Pirate Freedom (11 page)

Authors: Gene Wolfe

When I opened my eyes again, I saw that I was standing in one of the drawings he used to make for geometry. The mast was a line, the mainsail a plane, the boom another line, and the shrouds that braced the mast were lines, too.

And I could change that drawing

.

I had been thinking about the Bermuda rig I had seen, and wishing we had that instead, because I felt sure it would be faster. I could not change over the

Windward

to a Bermuda rig, because I did not have a taller mast to step in her. I could have shortened the boom—we had a saw and a few other tools—but I needed a new mast, and I did not have it. What I understood then was that I could change other things.

During the next watch I made some drawings for myself on a blank page of the logbook. I put letters at the corners, the way we did in class. The backstay ran up from deadeye "A" to "B," the head of the mast, and so forth. I will not give all the rest, but the end of the bowsprit was "I."

After that I got Lesage and Red Jack to look at it, and drew a three-cornered sail set on the forestay just as if it were a mast. One corner was the top of the mast, one was the end of the bowsprit, and one was cleat "J" on the deck that we would have to put there.

"The stay's as stiff as a yard," I said, "because it's so tight. So why couldn't we do that?"

Lesage pointed out that we would have to cut a square piece of sailcloth cattycornered, and half of it would be wasted.

"It won't be wasted," I told him, "it will be a spare J-I-B sail."

Lesage did not think my J-I-B sail would work, but Red Jack wanted to try it. So did I, and I was captain. We did not have a real sailmaker, but it was pretty simple and a couple of hands cut it and sewed the edges in one watch. We put cleats on each side a little forward of the waist, bent our new sail, and it worked so well we almost stopped using the spritsail.

THE

WEALD

WAS

already there when we got to Tortuga. Ned and I launched the little jolly boat that was the only boat our sloop had, and he rowed over to her. I told him to wait in the boat for further orders and went aboard. There are things about my life I cannot explain, and one is why I remember certain things clearly when I have forgotten a lot of others. One that I remember very, very clearly from those days is telling Ned I did not think I would be long, turning away, and grabbing the sea ladder. I never set foot on the

Windward

again—or saw some of her crew again either.

Capt. Burt shook my hand, took me into his cabin, poured me a shot of rum, and asked for my report. I gave him the works—everything that had happened. At the end, I pulled up my shirt, took off my money belt, and counted out his shares of the ship money and the slave money.

He thanked me and slapped my back. "You're a captain now, Chris my lad."

I nodded. "I know it."

"The sort I look hard for and seldom find, eh? I'm glad to have found you. We've had better prizes than the

Duquesa

since you've been gone. Much better. Add your sloop and your men to what we've got already and we might have a shot at a galleon." He stopped, waiting for me to say something.

I thought hard before I spoke. I knew what I had to say, but it was hard to get out because I wanted to do as little damage as I could. "You told me you

liked me once, sir. I like you, too, and I hope anything you try works out. The men I brought are yours, and so is the

Windward

. But I won't take part."

He had his hand on the butt of his pistol by the time I finished. He never drew it, though, and I've always remembered that about him. All he said was "I knew it was comin', eh? Still, I tried."

He kept me chained in the hold for three days after that. They did not always remember to feed me, but when they did the food was decent. On the third day, the man who brought it told me the captain was going to maroon me, which is what I had been figuring all along.

Where I had been wrong was the size of the island. I had been figuring on a little one, one that might take a day to walk all the way around if I was lucky. This looked like the mainland—mountains rising out of the sea, all covered with the greenest trees in the world. Capt. Burt and I sat in the back of the longboat, so I got a good look before she beached.

We got out, just the captain and me, he unlocked my chains and tossed them to the cox'n, and we walked up the beach a ways. I was barefoot, in a slop-chest shirt and pants to match. He had that blue coat with the brass buttons that he never buttoned, and he was carrying a musket. I thought it was probably because he was afraid I might jump him.

"Know how to use one of these?" He took it off his shoulder.

I said, "I can load and shoot one, but I'm no great shot."

"You will be, Chris. This is yours now." He handed it to me, and the pouch with it.

I stood the musket on its butt and opened the pouch. There was big powder flask, a little flask for priming powder, half a dozen bullets, a bullet mold, flints, and some other stuff, like the wrench you use to tighten the hammer jaws and the little piece of soft leather that lets them get a grip on the flint.

I had been too busy looking at the island to notice that he was wearing my dagger, but he was. He took it off and gave it to me. "This was yours already."

I tried to thank him. I knew he was a murderer and a thief, and those things really bothered me back then, but I tried anyway.

"This is yours, too, eh?" He opened up his shirt and untied the money belt I had bought in Port Royal. "Your share's all there, every farthin'. Count it if you like."

Since there was no point in not trusting him, I did not. I just took off

my shirt and put on the belt. I kept that one up until the time the Spanish robbed me.

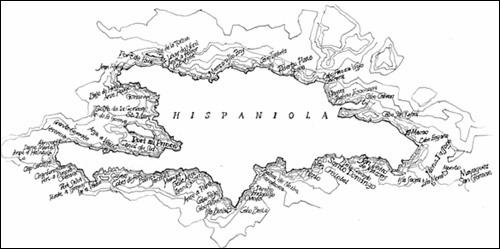

"This is Hispaniola," he told me. "There are wild cattle here—quite a lot, apparently. Wild Frenchmen, too. Boucaners is how the Frogs say it. They shoot the cattle, dry the beef, and trade it to ships that stop here to buy it." He grinned. "Make first-rate pirates, the buccaneers do. I've a dozen or so, and I'd take another dozen if I got the chance. They'll cross your bow before long if the wind holds."

He surprised the heck out of me when he held out his hand. As soon as we had shaken hands, he turned as serious as I ever saw him. "They're dangerous friends, Chris, and foes hot from Hell. Make friends if you can, but 'ware shoals. If they see your gold, you're as good as dead."

If I had loaded as fast as I could—I mean, as fast as I could back then—I might have gotten a shot at Capt. Burt as the longboat took him back to the

Weald

. I thought of it, but what good would it have done? When your only friend is a murderer and a thief, those things do not seem as bad as they used to.

How I Became a Buccaneer

THE BUGS WERE

bad. That is the first thing I have to tell about Hispaniola, because if I do not say it right up front, Hispaniola is going to sound like paradise. The bugs were terrible. There were stinging gnats so little you could hardly see them. There were red flies that went straight for your face every time. Where they were bad, you had to break off a branch and wave it in front of your face for hours and hours. Worst of all were the mosquitoes. There were a lot of good things about Hispaniola, but there was not one day there when I would not have been glad to go back to the monastery or the

Santa Charita

.

I did not know about the bugs when Capt. Burt left me on the beach. There was a fresh wind blowing, and when there was a wind the beaches were clear of bugs. What I did know about Hispaniola was that it was not a desert island. There were people who lived there all the time, just like Cuba and Jamaica. I thought the best thing for me to do would be to find some and

try to get them to help me. There had been Spanish maps on the

New Ark

, and I had spent a lot of time looking at them. The big town on Hispaniola had been Santo Domingo, and it had been on the south coast of the island over toward the east end. I did not know whether I was toward the east end or the west end (which is really where I was), but I could tell from the sun that I was on the north coast.

If I had been smarter, I would have walked east, following the coast. What I tried to do instead was cut across to the south coast, walking southeast so as to be near Santo Domingo when I hit it. If I had known more about Hispaniola, I would have known how dumb that was.

When I started out, I was hoping to see some of those wild cattle Capt. Burt had told me about. I thought I would kill one and cook some of the meat. By the time I had been walking an hour or so, I just wanted to get away from the bugs. I finally found a place that was clear of them, up on one of the mountains. It was rocky and wide open except to the west, but there were no bugs and that was where I spent the night. The next morning I found a spring, drank as much water as I could hold, and started walking again. I did not have a clear idea of how big the island was or how far I could walk in a day, and thought I could probably cross it in three days, and maybe in two. Just for the record, Hispaniola is about seventy-five miles across, and a hundred or so the way I was going. Walking the way I was, navigating by the sun and working my way through rough country, ten miles would have been a really good day.

Just for the record, too, I did not just look at maps after that. I studied them. There were maps on the

Magdelena

, good ones, and by the time I was through with them I could have drawn them myself.

Now it seems to me like it was forever, but I think it was probably the second or third day when I met Valentin. I came out of the rain forest onto a chip of prairie, and I saw a naked man over on the other side. I yelled "Bon jour!" and he was gone as quick as that. I went over to where I had seen him and started talking all the French I could lay my tongue to. I said that I was lost, that I did not want to hurt anyone, that I would pay somebody to help me and so on.

Pretty soon somebody said, "You are not French." He said it in French, of course, and he sounded scared.

"Non," I yelled. "I just speak it a little. I'm American."

"Spanish?"

"American!"

"Not Spanish?"

"Italian! Sicilian!"

"You will shoot me?"

I wanted to say heck no, but I was afraid I would screw it up. So I just said, "Non, non, non!" and laid my musket down. Then I held up my hands, figuring he could probably see me even though I could not see him.

There was a lot more talking before he finally came out. He was about my age, had not had a shave or a haircut in a long, long time, and wore nothing but a strip of hide in front. There was another strip, pretty thin, around his waist that held up the first one, and his knife hung from that, too, in a sheath he had made himself. I gave him my hand and said, "Chris." After a minute, he took it like he had never shaken hands in his life and told me his name. Pretty soon his dog came out. Her name was Francine. She was a pretty good dog, but a one-man dog. She never did trust me a lot.

From the time I had eaten on the

Weald

until the time I met Valentin, I had eaten nothing but a couple of wild oranges, and by then I was plenty hungry enough to eat Francine. I asked Valentin whether he had anything, and he said I had a gun and he would show me where there would be good shooting.

We walked another three miles or so before Francine flushed a wild pig. I shot at it and missed, but Francine got out in front of it and turned it back toward us. It went past us faster than I would ever have thought a pig could run, but Valentin cut it with his knife as it went by just the same. Francine went after it, yelping now and then to let us know where she was, and we listened for her and tried to follow the blood trail the pig had left.

Pretty soon Valentin stopped me and pointed. "In there." It was thick cane, but I listened for a minute and he was right. I could hear Francine growling and a

click-click

noise I did not understand back then. When I had reloaded, priming the pan and all that, I went in with the safety catch off, trying to keep the muzzle down all the time and reminding myself that if I shot his dog, Valentin would probably go for me with his knife.

Francine was keeping the pig busy, dodging the pig's short rushes and trying to get behind it. When I fired, I was so close I could almost touch the pig with the end of the barrel.

I do not think I have ever been more aware of the delay between the time I pulled the trigger and the shot than I was right then. It is only a little piece

of a second, but that was when I began to understand that little piece of time is the key to good shooting. A man who thinks his gun is going to fire when he pulls the trigger is going to miss. Pretty soon I learned to wait for the hammer to fall, for the powder in the pan to flash, and for the gun to fire. It is fast, sure. But it is during that quarter second or so that the man who pulls the trigger has to have his sights right where he wants the bullet to go. When I had trained myself to do that every time I was a good shot.