Pieces of My Heart (28 page)

Read Pieces of My Heart Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

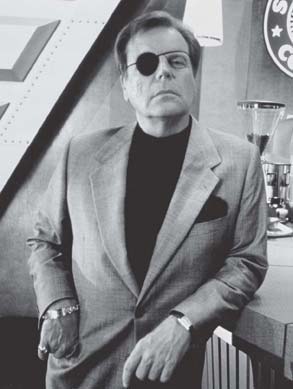

Exuding icy malevolence as Number Two in

Austin Powers

. (

© NEW LINE CINEMA. A TIME WARNER COMPANY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

)

I

never saw Natalie dead, not at the morgue, not at the funeral home. I wanted to remember her alive.

The

Splendour

was impounded, pending an investigation. The autopsy revealed that Natalie had an alcohol level of .14, slightly above the .10 level of intoxication for California. The coroner estimated it as the equivalent of seven or eight glasses of wine, which sounds about right. She also had taken a seasickness drug and some Darvon, but no sleeping pills.

There was a heavy bruise on her right arm, a small one on her left wrist, small ones on her legs, her left knee, and right ankle, and an abrasion on her left cheek.

I’ve had several decades to think about what happened. My conclusion, as well as that of the people who were there and of Frank Westmore, who wasn’t there but who knew the boat and Natalie, is this: while Walken and I were on the deck hashing out our argument, Natalie was in the master cabin and heard the dinghy banging against the side. She got up to retie it. She slipped on the swim step on the stern, hit the step on the way down, and was either stunned or knocked unconscious and rolled into the water. The loose dinghy floated away.

Some people said she was trying to get in the dinghy and drive away from the argument Chris and I were having, but she had gotten in and out of that dinghy a thousand times. She knew that getting in and out of the

Valiant

was very tricky in rough water because the swim step was slippery when it was wet. Even if the water was calm, one person usually held the line to keep the dinghy close to the

Splendour

while the other person hopped in. To do it in rough water in the dark was more than tricky; it was dangerous. Besides that, the state of the controls when they found the dinghy proved that she had never actually gotten into the boat.

Likewise, if she had hold of the dinghy’s tether line, or if she was conscious while she was in the water, she would certainly have screamed or yelled and we would have heard her. My theory fits the few facts we have.

But it’s all conjecture. Nobody knows. There are only two possibilities: either she was trying to get away from the argument, or she was trying to tie the dinghy. But the bottom line is that nobody knows exactly what happened.

Natalie’s body was taken straight to the morgue. I called Mart Crowley and told him that Natalie was dead and asked him to pick me up at the Santa Monica airport. When I got off the helicopter from Catalina, I went directly to psychiatrist Arthur Malin, who told me how to break the news to the children.

“Don’t ever minimize it,” he said. “Don’t try to make it accessible. This is a terrible thing that has happened, it has happened to all of you, and you will have to deal with it together.”

I went to the house, where our core group of friends had already gathered: Roddy McDowall, my son Josh, Linda Foreman, Guy McElwaine, Tom Mankiewicz, Paula Prentiss, Judy Scott-Fox, Liz Applegate, Delphine Mann, and Bill Broder. Dr. Paul Rudnick, my general physician, was there, as was Arthur Malin, who offered to give me something to calm me down, but I didn’t think that was a good idea; I needed to be completely there for our kids.

Natasha, Katie, and Courtney came down the stairs. “I’ve got something terrible to tell you,” I began, “but I want you to know that we’re going to be all right, and we’re going to stay together.” And then I told them their mother had died. Unfortunately, they had already heard about it on television. We cried and held each other. Our lawyer, Paul Ziffren, came and wouldn’t leave. “Promise me one thing,” Paul said. “I will not leave this house until you promise me this. Whatever is written, whatever is said, do not answer any questions from the media. Do not respond to anything. None of that is important. All that is important is you and your family. Promise me this.”

I promised, and I’m glad I did; Paul had just given me very sound advice. For the rest of it, that day and that night I held the children while they cried, and Josh held me while I cried.

Throughout that long, terrible night off Catalina and the next few days, Chris Walken was there. He was at the house as people started coming by, and he stayed through the funeral. He went back to New York afterward. When all the shit came down and people made outrageous claims to the scandal sheets, he never said a word, never made a statement that added fuel to the fire.

I hold no grudge against him; he was a gentleman who behaved honorably in an impossible situation.

I was in a zombie state. It was as if there were a dark film over my eyes; I looked but I didn’t see. I was there for the kids, but otherwise I was going through the motions. The police came a couple of times and asked a lot of questions, which I answered as best I could. There were a lot of people hanging around to make sure that I wasn’t going to go off the deep end, which I would never have done. I may not have known much at that point, but I would never have committed suicide; I knew I had to take care of my kids. They needed their father; their father needed them.

Late on December 1, I came downstairs for a while. Mart Crowley was there, Josh Donen, a few others. The doorbell rang, and Elizabeth Taylor came in. She had just finished a performance of

The Little Foxes

at the Ahmanson. We held each other. “Oh, baby, baby,” she said. “What happened to us, baby?”

Fred Astaire was there, and Gene Kelly came every day. Gene understood loss—his beloved wife, Jeanne Coyne, had died of cancer. He was a solid force, an unshakable wall of support; he would hold me and say, “We’ll get through this.” David Niven was making a film in Europe, but he was on the phone to me every day, talking me through it.

Cumulatively, these friends and my children saved my life.

The funeral itself remains a blur. Natalie’s death was an enormous story all over the world, and when a tragedy like this occurs and there are no facts, or the facts are inconveniently bland, the vacuum is filled with inaccuracies or suppositions. The least offensive was that Natalie’s death made her the latest victim of a jinx on all who had made

Rebel Without a Cause

. The press had completely staked out 603 Canon Drive. We were besieged. When we left for the funeral, publicist Warren Cowan said the kids and I could go out the back way, but I said, “We’re not going out the back door to their mother’s funeral. We’re going out the front door.”

So we went to the cemetery, where we were surrounded by loving and caring friends. There was balalaika music, and all the people Natalie loved were there: Frank Sinatra, Elizabeth Taylor, Fred Astaire, Rock Hudson, Greg Peck, Gene Kelly, and Elia Kazan. Larry Olivier wanted to come, but his doctors wouldn’t let him. Richard Gregson flew in and offered his unconditional support. Hope Lange, Roddy McDowall, and Tommy Thompson delivered the eulogies. Natalie’s pallbearers were Howard Jeffrey, Mart Crowley, Josh and Peter Donen, John Foreman, Guy McElwaine, Tom Mankiewicz, and Paul Ziffren. We had the service, and then we walked out and buried Natalie.

I had chosen Westwood Cemetery because it was close to the house and the kids. They could go and visit whenever they wanted. I was trying to make it as right as I could for the children. I distinctly remember buying a double plot, but the cemetery contended that I didn’t, and they lost the records. Years later, they offered to exhume Natalie and move her to another spot where we could be buried together, but I didn’t want to do that. I just let it go.

After the funeral, we all went back to the house for a wake. President Reagan and Nancy called, and Queen Elizabeth sent a telegram: “On behalf of the Crown and the Commonwealth of Great Britain, I send heartfelt condolences to the family and friends of Mrs. Wagner. The tragic loss of great persons is felt the world over. However, loving memories of Mrs. Wagner will live with us always.” Princess Margaret and Pierre Trudeau also sent telegrams.

It was at this point that I went to bed and stayed there. It may have been for seven days, it may have been for eight. I was catatonic and don’t really remember. I didn’t shower and I didn’t shave. I don’t know if I was in some form of catastrophic mourning; I don’t know if I was in the midst of a contained nervous breakdown. I only know that I was obsessively, continually trying to understand what had happened—to figure out if there was anything I could have done that I didn’t do. It all went round and round in my head, and for those seven or eight days I couldn’t face anything that constituted the world. We had had everything, and our lives had been on an upswing ever since we remarried. To lose Natalie to an incongruous accident fueled by too much alcohol seemed more than tragic—it felt impossible.

Grief mixed with shock is such a difficult state to be in; it’s hard to even describe it. On the one hand, I was numb and felt like I was in some sort of dream state—I couldn’t believe Natalie was gone, but I knew it was true. And despite the shock, which makes you feel like you’re muffled in cotton, my nerve ends were screaming. I was in emotional pain so intense it was physical.

Did I blame myself? If I had been there, I could have done something. But I wasn’t there. I didn’t see her. The door was closed; I thought she was belowdecks. I didn’t hear

anything

. But ultimately, a man is responsible for his loved one, and she was my loved one.

Yes, I blamed myself. Natalie would have felt the same way had it happened to me. Why wasn’t I there? Why wasn’t I watching? I would have done anything in the world to make her life better or protect her.

Anything

. I would have given my life for hers, because that’s the way we were.

She was my love. She was the woman who had defined my emotional life, both by her presence and her absence, and now she was gone and this time there was no getting her back.

Finally, Willie Mae, the children’s nurse, came in and said, “Mr. W., you have got to get up! You have to get these kids to school! You have got to go back to work!” That was the moment that finally penetrated the fog. I got out of bed, got into the shower, and made myself presentable. And then Natasha and Courtney and I went for a walk in the garden, and I told them that it was going to be all right. They had lost their mother; they had to know that they weren’t going to lose their father as well. That was the beginning of my return to the land of the living, and for that I have to thank Willie Mae. We all have saviors in our lives, and she was one of them.

And there was another thing. A doctor gave me a line from Eugene O’Neill: “Man is born broken. He lives by mending. The grace of God is glue.” For me, my children and the people who threw themselves into holding us together were the glue.

It was a strange, disorienting time, filled with strange, disorienting events. In the following weeks, women—famous women—began showing up at my house uninvited. It was soon after Natalie died, and women I had known for years were suddenly bringing food by the house and effecting concern, which I didn’t believe for a minute—they weren’t exactly dressing like they were in mourning. It was such a disconcerting display, and it added a level of discomfort I didn’t really need in my life at that point, this idea that I would be in the market days after my wife died. It was so disrespectful of our relationship and of my love for her.

Nine days after Natalie died, I went back to work on

Hart to Hart

. I had lost ten pounds and most of my emotional equilibrium. Stefanie Powers was in only marginally better shape than I was, but she shepherded me through it. She never let me out of her sight, and if I blew my lines or got upset, she smoothed everything over. On December 12, the police concluded that Natalie’s death was a tragic accident, and the case was closed.

Before that happened, Thomas Noguchi, the Los Angeles coroner, got into the act and ventured some ridiculous speculations, just as he had with Bill Holden, and as he would when he reopened the investigation into the death of Marilyn Monroe. Noguchi was a camera-hog who felt that he had to stoke the publicity fire in order to maintain the level of attention he’d gotten used to. Noguchi particularly enraged Frank Sinatra, who knew the truth and, in any case, would never have allowed anybody who harmed Natalie to survive.

It was after the final determination of Natalie’s cause of death that David Niven came to my—our—rescue. He insisted we get out of Los Angeles for Christmas and come to Europe. I took the kids, Willie Mae, and Delphine Mann, Courtney’s godmother, to Gstaad, where David waited for us for four hours in a blizzard. When we finally got there, he held me in his arms, and then he drove us to a chalet he had rented.

No man could have had a better friend. He had been where I was; he had lost Primmie in a similarly stupid accident, and he had raised their two boys in spite of Hjordis, not with her.

Through the next several weeks, he was with me every day.

Every day

. He never left me alone. He would take me for long walks and talk to me about what I was going through and what he had gone through. He gave me the benefit of the wisdom he had gained from being in the same situation. He told me that this was going to be an incremental process; it was not something you got over, he told me. It was something you learned to live with.

“Don’t make any hard-and-fast decisions,” he said. “Let your feelings go where they want, and don’t let anybody else intrude or tell you what’s appropriate or inappropriate.” David’s wise counsel, and getting away from Hollywood, gave me some distance and enabled me to begin to get my bearings. Those weeks with David were the beginning of the long process by which I put my life back together.

Looking back, I can see that it took years until the haze lifted. What I came to realize, gradually, incrementally, was that Natalie had a tragic death, but she didn’t have a tragic life. She lived more in her forty-three years than most people—felt more, experienced more, did more, gave more. She was loved, fulfilled, and worshiped; she caught her rainbows. The way a life ends doesn’t define that life; the way a life is lived does.