Persian Fire (46 page)

Leonidas it was who took the perilous commission. As representative of the senior royal line, he would have felt that it was his duty to do so, no doubt — but he may have had a more personal motive, too. The ghosts of the murdered Persian ambassadors were not, perhaps, the only phantoms abroad that summer in Lacedaemon. More than a decade had passed now since Cleomenes, his legs and stomach fretted by a carving knife, had been found twisted in the stocks. What remained mysterious was whether he had perished by his own hand — just punishment for his oracle-bribing, god-baiting impiety — or had been the victim of a brutal conspiracy, one possibly orchestrated by the Spartan high command itself. Either way, Leonidas must have felt himself implicated in his predecessor's horrific end. Cleomenes had been his own kin, after all. The blood had long since been scrubbed away, but the sense of a curse, oppressive, menacing, as close as the August heat, still lowered over Sparta. Leonidas, preparing for his desperate mission, would hardly have forgotten the menacing terms of the oracle: either his city was to be wiped out 'or everyone within the borders of Lacedaemon, Must mourn the death of a king, sprung from the line of Heracles'. It would surely not have escaped his attention either that it was on a peak above Thermopylae that Heracles himself had perished, consigning his mortal flesh and blood to fire that he might then ascend to join the gods. Well, then, might Leonidas have dismissed the Hippeis, that crack squad of three hundred young men who customarily served in battle as the bodyguard of the king, and replaced them with older veterans — 'all men with living sons'.

79

A ringing statement of intent. Whatever might happen at the pass — whether glorious victory or total defeat — Leonidas would stay true to his fateful mission. One way or another, he would secure the redemption of his city. There was to be no retreat from Thermopylae.

Hipparchus, the playboy tyrant whose murder in a lovers' tiff back in 514

bc

had been commemorated by the Athenians as a blow struck for liberty, had himself, throughout his reign, always delighted in invention. An ardent patron of architecture, as princes so often are, he had also possessed a rare passion for literature. Travellers could still read, inscribed beneath the erect phalluses that were a somewhat startling feature of way-markers in Attica, pithy and improving verses, composed by the murdered Pisistratid himself. In other ways, too, the Athenians had benefited from Hipparchus' bookish brand of tyranny. It was thanks to his enthusiastic backing, for instance, that the cream of Greek literary talent, who would once have sniffed at Athens as a backwater, had come to regard the city as a cultural powerhouse, and flocked to settle there. So determined had the tyrant been to ferry celebrity poets to his court that he had even laid on a luxury taxi service for them, in the form of a fifty-oared private galley.

Even more than for modern literature, however, Hipparchus' true enthusiasm — and it was one shared throughout the whole Greek world — had been for two peerless epics:

The Iliad

and

The Odyssey,

composed centuries previously, and set during the time of the Trojan War. Little was known for certain of their author, a poet named Homer — but he was, to the Greeks, so infinite, so inexhaustible, so utterly the well-spring of their profoundest presumptions and ideals, that only the Ocean, which encompassed and watered all the world, was felt to represent him adequately. No wonder that Hipparchus, looking to put his city on the literary map, had been keen to brand Homer — who was generally, and frustratingly, agreed to have been a native of the eastern Aegean — as somehow Athenian. Pisistratus, Hipparchus' father, when he sponsored an edition of the poet, was even said to have tried slipping a few surreptitious verses of his own into the texts, hymning Athens and her ancient heroes; Hipparchus himself, less vulgarly, had introduced recitals from the epics to the Panathenaea. Not that these were performed in any refined spirit of

belle-lettrisme,

however, being rather, like the athletic contests that also featured in the festival, ferociously competitive —which was only fitting. 'Always be the bravest. Always be the best.' Maxims, it went without saying, from

The Iliad

itself.

And regarded by Greeks everywhere, despite Hipparchus' best efforts, as the birthright of them all. The Spartans, for instance, those countrymen of Helen and Menelaus, hardly needed to stage poetry readings in order to parade their affinity with the values of Homer's epics. If the letter of their military code derived from Lycurgus, then its spirit, that heroic determination to prefer death and 'a glorious reputation that will never die',

1

to a life of cowardice and shame, appeared vivid with the fearsome radiance of the heroes sung by the 'Poet'. And of one hero more than any other: Achilles, greatest and deadliest of fighters, who had travelled to Troy, there to blaze in a glow of terrible splendour, knowing that all his fame would serve only to doom him before his time. True, the pure ecstasy of his glory-hunting, which had led him to squabble with Agamemnon over a slave-girl, sulk in his tent while his comrades were being slaughtered, and return to the fray only because his beloved cousin had been cut down, was a self-indulgence that could hardly be permitted a Spartan soldier. Nevertheless, that death in battle might be beautiful, that it might enshrine a warrior's memory, even as his spirit gibbered in the grey shadows of the underworld, with a brilliant and golden halo, that it might win him

'kleos',

immortal fame: these notions, forever associated with Achilles, were regarded by the Greeks as having long been distinctively Spartan, too. Others might aspire to such ideals but only in Sparta were citizens raised to be true to them from birth.

When Leonidas, leading his small holding force, arrived in early August at the pass of Thermopylae, then, the example of the heroes who had fought centuries previously in the first great clash between Europe and Asia could hardly have failed to gleam in his mind's eye. From Homer, he knew that the gods, 'like birds of carrion, like vultures', would soon be casting invisible shadows over his men's positions — for whenever mortals had to screw their courage to an excruciating pitch of intensity, whenever they had to prepare themselves for battle, 'wave on wave of them settling, close ranks shuddering into a dense, bristling glitter of shields and spears and helmets', they could know themselves passing into the sphere of the divine.

2

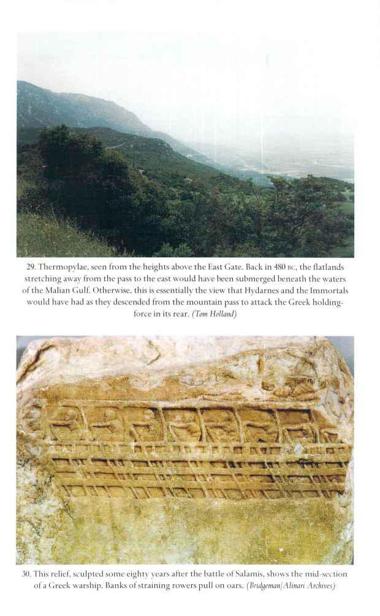

Certainly, it would have been hard to imagine a more eerie portal to it than Thermopylae — the 'Hot Gates'. Steaming waters rose from the springs that gave the pass its name; the rocks over which they hissed appeared pallid and deformed, like melted wax; a tang of sulphur hung moist in the August heat. All was feverish, dust-choked and close. So narrow was much of the pass that at two points either end of it, known as the East and West Gates, there was room for only a single wagon trail. On one side of this road there lapped the marshy shallows of the Gulf of Malis; on the other, 'impassable and steepling',

3

the cliffs of Mount Callidromus, tree-covered over the lower crags, then rearing grey and bare against the unforgiving azure. It was a strange and unearthly spot — and one seemingly formed for defence.