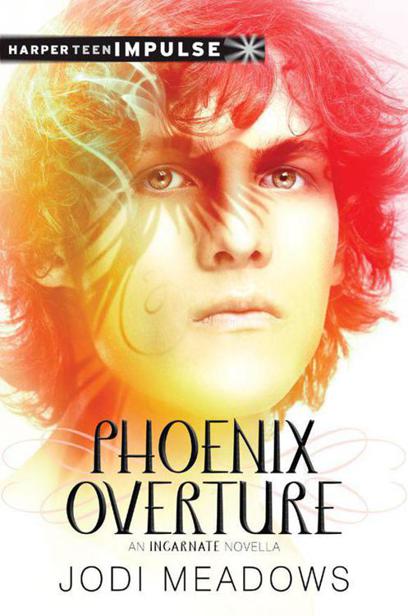

Phoenix Overture

Authors: Jodi Meadows

Phoenix Overture

Newsoul 2.5

by

Jodi Meadows

Dedication

For Kathleen,

Who asked for this.

For Jillian,

Who named Dossam.

And for Gabrielle,

Who’s been answering my music questions for three books and a novella now.

My love and thanks to all of you.

1

“YOU HAVE MUSIC in you, Dossam. Never forget that.”

My mother’s name was Lyric, our family name Harper, and I was born in the wrong time.

When I was small, she took me to a concert hall in the old city. It was remarkably well preserved, though the odor of age and decay hung over it, and the faded red chairs were molded and falling apart.

I drew away from her, farther down the aisle and quiet so my boots didn’t make a sound on the hardwood floor. Arched balconies rose up along the walls, their curtains long ago deteriorated into echoes. Gold paint flaked off the railings, and the marble facades were pockmarked and water-stained, but there were memories in this place, memories of music and longing and emotions that stirred my soul.

“Look on the stage,” Mother said.

The stage stood directly ahead, pitted with age, but strong enough to hold an immense glass curtain, shining iridescent in the light that shot through the colored skylights. And before that, a large black instrument on legs, with a bench that stood empty before the row of keys. Faded gold lettering shimmered on the side of the instrument, too worn for me to read.

“What is that?” I breathed, though I knew. I knew. My heart knew.

I scrambled up the stage, too impatient to bother with the stairs, ignoring Mother’s tiny cry—“Careful!”—and when I stood at last before the piano, chills swept over my body. I couldn’t wait to touch it. I couldn’t bear to risk damaging it, though. Everything here was so old and fragile.

“It’s all right.” Mother stood in the middle of the theater, rows of chairs around her. Light from the ceiling shone on her, making her curly black hair gleam. “Play something,” she said. “You won’t hurt it.”

My heart felt too big for my chest as I reached out and caressed a white key. Though it should have been filthy with grit and age, the key was smooth and clean. The bench was, too, and the rest of the piano wood had been rubbed to a shine, as though someone had prepared it for this moment.

I glanced at Mother, who just smiled mysteriously.

“Play something,” she said again.

A weightless sort of reverence filled me as I slipped onto the bench and let my fingers breeze along the smooth keys. How many people had sat here before me?

“Please never end,” I whispered to the moment, and played a solid, clear note that resounded off the high walls and ceiling. The glass curtain at the back of the stage caught the sound, bounced it back, and my heart felt so wild and free and fulfilled. Music filled me like food or water never would. It filled my soul.

I lost myself, letting my hands explore the keys in search of different notes and patterns and chords, things I only half understood by instinct and by the way they felt right or wrong. I learned my heart there, my hands on the piano, and music flowing all around me, so big and sacred and everything I’d ever wanted.

And when I fell out of the trance, Mother took me in her arms and squeezed. “You have music in your heart, Dossam. I wish this world appreciated that more.”

While I’d sat at the piano, caught in the silver chains of sound, I’d forgotten the outside world. But as we left the domed concert hall, that palace of music, I once again beheld the ruined city, the twisted heaps of metal and memories of another age.

There was music in me, but in this post-Cataclysm world, that didn’t matter very much.

“You’re useless, boy.”

Instinct urged me to duck or run as the belt flew toward my head, but I hardened myself and took the blow; I wasn’t a child anymore, and acting like one would make everything worse.

Thunder snapped in my ears as bright pain flared over my cheek, making my vision white-hot. The world swam around me, but I held myself upright, pushed my shoulders back. I clenched my jaw as Father’s belt retreated.

“Useless and good for nothing.”

I swallowed away the hint of bile in the back of my throat. I wouldn’t speak. Wouldn’t show the way my face stung from the leather strap. Speaking would only make it worse, as I’d discovered years ago. Instead, I gave a shallow nod and kept my eyes down. His grunt indicated I’d done the right thing.

“Do you know what you did this time?”

I glanced at breakfast burning on the wood stove. Fat sizzled in the pan, and the faint scent of smoke lifted through the small kitchen.

“That’s right.” His voice was a growl. A rumble in the earth. “You know how hard I work. You know how the drought is killing everything. And that other people in the Community are starving. And still you have the nerve to burn our breakfast, which I paid for.”

I wanted to apologize, or beg for forgiveness, but I didn’t dare speak. The belt still hung in his grip, like a snake just waiting to strike.

“I work. Your brother works. But what do you do all day?”

Not that it made a difference to him, but I

was

trying to find a job. It was difficult, though, with the drought and plague and never-ending hunger. No one had anything to spare to hire untrained help, and I couldn’t get training without a job.

“There’s a call for warriors.” Father slipped his belt through the loops of his trousers once more, and I released a held breath. “I want you to go.”

To become a warrior? He didn’t know me at all.

“Janan is calling for the best warriors, which means you won’t be chosen to follow him on his quest, but I want you to volunteer anyway. If you’re not going to work with me, or scavenge like your brother, you need to do something useful.”

I wasn’t suited for repair work—a fact painfully obvious after I’d put a dozen new holes in a wall, trying to keep from hammering my fingers—and my brother never allowed me to go scavenging with him, saying it was too dangerous for me.

But of course, those facts meant nothing to Father.

All this was an excuse, anyway. My jobless state—and the still-burning breakfast—weren’t the real reasons he’d taken his belt to my face this morning.

Until a couple of weeks ago, Mother had kept the house spotless. Today there were dirt smears and handprints on the walls. After Father’s search for his ancient leather flask, cupboards hung open, revealing chipped plates, too few jars of canned vegetables and fruits, and a moldy hunk of cheese. The crooked table held piles of old books and scavenged parts, evidence of my brother’s presence somewhere near the house.

“Janan has done everything for this Community, right?” His tone left no room for argument. “He’s the one trying to feed people and stop attacks. If he says he has a plan, I want you to be part of that. Or at least try to be part of that. There’s no chance he’d pick you, but showing up

might

make you appear less lazy and selfish.”

“Yes, sir.” I twisted my hands behind my back, digging my fingernails into my skin to distract from the throbbing in my cheek.

“Noon, okay? That’s when he’s choosing warriors. If you don’t go and somehow make yourself useful, you’ll be sleeping on the streets tonight. People in this house

work

for the privilege of sleeping under a roof.”

“Yes, sir.” Sometimes, those felt like the only words I was allowed to say to him.

“Get this place cleaned up. No more cooking. You’re terrible at it and it’s too hot anyway.” Father yanked the frying pan off the stove and doused the fire. “Then go to the Center and volunteer. Maybe Janan can get you to do something besides hum to yourself all day. Or maybe we’ll get lucky and you’ll gut yourself with your own knife.” He stormed from the kitchen and slammed the front door.

The house rattled with his exit, and the quiet rang shrilly in my ears as I sank into a chair and touched my swollen cheek. It was tender and would bruise, but he hadn’t split the skin this time.

Maybe I’d gut myself with my own knife.

He’d never have dared say anything like that with Mother around, though the sentiment had always been there, hovering just beneath every word he spoke to me. The useless second son. Not strong like him, nor hardy enough to spend days at a time in the old city. Not coordinated enough to be a fighter. Not smart enough to be a scholar.

A year ago, I’d overheard him tell Mother, “If he’d been a girl, he’d at least have been useful for making children, but he hasn’t even got that.”

“No one will ever understand what Dossam has to offer,” Mother had replied, but her defense went unacknowledged. After all, what was music when there was food to grow, or water to collect, or fields to defend? What was music when humanity’s survival was a desperate hope, not a guarantee?

What was music in the face of imminent annihilation by trolls or chimeras or worse?

Useless.

Footfalls thumped on the floorboards, and I tensed, but it was just my brother, Fayden, clomping into the kitchen. He eyed my slumped posture and the blackened bacon smoking on the counter. “What happened this time?” His voice was deep with a note of uncertainty, like my new bruise might truly be my fault.

“He thought I hid the flask.” I heaved myself out of the creaking chair and began closing cupboard doors. “Thanks for warning me you’d done that.”

“You were asleep when I got in.” Fayden picked a slice of bacon from the pan and inspected it with disdain before he took a bite. “Sorry he blamed you.”

He wasn’t sorry. Not really. But I didn’t contradict him as I worked to straighten the kitchen. “He wants me to volunteer for Janan’s quest. If I don’t, he’s kicking me out.”

“What quest?” Fayden grabbed a plate off the counter and swept all the bacon onto it. Grease dripped onto the floor.

“I’m not sure. I didn’t hear the announcement. Father just said Janan wants warriors.”

Fayden barked a laugh. “And he thought

you

should volunteer? A skinny fifteen-year-old who can barely stand to see raw meat?”

It

was

laughable, so I didn’t say anything, just began scrubbing the handprints off the wall.

“Well, maybe it wouldn’t be a bad idea. Janan would never accept

you

, of course, but it would get Father off your back for a while.”

My rag fell to the floor with a wet

plop

as I glared at him. “Do you think so? Do you think that he wouldn’t punish me for being rejected for something he already knows I’m not suited to do?”

“Well, what are you suited for?” Fayden gestured around the kitchen. “Not cooking. Not cleaning. You refuse to go tend plague victims.”

“I don’t want to get the plague!” I scooped up my rag and threw it onto the counter.

“You’re not strong enough to haul water. Scavenging is too dangerous for you.” He slammed the filthy plate onto the counter. “And you couldn’t even—”

“Go ahead,” I growled. “Say it.”

He shoved away from the counter, rattling the plate, and marched from the kitchen. “You know what you couldn’t do, Dossam.”

I wanted to snarl back at him, but he was gone, his boots pounding through the house.

Anyway, he was right.

I knew what I couldn’t do.

2

EVERYTHING ENDED WITH death.

Death claimed entire civilizations, leaving wastelands and ruins, forever stretches of destruction and darkness.

Death claimed memories, the knowledge of what had come before, and promises of futures dreamt.

And death claimed mothers.

It was that loss that cut the deepest, that loss that would never heal. If Father or Fayden recognized the sucking grief inside of me, that consuming hollow that pulled me ever further from them, they never said. If I vanished from the world, would they even notice? Would they care?

They’d been able to continue with their lives, sadder, but no different. But for me, her absence meant I had nothing. She’d been the only person who’d seen the worth of my music, and now she was gone.

The rest of the world kept spinning, even though mine had stopped.

Father wanted to me to meet Janan in the Center at noon. Maybe I would. Or maybe he’d be disappointed in me once again. As I headed away from the Community, stretching my legs to reach the solitude of the woods more quickly, I honestly didn’t know whether I’d make it back.

If I thought I stood a chance on my own, against the rocs and trolls and griffons, I might never go back to the Community. The concert hall was quiet and hidden; there hadn’t been a day since Mother’s death that I didn’t dream about packing my belongings and staying there for the rest of my life.

But I barely survived

with

the Community. I wouldn’t make it a day on my own, especially not in the middle of the old city, without food or clean water.

Sunlight broke through the clouds and their false promise of rain. Insects droned lazily in the heat.

More than anything now, I wanted to be alone with the music of the forest: the wind sighing through the tall conifers, the rustle of feathers as birds took flight, and the bubble of shrinking streams in their rocky paths. The woods sang a dark and lovely melody that haunted my thoughts.

Grief was a chasm in my heart, unaffected by the beauty of the morning-clad woods. I pushed myself down the path. Walking nowhere was better than hanging about the Community, missing someone who could never come back.

A loud

crack

sounded above me, followed by the noise of crashing and cursing. A deep voice shouted from the trees. “Watch out!”

I jerked up just in time to see a metal beam swing toward me, bringing with it a shower of pine needles and cones.

I ducked to the left, but not quickly enough.

Sharp pain splintered down my right arm as the impact shoved me backward, leaving me sprawled over a log. The beam sailed back and forth, inches from my face, held by only a fraying rope.

Rust flaked off the iron and into my eyes as I clutched my shoulder and rolled off the log. “What—”

“Sorry!” The voice came again from above, but a moment later, boots thumped onto the ground next to me. The boy from the trees crouched, his dark eyebrows pulled inward. “Are you okay?”

“No.” My breath coming short and fast, I waved away the stranger’s extended hand and sat up. Conifer needles and cones cracked and dug at my knees, and fire raced down my arm and shoulder blade. My cheek and shoulder throbbed off tempo from each other, encouraging a headache that formed just behind my eyes. “I think you broke my shoulder. What were you doing up there?”

“Nonsense. If I’d broken it, you’d be a lot angrier with me.” The stranger gripped my arm in both hands and shoved. Bone crunched. An inferno ripped through my shoulder and back. But when he sat on his heels and smirked, the pain faded to something more manageable. “How’s that?”

“Better.” I reached around and massaged the muscles, vainly trying to ignore the pop and groan of the tree. A thread of the rope snapped, and the beam dropped lower; if I hadn’t moved, my face would now be a much flatter thing.

“Well. You’re welcome.” The boy nodded at my shoulder. “For fixing that.”

“It’s your fault it was hurt.” I blinked a few times and gathered my nerves before climbing to my feet. My head buzzed and my vision grayed, but—as nonchalantly as possible—I rested my hand on the metal beam that had nearly killed me. I took a few deep breaths. “Who are you?”

“Stef. Well, Stefan, but I like Stef better.” He wore his lean form and square jaw with confidence, and had roguishly narrowed eyes. It gave him the look of a troublemaker—the kind of person I tried to avoid.

This sort of near-death encounter was

precisely

the reason why, too.

“What were you doing up there?” I tipped my head toward the trees. The woods were quiet now, the birds all frightened off by Stef’s loud swearing and the thunderous falling objects.

Stef stood and brushed off his trousers. “I was setting a trap.”

“For what?” Only the occasional twig and spray of needles moved above, brown with thirst as the drought continued its slow assault on the world. “Random passersby?”

“How did you guess?” Stef

thwap

ped my sore shoulder. “No, it’s a trap for trolls. Unless you somehow didn’t notice, they’ve been coming this way more often.”

“I have noticed.” I clenched my jaw and moved away from him, searching the high boughs for a sign of his trap.

“It’s not that I

want

to spend my days out here in the heat, sweating, getting leaves in my hair and down my trousers.” He pulled a brown-green sprig from his shirt and flicked it into the woods. “But I’m good at making things, and if I spent all my time sitting in my house hiding from what’s going on out here, I’d be no better than anyone else in the Community. I have useful skills. I need to use them.”

I kept my attention on the trees and tried to ignore the throbbing in my cheek, shoulder, and ego. “Is your trap invisible?” There was nothing I could see in the trees, and nothing on the ground—except for the beam still hanging suspended from its branch.

“That’s actually my problem. While normally I like my projects to be seamless, no troll is going to get caught in this.” Stef stood beside me and bumped my hurt shoulder again, ignoring the way I cringed. “Look right there. You can see the ropes and pulleys.”

Ah. Now that he’d pointed them out, I could see the rusted metal and crisscross of ropes. “Right. So what’s the problem?”

“It’s okay that the ropes and pulleys are invisible—mostly—but I need something to draw the trolls here.”

“And who says that has to be you?” He couldn’t have been much older than I was. But like he said, his skills were useful—maybe—which might have made a difference in his decision to take the initiative. After all,

humming

at a troll wouldn’t hurt it.

Stef sauntered over to a low branch and pulled himself up to sit on it. “No one said I have to do it.” He shrugged. “My aunts might kill me if they knew what I was doing, but I don’t live with them, and I bet they’ll think differently after I present the trap to the Council. I want the Council to hire me to build more traps, and maybe other useful things in the future.”

How ambitious.

“Anyway,” he went on, “we have to do something, right? The drought is driving the trolls toward the nearest source of fresh water, and that’s our springs and wells. They keep wandering into the Community when they smell food. There was a bad attack a few weeks ago—”

“I know.” I could still hear the screams from the last attack, the crash and bang of collapsing walls, and Mother’s cries as she urged me to flee. And I . . . I’d been rooted by fear. Unable to move. Unable to help. Only when the life had been squeezed from her and the troll slain by warriors did I jerk into a run, through the falling debris and rising dust. “I remember the attack.” I’d never forget it.

He squinted at me. “Right. Well. I want to test out this idea. If it works, the Council will let me put up more traps throughout the forest. Hopefully that will discourage them from coming closer to the Community.”

“What can I do to help?” The words were out before I realized. Troublemaker or no, Stef was doing something about the trolls. Or trying to.

Stef lifted an eyebrow. “What makes you think you’ll be any help?”

“You said you needed something to draw the trolls to the trap. A lure.”

Stef nodded.

“What about shiny pieces of metal?”

“They’re trolls, not raccoons. They don’t care about shiny pieces of metal. Though something shiny

would

help draw their attention.”

“What do they want, then?”

Stef threw up his hands. “How should I know? Do I look like a troll?”

“A little.”

He rolled his eyes.

“My brother is a scavenger. He can take us into the old city to look for something.” I pushed my sweat-dampened hair out of my eyes and glanced westward, but the crumbling towers weren’t visible through the dense forest.

“That sounds like your brother is useful, not you.”

Without another word, I turned and started deeper into the woods, back on the same aimless path as before. Footfalls thumped behind me, but I ignored Stef’s approach, even when his hand landed on my injured shoulder. I shook him off, keeping my face hard against the pain.

“Sorry.” Stef kept my pace. “I was joking. Can’t you take a joke?”

I stopped walking and balled up my fists, but I wouldn’t hit him. I’d never hit anyone in my life, and I wouldn’t let this obnoxious stranger be the first.

Stef glanced at my hands, though, and raised his eyebrows. “Wow. Calm down.”

“Only jerks blame their victim for not being able to handle a

joke

. Or tell them to

calm down

.” I was overreacting. Stef couldn’t possibly know this was a refrain I’d heard too often from Father and Fayden, but the words were out.

Stef held up his hands in surrender, his cocky smirk vanishing. “You’re sensitive.”

“Go lick a plague house.”

“

Really

sensitive.” He made a face. “I said I’m sorry. And I do mean it.”

I sucked in a breath of the hot, muggy air to clear my head. “I’ve had a bad day.” A bad life was more like it. And Mother’s death meant that it would only get worse. She’d liked my music. She’d understood it. Now she was gone.

Stef eyed my shoulder, then my cheek, and nodded. “Guess so.” I didn’t offer details, and—incredibly—he didn’t ask. “Well, do you think your brother would help?”

“He might.” The truth was, I hardly saw Fayden anymore. My encounter with him this morning had been unusual. “You said trolls come looking for water, right?”

He nodded. “As far as anyone’s been able to tell.”

I rubbed at my sore shoulder again, thinking. “What about colored glass? Blue glass, to trick them into thinking there’s water reflecting sunlight. But then they get too close, and

wham

.” I made a tiny explosion with my hands. “Or whatever your invention is supposed to do.”

Stef narrowed his eyes. “Yeah, that might work. I’d have to position the glass just right, so it would mimic running water. But where would we get blue glass? Neither of us can afford to buy anything like that.” He left an opening, but I didn’t tell him how I knew about it. “How many traps could we make from it?”

Where had that “we” come from? I ignored it. “I don’t know. Several.” I hesitated. “I can show you the glass.”

“Right now?” His eyes widened with delight.

I checked the sky; it was almost noon. Who knew how Father would react if I didn’t make it to Janan’s gathering today?

Humiliate myself, or help a potential new friend find a way to defend the Community against trolls?

“Yeah,” I said. “We’ll go right now. It’s in the old city.”

“And your brother?”

I wished I’d never brought up Fayden. Older, stronger, more

useful

. “I think he’s already there, in the old city. I don’t know if we’ll see him. Anyway, I know where the glass is. You should be able to figure out whether it will work by looking at it, right?”

Stef nodded.

“Good. Then let’s go.” I waved him down the path, away from the Community.

The sun beat through the thinning canopy, making sweat drip down my face and neck. Insects buzzed and birds called; the woods grew noisy with thirsty wildlife as we walked. Just before we broke through the woods, Stef stopped and faced me, his expression twisted with amusement.

“It finally occurred to me,” he said. “You didn’t tell me your name.”

“You didn’t ask.”

He raised an eyebrow. “I’m asking now.”

“My name is Dossam.”

“Sam.”

“No, it’s Dossam.”

Stef shook his head. “Well, I like Sam better.”

“

Well

, it’s not your name.”

“I’m the one who has to say it.”

“And I’m the one who has to answer to it.” I bumped his shoulder with mine, cringing as a burst of pain flared. But I smiled, too, because he was smiling.

“I think we’re going to be great friends, Sam.”

In spite of the way my day had started—and the wreck of the last couple of weeks—I believed him.