Plymouth (15 page)

Authors: Laura Quigley

Charles Lock Eastlake, then just twenty-two years old, painted a portrait of Napoleon shown standing on the deck of the HMS

Bellerophon

while the ship was anchored in Plymouth Sound. The huge painting was based on sketches of Napoleon taken with the Emperor’s permission: Napoleon himself even sent the artist parts of his uniform to ensure the painting’s authenticity. Eastlake went on to become president of the Royal Academy.

In the confusion of post-revolutionary France, Napoleon was declared Emperor and his forces became a major threat to trade routes and the British Navy. In 1803 Napoleon formulated a plan to invade England, but the dying Admiral Horatio Nelson defeated the French Navy at the Battle of Trafalgar. Nelson had close ties with Plymouth, having been awarded Freedom of the City in 1801. Lieutenant John Pollard from Cawsand is still known as ‘Nelson’s Avenger’, thought to be the man who killed the French sailor who shot Nelson.

After a series of humiliating military failures, including the disastrous retreat from Russia, Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to Elba, where he escaped and recruited French forces to take Paris. His ambitions came to an end in 1815 at the Battle of Waterloo.

Napoleon, escaped from Elba. (LC-DIG-pga-04089)

England and her allies restored Louis XVIII to the French throne, and Napoleon once again became a prisoner, exiled to St Helena. There, in the damp accommodation, he eventually died of stomach cancer (though some say he was slowly poisoned).

During the Napoleonic Wars the French prisoners captured and held in Plymouth were poorly treated. Hundreds were hanged. Those imprisoned in the Citadel were whipped on arrival. The worst offenders went to the Black Hole, a noxious gaol on Fore Street. The remainder were held in appalling conditions, the prisoners complaining bitterly about the meagre food and decrepit cells. Sickness ravaged their numbers. Some of the prisoners gained extra food by corrupting the guards; this they sold on to their fellow prisoners in a black market.

![]()

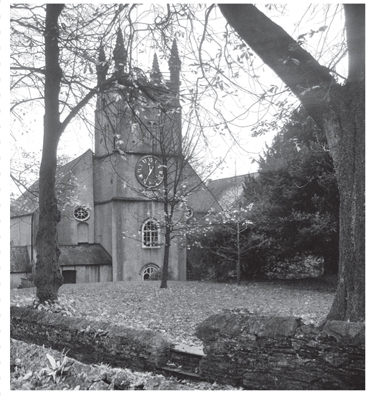

In an isolated corner of Stoke Damerel churchyard is the gravestone of John Boynes, the markings indicating that he was Jewish and therefore buried apart from the others. The gravestone reads: ‘To the memory of John Boynes, late Stone Mason of His Majesty’s Dock Yard, who was unfortunately drowned between the Island and Point returning from seeing Bonaparte in the Sound, 17th July 1815. Aged 35 Years.’

The grave of John Boynes.

![]()

In desperation, the French prisoners resorted to gambling to raise money for their keep, frequently losing their clothes in the process. During the worst winter months, French prisoners were seen naked on board the prison ships in Millbay, forced to sleep in rotting straw. Some were so weak from lack of food that they fell out of their hammocks and broke their necks.

In 1799 hundreds of French captives burrowed under the walls of Millbay Barracks and escaped. A ‘hue and cry’ was raised throughout the West and haystacks and outhouses were frantically searched for the famished and footsore soldiers. A number of merchant ships were discovered in the Sound deliberately concealing the wretched escapees, while two prisoners were found in a hotel in Honiton, having paid for a boat and a coach to get them there.

![]()

The Reel Cinema behind the modern Theatre Royal in Plymouth is haunted. It was built in 1938 over a graveyard containing the remains of Napoleonic prisoners of war. However, the ghost most frequently reported is that of a woman who sits in the front rows of screen two: during the film, she vanishes into thin air.

![]()

1830

INVASION OF THE BODY-SNATCHERS

I

N 1830 THOMAS

Goslin and his pretty wife Louisa moved into Number 4 Millpleasant, a rather genteel address. Thomas Goslin, thirty-nine, was by all accounts a prosperous-looking man, a little short at 5ft 4in, with grey eyes and brown hair. He was known to wear expensive clothes, including a fine black coat. His wife was ten years younger, a tiny 4ft 11in and always well-dressed, and they brought with them three servants: Richard Thompson, his wife Mary and another man called John Jones (sometimes known as John Quinn), all in their twenties. The Goslins declared to their neighbours that they were delighted with their new home: so quiet, and in such a secluded area! They didn’t seem to mind that it was so close to the walled graveyard of Stoke Damerel church.

Of course, they failed to mention that they were all notorious body-snatchers.

Stoke Damerel church.

Body-snatching has a long history in Britain. As medical schools in London and Edinburgh swelled with students, so the need for fresh bodies increased. Each student needed at least three bodies to practise surgery and to study anatomy. Meanwhile, the number of hanged felons decreased year on year as more convicts were transported to the colonies. This may still have been, in practice, a death sentence for many, but nonetheless it left the surgeons and students with fewer and fewer fresh corpses to study. In the very early days, desperate anatomists dug up the recently buried themselves, but in 1721 apprentice surgeons were legally forbidden from exhuming the dead. So many schools offered payment for a good supply, usually through intermediaries. They thereby established the gruesome profession of the ‘resurrectionist’.

In the eyes of the law, a dead body had no value and did not belong to anyone. The theft of a body did not count as a felony, therefore, but as a misdemeanour – providing that no actual possessions were stolen at the same time. Heavy fines or short prison sentences were the most a ‘resurrectionist’ would expect if caught, so the trade was seen as a relatively safe one. It was also extremely lucrative: a body-snatcher could be paid anything from forty-two shillings to £14 for a fresh adult corpse, so a quiet graveyard became a goldmine to those prepared to get their hands dirty. Jewish bodies were particularly prized, their quick burials ensuring the deceased had not decomposed, though the difficulties of moving a body still in a state of

rigor mortis

had to be considered. Even a decayed body could provide a good supply of teeth to sell. The London Medical Schools quietly left a supply of sacks outside the door for their suppliers’ use and never asked any questions.

![]()

Just before Thomas’ arrival in Plymouth, the Plymouth Medical Society petitioned the council for facilities to procure subjects for dissection. Had Thomas Vaughan perhaps received an invitation to visit?

![]()