Pilgrimage (15 page)

Authors: Lynn Austin

Tags: #Religion, #Christian Life, #General, #Spiritual Growth, #Women's Issues, #REL012120, #REL012000, #REL012130

As we continue our ascent, our guide decides to teach us a song from Psalm 122, one of the Songs of Ascents (Psalms 120–134). “I rejoiced with those who said to me, ‘Let us go to the house of the Lord’” (v. 1). He explains that Jewish travelers would sing psalms like this one as they made their way to Jerusalem for each of the three yearly pilgrimage festivals. Over time, the words would become as familiar to them as our beloved Christmas carols, sung year after year in celebration. And so we reach the crest of the mountain singing—and panting—and pause to rest.

The view from the summit steals what little breath I have left. The Temple Mount and the Old City of Jerusalem glimmer in the distance, their golden limestone walls and buildings gilded with morning sunlight. Except for the dome of the Muslim shrine that now stands where the Temple once did, this might have been the same view that Jesus and countless other Passover pilgrims saw two thousand years ago. Joy and excitement flood through me as I gaze at the beautiful

panorama. The excitement in Jesus’ day must have been electrifying when, after three years of speculation and controversy, He finally allowed His followers to publicly proclaim that He was the long-awaited Messiah, riding on a donkey.

The crowds cheered and burst into joyous song. They might have been singing the traditional Passover hymns as they climbed this hill, and now the words seem stunningly appropriate: “With boughs in hand, join in the festal procession . . . O Lord, save us (Hosanna!) . . . Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord” (Psalm 118:25–27). The people had sung this psalm all their lives, and now the words and images sprang to life before their eyes in Jesus’ triumphal procession. No wonder their shouts reached across the valley to Jerusalem. To get a taste of their ecstasy, imagine standing in church on Christmas morning singing “Joy to the World, the Lord is come! Let earth receive her king!”—and suddenly, Jesus returns! Our long-awaited Savior and King stands right in front of us! All of the songs we’ve sung and the Scriptures we’ve read that spoke of His second coming are fulfilled before us.

That’s what happened in Jerusalem that day. The ecstatic crowds who greeted their Messiah expected a political leader, and this was His coronation. They waved palm branches, symbols of victory, high in the air the way we wave the flag in a Fourth of July parade. Others shrugged off their cloaks and spread them on the ground to line His path. I have a hall closet filled with jackets and coats, so it wouldn’t cost me much to lay one of them on the ground beneath the donkey’s muddy, trampling feet. But to the people in Jesus’ day, their outer robe may have been the only one they owned, an all-purpose garment that served as a coat during the day, a blanket at night,

a pouch for carrying groceries or babies, and much, much more. To spread it at Jesus’ feet was a costly sacrifice. But what better way to pledge loyalty to their long-awaited king? Scripture was being fulfilled! “Rejoice greatly, O Daughter of Zion! Shout, Daughter of Jerusalem! See, your king comes to you, righteous and having salvation, gentle and riding on a donkey” (Zechariah 9:9).

The day that we celebrate as Palm Sunday was also an important date on the Jewish religious calendar. It was the day that each family chose the lamb—a male without blemish—that they would sacrifice for the Passover feast in a few days (Exodus 12:3). The crowd might have thought they were choosing a king who would bring freedom from the hated Romans, but instead they were choosing their Passover Lamb who would bring a much greater and more lasting liberation.

I long to sing another psalm as we finish resting and start hiking downhill, but the eastern slope of the Mount of Olives looks very different today than it did in Jesus’ day. Our journey takes us through a Jewish cemetery, past thousands and thousands of whitewashed graves. Black-clothed mourners gather around one of them for a funeral, so we proceed in respectful silence. Many of the grave markers have piles of small stones on them left by mourners, reminding me of another episode in the story of Jesus’ triumphal entry.

“Teacher, rebuke your disciples!” the unbelieving Pharisees bellowed above the singing and shouting. They recognized the dangerous political implications of the palm-waving celebration, and knew that the Romans would, too. Jesus refused. “If they keep quiet, the stones will cry out,” He replied (Luke 19:39, 40).

Israel has the rockiest terrain I have ever seen, so the shouts from millions of cheering stones would have been deafening. But the Pharisees, who knew the Scriptures by heart, would have recognized Jesus’ reply as a quote from the prophet Habakkuk. Instead of rebuking His followers, Jesus was rebuking them! “Woe to him who builds his realm by unjust gain to set his nest on high . . . The stones of the wall will cry out” (2:9, 11). Habakkuk warns of God’s judgment against corruption and bloodshed, and ends with a magnificent Messianic prophesy: “For the earth will be filled with the knowledge of the glory of the Lord, as the waters cover the sea” (v. 14). Jesus was telling the Pharisees that God would soon judge them. But the joyful, cheering celebration that began on Palm Sunday could never be stopped.

We find more enterprising Arab boys waiting for us at the bottom of the hill, hawking blurry postcards and flimsy souvenirs. “One shekel! One shekel!” they call out. Our bus is also waiting. It’s too difficult to walk to the Temple Mount from here and cross the modern highway that zooms through the Kidron Valley. Besides, the Golden Gate that Jesus would have entered to reach the Temple is sealed shut. But I look back at the Mount of Olives as we drive away, still picturing that Palm Sunday and imagining the wonder and joy that must have overwhelmed the disciples.

Jesus had explained to His followers what would happen to Him when they reached Jerusalem, but I don’t think they really believed Him. I’m sure that Peter, James, John, and the others still clung to the hope that the Messiah would be a political king who would sit on David’s throne and govern Israel. The Palm Sunday victory parade and the masses of people pledging their allegiance to Him probably buoyed

those hopes. And memories of that celebration probably added to their despair and confusion when the king they had chosen turned out to be a lamb who was sacrificed on Passover.

I have publicly proclaimed Jesus as my Messiah and Lord, but like the Palm Sunday revelers, I wonder if I’m also guilty of creating false expectations of who Jesus is and what He wants to do in my life. I have prayed for salvation from painful circumstances as if expecting Him to make all my troubles march away like retreating Roman soldiers. When they don’t, I’m disappointed and discouraged. But maybe, instead of changing my circumstances, Jesus wants to use those circumstances to change me. Isn’t that what His sacrifice on Calvary was really about? To set me free from my sins so that I could become more like Him?

Before I toss my coat in His path in a giddy Palm Sunday parade, swept along with the crowd, perhaps I need to examine more carefully what Jesus really meant when He said, “In this world you will have trouble. But take heart! I have overcome the world” (John 16:33).

The Last Supper

The room bears no resemblance to the one in the DaVinci painting. We have climbed a steep, narrow set of stairs to an upper room, arranged as it might have looked for the Last Supper. The shadowy space has few windows, the plain stone walls are unadorned. Lit only by oil lamps, it seems more like evening in here than daytime. A long, low table fills the center of the room, surrounded by rugs and mats. We gather around it, reclining on the floor with our elbows propped on

the table—something my mother would chide me for doing, but it’s the only way to eat comfortably.

In Jesus’ day, this table would have held all the traditional items for the Passover meal: bitter herbs and salt water to remind them of tears and slavery; a gooey concoction called

charoset

to symbolize their labor with bricks and mortar; unleavened bread to remember their hasty departure; and roasted lamb to recall the blood of salvation on their doorposts. Jesus and the disciples had celebrated Passover since childhood, eating the same foods, singing the traditional songs, reading the well-loved Scriptures, and so every feature of this meal was familiar to them. “I have eagerly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer,” Jesus began. “For I tell you, I will not eat it again until it finds fulfillment in the kingdom of God” (Luke 22:15–16). He was about to teach the disciples His final lessons, so they must be important ones.

Once our group has gathered around the table, our guide has a surprise for us. “We are going to wash each other’s feet,” he says. I stifle a groan. I don’t want to bare my feet in public, much less have someone near enough to smell them. I’ve been hiking all morning in sweaty shoes—and hiking for a week in the desert before that in the same pair. I’ll sit back and watch, thank you.

I’m not the only one who balks. The ritual exposes our stubborn American individualism. We don’t want anyone to serve us so intimately, glimpsing our ugly blisters and the dirt we keep carefully hidden. Nor do we like to see other people’s warts and calluses. Kindly keep your imperfections and wounds hidden from view.

If I’m reacting with obstinate pride and uneasiness, how must the disciples have felt when Jesus announced that He

was going to wash their feet? Imagine their disbelief when He removed His robe and dressed as a servant to do the menial job of hauling water upstairs, then kneeling to perform a slave’s task. The disciples walked on dusty, manure-strewn roads all day. None of them had Odor-Eaters in their sandals. None of them had gone for a pedicure beforehand. Peter folded his arms and shook his head in defiance. “No. You shall never wash my feet” (John 13:8). He had the nerve to say

no

to Jesus?

Was I just as guilty?

Seeing myself in Peter’s reaction, I have a change of heart. I submit to the ritual, knowing there might be an important lesson to learn.

“Partner with a stranger,” the guide tells us, “not a family member or friend.” I kneel down in front of a woman I barely know and remove her shoes, then bathe her feet in the basin of water. When I finish, she washes mine. It is very humbling to kneel and serve, even more humbling to be served. Yet this was precisely the point that Jesus was trying to make. We need to be vulnerable and honest with each other—and with Him. He knows all of our warts anyway, so why not bring them into the light and let Him wash us clean? And the hands that He uses to do it are those of my fellow Christians, His body.

“Do you understand what I have done for you?” Jesus asked when He was finished. “Now that I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also should wash one another’s feet” (John 13:12, 14). Disciples are supposed to watch the Master and imitate His actions, not merely parrot His words. If He humbled himself in the role of a servant, then I need to, as well. And if He tells me to take off my shoes and stop hiding the dirt and ugliness so that my church family can

help me get clean, do I dare fold my arms and shake my head in defiance?

It occurs to me that Jesus must have washed Judas’ feet. I recall a time when I felt wounded and betrayed by the words and actions of another Christian, but if I want to follow Jesus’ example, my response should be to show her grace. To not only forgive her but to serve her. I can do neither on my own, only with His help.

As we take our places at the table again, Jesus’ concluding words prick my heart: “Now that you know these things, you will be blessed if you do them” (John 13:17).

And I will miss out on a great blessing if I don’t.

Communion

A real Passover meal is an extended celebration, beginning at sundown and lasting late into the night. We can’t recapture its depth in a mere hour, but our guide shares some of the highlights with us. For Jesus and His fellow Jews, the meal commemorated their covenant with God and rescue from slavery in Egypt. But as Jesus celebrated it with His disciples on the night before His crucifixion, He transformed the traditional Passover wine and bread into our commemorative meal, celebrating His new covenant and our rescue from slavery to sin. Each time we partake of His body and blood, we’re affirming that we are His disciples, that we will do whatever the Lord tells us to do instead of following our own stubborn desires.

If we were eating a full Passover meal here in this room, we would drink four cups of wine throughout the course of the evening. Each cup represents one of the four promises God

made to Israel on that first Passover night in Egypt (Exodus 6:6). The first is, “I will bring you out from under the yoke of the Egyptians.” The second, “I will free you from being slaves to them.” And the third is the one I believe Jesus drank when He said, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood, which is poured out for you” (Luke 22:20). It represents the promise, “I will redeem you with an outstretched arm” (Exodus 6:6). When His Passover meal ended a few hours later, His redemption would begin.

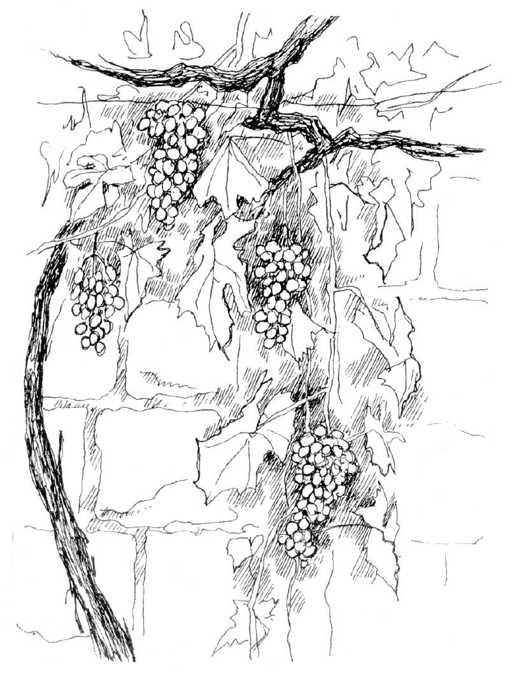

Grapevine

There remained a fourth cup of wine, but Jesus said, “I will not drink again of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes” (Luke 22:18). He drank that final cup as He took a sip of wine while suffering on the cross, fulfilling the

final promise, “I will take you as my own people” (Exodus 6:7). Then He announced, “It is finished” (John 19:30).