Political Timber (15 page)

Authors: Chris Lynch

I went out and started down the driveway, and she stopped me.

Pssst.

“I’m not supposed to tell you, but I don’t see why I shouldn’t: Your father did vote for you. He couldn’t resist.”

The telling of that seemed to make her feel so good.

The hearing of it made me feel so good.

I met Mosi at the foot of the drive. I’d forgotten how much I liked walking.

“

A BEATING OF BIBLICAL PROPORTIONS,”

trumpeted

The School Newspaper.

I was not, apparently, going to be student body president either.

The candidates are required—kind of a throwback to sitting in the stocks on the town common—to go around and take down all of their old posters the day after the beating. Mosi, ever the sport, helped me.

“So, you all sad and stuff now?” he asked as he stripped off the few remaining strands of a poster in the gym.

“Um...” I felt it out as I spoke. “Yes, I suppose so. Not the

what,

really, since none of that crap was what I wanted anyhow, but more the

how.

The how hurt. ’Cause I got sucked in, to the whole glam thing, and wound up wanting what I didn’t really even want, then getting all twisted up and slapped around and then left with nothing to show at all.”

“Hmmm,” Mosi said. “I think I follow. Can I say something?”

I shrugged. And meant it.

“I’m kinda not too sad you lost.”

“You don’t say.”

“Promise you won’t get mad.”

“I promise.”

“I kinda... didn’t help you.”

“So what, Mos? In the end, I kinda didn’t help myself.”

By this time we had gathered most of the Foley campaign debris and were out on the football field, heading for the poster on the end-zone wall.

“No, Gordie, I mean, I really didn’t help. Like, a lot I didn’t help.”

“Spit, Mosi.”

“I was in the I-Team.”

There was a long silence between us. When I turned on him, he was raising his hands in self-defense.

“Duh, Mosi. I mean, how could I

not

know it was you?”

“Oh, ya,” he said. “You’re so smart, tell me why I did it, then. ’Cause

I

don’t even know why I did it, so howdya like that?”

“Yes you do. We’ve been talking about this senior thing for three years now, what all we were going to do and how fun it would be. Then we got there, we weren’t having any of it, because of all the stupid shit I was doing. I didn’t have the brains to quit, so you did it to me, like one of those mercy killings old couples do to each other.”

As I said it, I remembered the reason Mosi was always my friend, often my only close friend. The thing that tended to make Mosi different from everybody else, as if he wasn’t already different from everybody else. Mosi cared.

“Thanks,” I said. “Ya friggin’ dope.”

“You’re welcome,” he said, smiled, and slapped me a little too hard.

“You know, Mos,” I said, rubbing my cheek. “You were the only person other than my grandfather—and

he’s

demented—to actually think I had a chance to win.”

He sat on the ground near me. “I was pretty worried for a while there,” he said seriously.

In bed that night I lay there trying to pull it together. What happened?

I killed my da—that’s what he said. But I rediscovered my Mosi. I found out stuff about myself by finding out what I was not. I was not Fins Foley’s boy, which was good. But I was not his grandson anymore either.

I found out that the price, for finding out, is high.

I was not political timber, and I was not a media star.

The rest was still out there, to be found out.

I turned on the radio, tuned in to Matt’s show and my new replacement intern/personality. The nature of the talk had clearly shifted away from politics. Tonight’s subject was titled “The Seven Deadly Erogenous Zones.”

“And we have a challenge,” Matt wheezed. “Sweaty Betty urges our listeners, male and female, to call in and name them all.”

“Or to ask advice on all things worldly,” Betty kicked in.

Now this, I thought, was a show.

This

made sense. Here was a bona fide media personality, and a person who knew who she was.

I smiled, pulled out the FinsFone, which had not yet been canceled, and I dialed.

Chris Lynch (b. 1962) was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the fifth of seven children. His father, Edward J. Lynch, was a Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority bus and trolley driver, and his mother, Dorothy, was a stay-at-home mom. Lynch’s father passed away in 1967, when Lynch was just five years old. Along with her children, Dorothy was left with an old, black Rambler American car and no driver’s license. She eventually got her license, and raised her children as a single mother.

Lynch grew up in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood, and recalls his childhood ambitions to become a hockey player (magically, without learning to ice skate properly), president of the United States, and/or a “rock and roll god.” He attended Catholic Memorial School in West Roxbury, before heading off to Boston University, neglecting to first earn his high school diploma. He later transferred to Suffolk University, where he majored in journalism, and eventually received an MA from the writing program at Emerson College. Before becoming a writer, Lynch worked as a furniture mover, truck driver, house painter, and proofreader. He began writing fiction around 1989, and his first book,

Shadow Boxer

, was published in 1993. “I could not have a more perfect job for me than writer,” he says. “Other than not managing to voluntarily read a work of fiction until I was at university, this gig and I were made for each other. One might say I was a reluctant reader, which surely informs my work still.”

In 1989, Lynch married, and later had two children, Sophia and Walker. The family moved to Roslindale, Massachusetts, where they lived for seven years. In 1996, Lynch moved his family to Ireland, his father’s birthplace, where Lynch has dual citizenship. After a few years in Ireland, he separated from his wife and met his current partner, Jules. In 1998, Jules and her son, Dylan, joined in the adventure when Lynch, Sophia, and Walker sailed to southwest Scotland, which remains the family’s base to this day. In 2010, Sophia had a son, Jackson, Lynch’s first grandchild.

When his children were very young, Lynch would work at home, catching odd bits of available time to write. Now that his children are grown, he leaves the house to work, often writing in local libraries and “acting more like I have a regular nine-to-five(ish) job.”

Lynch has written more than twenty-five books for young readers, including

Inexcusable

(2005), a National Book Award finalist;

Freewill

(2001), which won a Michael L. Printz Honor; and several novels cited as ALA Best Books for Young Adults, including

Gold Dust

(2000) and

Slot Machine

(1995).

Lynch’s books are known for capturing the reality of teen life and experiences, and often center on adolescent male protagonists. “In voice and outlook,” Lynch says, “Elvin Bishop [in the novels

Slot Machine

;

Extreme Elvin

; and

Me, Dead Dad, and Alcatraz

] is the closest I have come to representing myself in a character.” Many of Lynch’s stories deal with intense, coming-of-age subject matters. The Blue-Eyed Son trilogy was particularly hard for him to write, because it explores an urban world riddled with race, fear, hate, violence, and small-mindedness. He describes the series as “critical of humanity in a lot of ways that I’m still not terribly comfortable thinking about. But that’s what novelists are supposed to do: get uncomfortable and still be able to find hope. I think the books do that. I hope they do.”

Lynch’s He-Man Women Haters Club series takes a more lighthearted tone. These books were inspired by the club of the same name in the

Little Rascals

film and TV show. Just as in the Little Rascals’ club, says Lynch, “membership is really about classic male lunkheadedness, inadequacy in dealing with girls, and with many subjects almost always hiding behind the more macho word

hate

when we cannot admit that it’s

fear.

”

Today, Lynch splits his time between Scotland and the US, where he teaches in the MFA creative writing program at Lesley University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. His life motto continues to be “shut up and write.”

Lynch, age twenty, wearing a soccer shirt from a team he played with while living in Jamaica Plain, Boston.

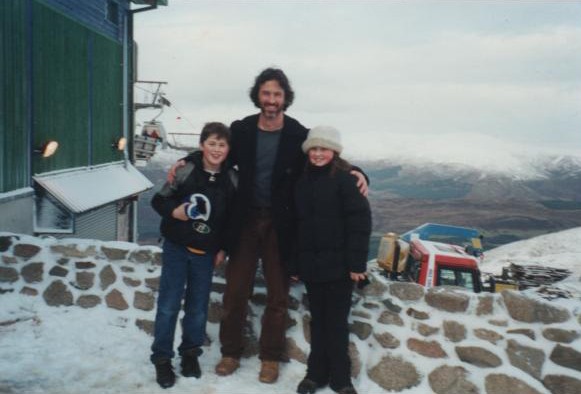

Lynch with his daughter, Sophia, and son, Walker, in Scotland’s Cairngorm Mountains in 2002.

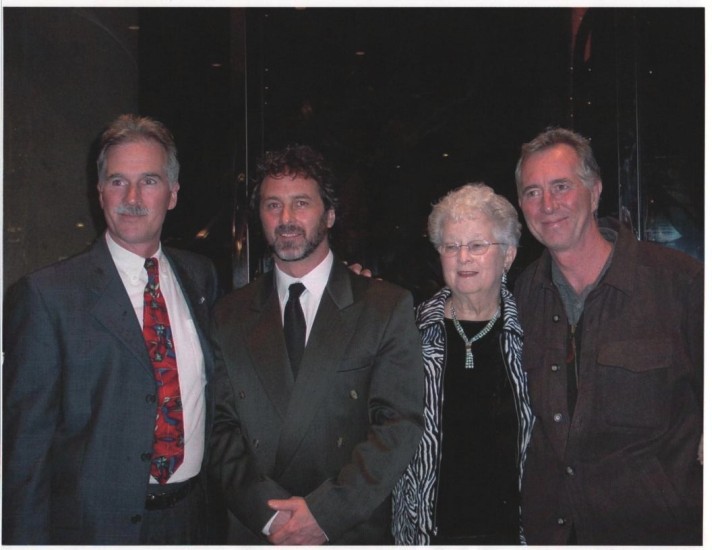

Lynch at the National Book Awards in 2005. From left to right: Lynch’s brother Brian; his mother, Dot; Lynch; and his brother E.J.

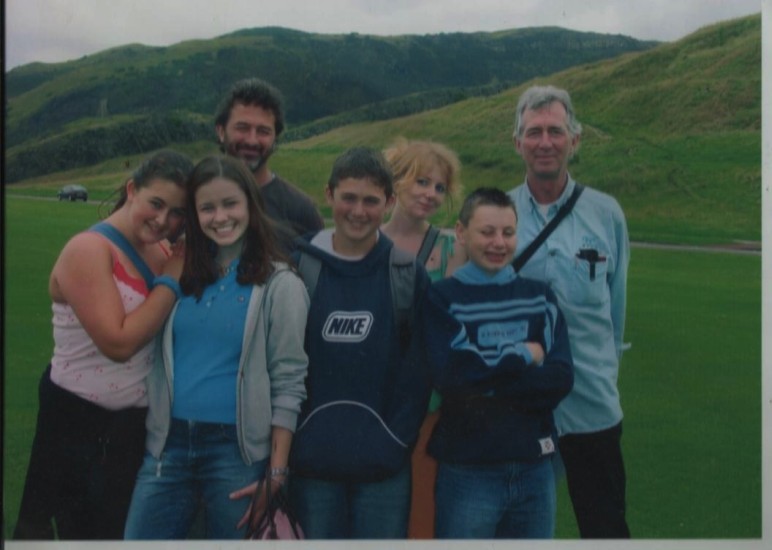

Lynch with his family at Edinburgh’s Salisbury Crags at Hollyrood Park in 2005. From left to right: Lynch’s daughter, Sophia; niece Kim; Lynch; his son, Walker; his partner, Jules, and her son, Dylan; and Lynch’s brother E.J.

In 2009, Lynch spoke at a Massachusetts grade school and told the story of Sister Elizabeth of Blessed Sacrament School in Jamaica Plain, the only teacher he had who would “encourage a proper, liberating, creative approach to writing.” A serious boy came up to Lynch after his talk, handed him this paper origami nun, and said, “I thought you should have a nun. Her name is Sister Elizabeth.” Sister Elizabeth hangs in Lynch’s car to this day.