarchy seems no

more than a myth. The great construction works and the establishment of the

misthos

testify to the growing sovereignty of the

dēmos

just as much as to the domination of the

stratēgos

. Not only was Pericles obliged constantly to work with the other magistrates, but,

both institutionally and socially, he was placed under the strict control of the Athenian

people.

P

ERICLES UNDER

C

ONTROL

: T

HE

P

OWER OF THE

E

NTIRE

C

OMMUNITY

!

One of Many Magistrates

Pericles never held military power on his own. The

stratēgoi

always acted in a collegial fashion, never individually:

30

a single magistrate could never impose his will upon his colleagues, unless, that

is, they wished him to do so.

So his influence has probably been overestimated, partly as a result of the point

of view adopted by the literary sources and the context in which they were produced.

The comic writers based their craft on personal attacks and always set particular

individuals on stage, often enough exaggerating their influence the better subsequently

to demolish them. It was as if one were to pass judgment on the British political

scene, gauging it solely in relation to the TV series

Spitting Image

, a satirical puppet show. As for Plutarch, his biographical viewpoint inevitably

focused excessively on his particular hero, and it did so the more emphatically given

that he was writing within a political framework—the Roman Empire—in which personal

power had become the norm.

31

An attentive rereading of the texts suggests that we should adopt a more circumspect

attitude. Although Thucydides is always quick to ascribe unequaled domination to Pericles,

he also mentions plenty of other important actors in the period between 450 and 440,

32

at both the military and the diplomatic levels. First, at the military level it is

the

stratēgos

Leocrates who is in command in the war against the people of Aegina in the early

450s (1.105.2); Myronides distinguished himself at Megara (1.105.3), as did the spirited

Tolmides both at Chalcis and against the Sicyonians in 456/5 (1.108.5), before suffering

a bitter defeat at Coronea in Boeotia in around 447 (1.113.2). In the years between

440 and 430, the

stratēgos

Hagnon seems to have held all the key roles. He was

stratēgos

alongside Pericles in the second year of the campaign against Samos (440–439),

33

and was then, in 437/6,

34

sent to found the colony of Amphipolis in Thrace, which was a great honor for him.

In fact, Hagnon was judged by the Athenian people to be sufficiently powerful to deserve

ostracism,

35

although, in the event, not enough votes favored his banishment. Second, at the diplomatic

level, Pericles clearly remained in the background—whether or not deliberately is

not known—in the negotiations with the Spartans. The Thirty Years’ Peace was negotiated

by Callias, Chares, and Andocides in 446, and Pericles was not even present at the

negotiations.

36

Similarly, at the time when the plague was ravaging the city and the Athenians sent

ambassadors to parley with the Spartans (Thucydides, 2.59), this was clearly against

the advice of the

stratēgos

.

37

It is true that the posthumous aura of Pericles eclipsed many actors of the time,

but they too shaped the destiny of the Athenian city in the course of those troubled

decades. Throughout his career, the

stratēgos

inevitably had to share power, as was the custom in Athens, and above all had to

submit to popular control. In the final analysis, it was the people who remained sovereign.

However persuasive Pericles may have been, his influence was only temporary and could

at any point be challenged by a change of heart on the

part of the

dēmos

. As there were no political parties in Athens, nor any stable majority, every decision

was the subject of negotiation between the orator and the people. The balance was

precarious, and the situation of orators was often uncomfortable, for the popular

assembly could change its mind and sometimes did so very rapidly, retracting its earlier

commitments. Not long after Pericles’ death, Thucydides mentions two successive assemblies,

the second of which reversed the decisions made a few days earlier on the fate of

the Mytilenaeans who had revolted in 427 B.C. Even an orator with a huge majority

of votes in favor of his advice on one day could find himself totally rejected on

the next.

38

In a wider sense too, the people exercised strict control over the orators and

stratēgoi

, maintaining them in a perpetual state of tension by resorting to more or less formalized

supervision.

Multiform Institutional Supervision

In Athens, the

stratēgoi

and, more generally, all incumbents of magistracies were submitted to frequent and

persnickety controls. These checks involved, in the first place, a rendering of accounts

at the end of a magistrate’s mandate, necessitating a double examination. In the fourth

century—and probably as early as the fifth—

stratēgoi

had to face a commission of controller-magistrates, the

logistai

, who verified all financial aspects of their management. In cases of proven irregularities

the

logistai

, who were selected by lot from among all the citizens, could refer the affair to

the courts. Furthermore, the

stratēgoi

could be prosecuted by any citizen before the members of yet another committee, an

offshoot of the council. These were the

euthunoi

. If they judged the complaint to be well founded, they passed the case on to the

competent magistrates (

thesmothetai

), who then organized a trial.

39

Historians have for many years maintained that, in cases where a

stratēgos

was reelected, this procedure was omitted for practical reasons—for instance, the

magistrates might be on a mission far from the city, rendering the examination impossible.

In that case, Pericles would not have had to render any accounts during the fourteen

years in which he had, without fail, been reelected; and this would have greatly diminished

the control exercised over him. But in reality this hypothesis has to be abandoned.

In the first place, expeditions of long duration were rare in the fifth century; Pericles

was never away from Athens for more than a year, except at the time of the war against

Samos, which lasted from 441 to 439. Second, Pericles did render his accounts after

the Euboean revolt, in 447/6, despite the fact that he was reelected as

stratēgos

for the following year. “When Pericles, in

rendering his accounts for this campaign, recorded an expenditure of ten talents as

‘for sundry needs,’ the people approved it without officious meddling and without

even investigating the mystery” (Plutarch,

Pericles

, 23.1). So it is clear that

stratēgoi

did render their accounts even when they were reappointed to their posts.

40

One anecdote recounted by Plutarch conveys just how stressful the procedure was for

Athenian magistrates, even the most influential of them: “[Alcibiades] once wished

to see Pericles and went to his house. But he was told that Pericles could not see

him; he was studying how to render his accounts to the Athenians. “Were it not better

for him,” said Alcibiades, as he went away, “to study how not to render his accounts

to the Athenians?” (

Alcibiades

, 7.2). Alcibiades was Pericles’ evil genius, but this remarkable role-reversal turns

the undisciplined youth’s tutor, Pericles, now no longer Alcibiades’ teacher, into

his pupil in the school of crime!

Over and above that exercise of control, at the end of a magistrate’s duties, the

Athenians had the power to depose the city’s principal magistrates even while they

were still carrying out their official mandate: each month the Athenians voted, with

a show of hands, on whether or not they confirmed their magistrates in their positions,

epikheirotonia tōn arkhōn

.

41

In the event of a negative vote (

apokheirotonia

), the magistrate was forthwith deposed. This was probably the procedure of which

Pericles was a victim in 430/429, when he was dismissed from his duties as a

stratēgos

.

42

Following that first sanction, the

stratēgoi

could be arraigned for high treason (

eisangelia

). Treason was a fairly vague notion to the Athenians; losing a battle or being suspected

of corruption was sometimes enough to set the procedure in motion. Pericles himself

probably suffered this bitter experience in 430/429, when, after being deposed, he

was judged and sentenced to pay a very large fine.

43

According to Ephorus, the source for Diodorus Siculus,

44

his accusers blamed him for being corrupt, and this probably explains why Thucydides,

in contrast, goes to such pains to emphasize the incorruptibility of Pericles in his

final panegyric for the

stratēgos

(2.65.8).

Last, the Athenians also had at their disposal a more general mode of control over

members of the city’s elite: the procedure of ostracism. This was instituted following

Cleisthenes’ reforms; it consisted of exiling for a period of time any figure considered

to wield too much influence. This limited the risks of a return to tyranny. The decision

did not need to be justified—a fact that many ancient authors considered to be scandalous.

It was applied for the first time in 488/7 B.C. against a certain Hipparchus, son

of Charmus, who was probably related to the family of the former tyrants of Athens.

In 485 B.C., Pericles’ father was a victim of the procedure of ostracism, but he

was recalled at the time of the Persian Wars. According to Plutarch, it was because

Pericles feared that he, in his turn, might be ostracized that he sided with the

dēmos

. Ostracism thus constituted a permanent threat that hung over the heads of the most

influential Athenians and encouraged them to conform to popular expectations.

Ostracism, which was voted upon every year, took place in two stages. In the sixth

month of the year, a preliminary vote that took the form of a show of hands decided

whether or not to initiate the procedure. If this was in principle accepted, a second

(secret) vote took place to decide who was to be condemned. This vote was conducted

using potsherds (

ostraka

) upon which the citizens wrote the name of the man they wished to ostracize—a process

that provides a good indication of the relative literacy of Athenian society. The

individual with the most votes was then exiled, provided that a

quorum

of at least 6,000 voters had taken part. Those graffiti did not always stop at naming

a victim but in some cases also mentioned the reasons that motivated the vote. It

sometimes happened that the sexual reputation or even sexual behavior of men involved

in politics was invoked to justify their exile. While some were blamed for their excessive

wealth—such as one “horse breeder”—others were accused of adultery (

moikhos

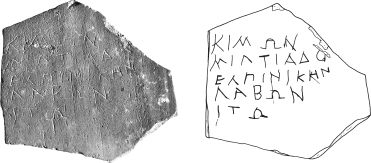

). As for Cimon, Pericles’ first opponent, on one of the ostracism shards bearing

his name (

figure 9

), he was even accused of maintaining an incestuous relationship with his sister,

Elpinike: “Cimon [son of] Miltiades, get out of here and take Elpinike with you!”

45

Because a vote of ostracism did not need to be justified by any particular offence

that was penally reprehensible, it rested partly on the accusations laid against politicians

for their personal behavior.

46

FIGURE 9.

Ostraka

of Cimon (ca. 462 B.C.). From S. Brenne, 1994, “

Ostraka

and the Process of

Ostrakophoria

,” in W.D.E. Coulson et al., eds.,

The Archaeology of Athens and Attica under Democracy

. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books, 13–24, here fig. 3-4, p. 14.