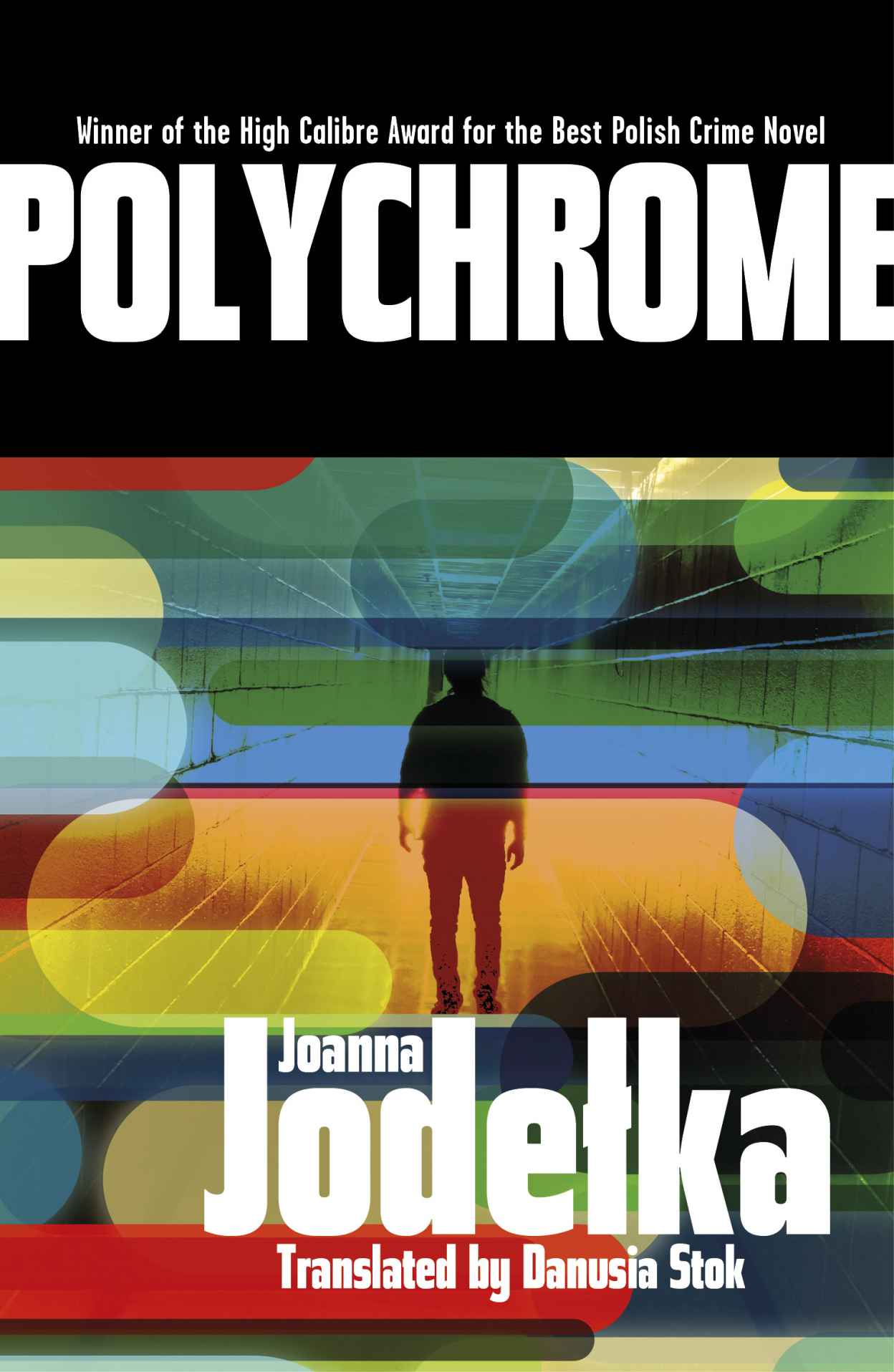

Polychrome

Authors: Joanna Jodelka

polychrome

a crime of many colours

by Joanna Jodełka

translated by Danusia Stok

Published by

Stork Press Ltd

170 Lymington Avenue

London

N22 6JG

English edition first published 2013 by Stork Press

1

Translated from the original

Polichromia

© Joanna Jodełka, 2009

English translation © Danusia Stok, 2013

Institute in London for its support towards the publication of this book.

The moral right of the author has been asserted

These characters are fictional and any resemblance to any persons living

or dead is entirely coincidental

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic,

mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written

permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book

ebook ISBN 978-0-9573912-4-6

Designed and typeset by Mark Stevens in 10.5 on 13 pt Athelas Regular

Printed in the UK

To Professor Konstanty Kalinowski

Dear Professor, you were right…

November

that year was more like November than ever.

Ugliness in all its splendour – as if for show – proud.

Not only had the leaves already managed to fall, they

had also managed to blend in with the surroundings, dance

with the mud and start the slow process of decaying. Besides,

everything had begun to look as if it had decided to disintegrate

more vilely than usual.

At least that’s what the inhabitants of Great Moczanowo

thought and felt.

Evidently the filth they’d once chased away from their village

had now returned, since this is where it had come from; they

sensed it in the air and beneath their feet again, everywhere;

just as they felt everywhere the unimaginable crime which had

taken place here and would remain here forever.

They hid and wanted to believe that it was the wind, heavy with

rain, and not the ever-present shame which crushed them to the

ground, bowed their heads and didn’t allow them to go out without

reason. Did not allow them to gabble, gossip, grumble either in

the shop, on the streets or anywhere. They spoke so quietly they

barely heard themselves speak, and the dogs, chained to their

kennels, barked less; or maybe that’s just what everyone thought.

They were afraid of punishment. Punishment for everything

which, barely a month ago, had painted leaves and life in

fiery colour.

But what a knot of activity it had been at the time. Everywhere,

in homes and by fences, in front of the shop and even by the

church – although there a little muted. Half of the sentences had

begun with ‘apparently’, and every detail – carried, so it seemed,

by a still summery, warm breeze – had circulated lazily round

the neighbourhood, there and back, provoking smiles and joyful

spite cut through with a touch of outrage, as if a comma.

People had sighed, rolled their eyes, pulled faces – openly,

with satisfaction. A well-known and valued formality. Of

course, the prophetic ‘it’s all going to end badly’ had nearly

always cropped up, but only as part of the ritual, like an ellipsis

without great significance. Because, when it came out into the

open, all hell was going to break loose…

Later, contrary to the norm, nobody had said ‘and didn’t

I say so’, even the stupidest of peasant women. Because what

would that have meant?

For many more years to come, when – out of sheer curiosity

– those working at regional administration were asked about it,

they mumbled something which was a little unclear and with

apparent shame, both the firm believers in God and those who

only went to church on special occasions. United as never before.

If then, some thirty years ago, a stranger had by some

miracle stopped in the village, he would probably have thought

it a touch more sleepy, a touch more depressing, but apart

from that much like any other ‘ordinary God-forsaken hole’.

He wouldn’t have discovered that this was precisely what the

people thought of themselves, terrified that God had forgotten

about them, or wishing He would forget. That if they didn’t talk

about it, nobody would ask, ever.

But God was on the side of the pessimists again; He was

obviously partial to them in these parts. Or perhaps He had

good reason.

Because they clearly weren’t afraid of Him.

Because it had been a priest – His servant a killer.

Because evil had been conceived.

Such things not even the people forget.

ANtoNIusz mIkulskI

– retired restorer of monuments and

buildings – didn’t have to get out of bed to see the old apple

tree wither outside his window. He didn’t feel sorry; the tree

was no longer any use. It hadn’t produced any fruit for a long

time and when it had the apples had been maggoty and sour.

He thought the same about himself.

Maciej Bartol – commissioner in the Poznań police – had already

been awake for several minutes. He felt the day was going to be

a scorcher. He wondered whether his ex-girlfriend was going to

wear the floral dress today, the one whose straps slipped down so

readily. He didn’t open his eyes; he didn’t want her to disappear.

Romana Zalewska – architect – picked up the telephone while

still nearly asleep, spoke briefly but to the point, as though

she were in the office and not in her own bed, naked. She’d

mastered the art to perfection. Fifteen seconds later her head

was nestling in her pillow again, free of guilt; she had, after all,

worked late into the night.

Edmund Wieczorek – retired postman – had been awake for two

hours. He didn’t want to miss the two students who’d recently

moved in on the first floor when they returned. They’d come

home at dawn, as usual – not alone. He liked them; they were

the only unpredictable cog in the monotonous life of those

living in the tenement on Matejko Street. There was something

to see.

Krystyna Bończak – mother of two boys – was making up another

parcel. The prison on Młynarska Street, again. Cigarettes, yet

again. She’d prayed and cried through the night, again. She’d

fallen asleep in the early hours of the morning and woken up

in the morning; still, she was happy the day had already begun.

Everything appeared different in the day.

The man in strange glasses was putting on a new shirt. He was

pleased: he’d just managed to fasten the cuffs – good, they

wouldn’t reveal his wrists. He approached the window which

never opened, and looked out at Warsaw from the height of the

thirtieth floor. There was nothing to see during the day.

Ksawery Rudzik – real estate agent – woke up earlier than usual

and much earlier than needed. He didn’t like and, on principle,

didn’t tolerate wallowing in bed; he’d simply open his eyes and

get up. Always, but not this time. He hadn’t treated himself to

a night in one of the most expensive hotels in Warsaw only to

leap out of bed. He was bursting with pride.

As if to reinforce it, he stretched languidly and with pleasure.

Only five years ago everything had been different. He’d failed

his bar exams for the second time; as usual it was the sons

of high-fliers who’d got in but he was nobody’s son and very

much wanted to change this. Five years of law, five years of hard

slog, rotten food and jars from his mother – good but somehow

shameful, five years of hope that everything would change, that

he’d be able to go to restaurants, dinners and so on.

It had seemed unlikely. It had seemed unlikely even when,

for lack of money, he’d started working for a real estate agency,

something which he hadn’t boasted about too much initially.

Until it had become clear, both to him and his employer,

that he was damn good at it. Complications didn’t put him

off – impoverished, greedy beneficiaries who quibbled over

unassigned shares in a tenement; couples which, with a

flush on their cheeks, had only recently acquired credit for

their dream apartment but were now at each other’s throats,

pulling out their dirty linen and justifying their unjustifiable

reasons; opinionated landlords and fussy tenants – he liked

all this. He’d stand between them with the expression of one

who knew more, who’d solved harder cases. With superiority

but also kind-hearted understanding which for years he’d

rehearsed in front of a mirror. Law was also proving very useful:

magic articles, incomprehensible paragraphs, an appropriately

concerned expression seasoned with a loud, sympathetic sigh

in the case of taxes, a couple of sentences on the tardiness of

courts and cases ‘like these’ going on for years. All this, thrown

in at the right moment, worked wonders.

Yesterday, he’d passed the state exam as a real estate agent.

He was one of no more than a few lucky ones. The milieu was

closing in: he knew that and it suited him. Why let in new

blood? There were enough people there already, the rising

economy was not going to last forever, one had to prepare for

worse times. He smiled with contentment as he looked down

at Warsaw from on high, from a good position.

He wondered a little longer whether to phone Kasia but

decided against it. He would have to swap her, too, in the end.

A pleasant girl, pretty enough – and he did love her in his own

way – but she didn’t suit his perfect world. He remembered her

showing him the beautiful handbag she’d bought at a bargain

price. He’d praised the hideous string object curtly.

He couldn’t understand why she didn’t notice how it made

him sick, how he now hated those cut-price joys, those beautiful

cheap handbags and shoes, how he loved the big, ostentatious,

brazen golden logos of good brands, how he’d always loved them.

Another visitor also appeared, unwanted in this place, at

this moment. His mother. He wasn’t going to call her either.

The endearment in her voice annoyed him, telling him to look

after himself, dress warmly, avoid draughts, and that accent of

hers, the turn of phrase which reminded him of where he came

from. His lousy surname was enough. His first name wasn’t too

bad; it could have been much worse – his other grandfather

had been called Szczepan.

He quickly chased away any scruples for not visiting his

mother, for spending as much on one night in the hotel as

would last her a month.

Neither of them understood how little time he had to become

someone, that shortly everything would stabilize, that the door to

the world he wanted would close soon and everyone would live

in pre-determined positions, that he had to hurry, that he could

run around tower blocks in sensible shoes and rent apartments

to students, but that he had to have shoes which wore down and

an expression which showed it didn’t matter.

He pondered a little longer, donned a carefully chosen

shirt, smiled at the man of success he saw in the mirror and

went downstairs for breakfast. He picked a good table (he saw

everyone and everyone saw him), helped himself to a small

portion of ham and vegetables, not too much; he’d already seen

people at various receptions with plates loaded because the

food came free. He even tempted himself to a little extravagance

in the form of a fruit salad.

He began the ceremony of relishing the moment, the

breakfast and himself – everything was excellent. He just felt he

was investing too much energy in the difficult art of appearing

natural in a situation which was unnatural to him.

Thoughts about whether he was acting naturally started to

grow in strength and could have ended with him spilling coffee

and treacherously revealing his natural defects. Fortunately,

the man at the next table caught his eye.

He liked to evaluate people; it had become his passion of

late, and the accuracy of his judgement had increased his bank

account.

The man couldn’t have been much older than him; it was

only the glasses that added gravitas. They were a bit strange –

dark lenses too pale for a pair of sunglasses and yet too dark for

corrective lenses; besides, the frames were also neither here nor

there, neither old nor new. The dark blond hair had perhaps been

well cut three months ago but had now been forgotten about and

rested messily on the collar of a boring, grey shirt unfastened

to reveal a cord with a gold pendant. The man looked a bit too

ordinary to be a guest at a five-star hotel, nor was he a tourist who’d

strayed from his group, even less so a sales representative. Most

importantly, he was acting naturally. This, Ksawery could sense

perfectly well, although he couldn’t explain how he’d arrived at

the conclusion. The man under observation wasn’t interested

in his surroundings. He wasn’t eating breakfast, or smelling the

warm bread rolls; he wasn’t starting his day on a pleasant note,

wasn’t smiling. He was behaving as if he’d found himself at a

petrol station and was filling up with the fuel necessary for life,

no more. This was how a man behaved eating breakfast standing

up at a train station, but not here, thought Ksawery.

It didn’t give him any peace. If, for example, the man had

entered his office, he, Ksawery, would have raised his eyes

from the computer but only for a moment, and immediately

pretended he was very busy. He rebuked himself for such

thoughts – he had to be careful, had to be alert, the man might

be a philosopher but one who had inherited a tenement from

his parents, he’d heard of such cases. One could always learn

something and he, Ksawery, learned even at moments such as

these. As a counter-balance, he praised himself.

He must have watched the stranger for too long because

the latter tore his eyes away from his plate, met Ksawery’s gaze

and without a moment’s hesitation bowed in greeting. Ksawery,

caught staring, was at first unable to do anything. He didn’t

get another chance, however, because the stranger calmly

continued to eat without looking at him.

And he, too, didn’t turn his head in the man’s direction.

He wasn’t proud of himself but quickly found a satisfactory

explanation for the awkward situation – a foreigner; our

kinsmen always turned their eyes away and pretend to look in

the opposite direction.

After breakfast, he walked past reception, asked for his bill

to be made ready and a taxi to the airport to be ordered. He

knew that the nice woman didn’t need any information as to

where the taxi was to take him, but it had sounded good and

she’d smiled differently somehow; this he’d also rehearsed. He

was learning how to make an impression and was improving.

The taxi was of better quality, too – a Mercedes with a neat,

tidy and polite driver. Ksawery calmly arrived at the airport,

didn’t hurry and wore the expression of a man who is not in a

hurry. The airplane was even delayed according to plan. Ksawery

was sure that he was the only passenger in the departure lounge

pleased with the delay and it wasn’t at all because he’d barely

arrived on time himself. He decided to go to the bar but still

couldn’t decide whether to grumble a little or order a drink with

a large quantity of ice. He didn’t decide; he didn’t have time.