Pox (39 page)

Authors: Michael Willrich

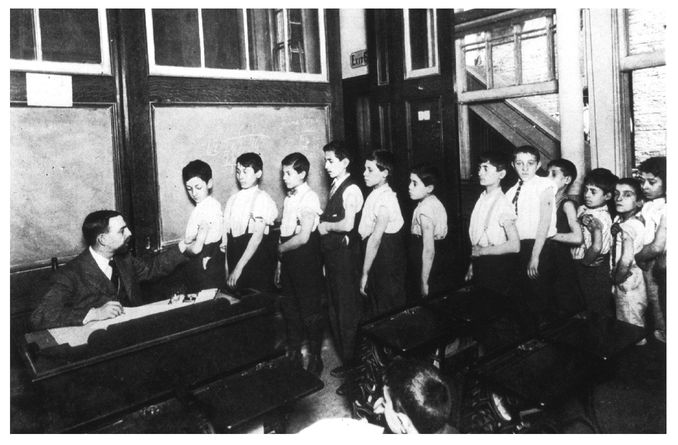

New York City schoolboys line up to have their vaccination marks inspected by a public health officer in 1913.

COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL LIBRARY OF MEDICINE

Â

Mass vaccinations at American workplaces generated their own dynamics of power and conflict. American workers were vulnerable not only to contagion but to arbitrary dismissal during epidemics. Domestic employers, fearing exposure to infection, shunned servants and laundresses, causing destitution in the tenements. When smallpox broke out, some factory owners abruptly suspended operations, with no thought of compensating their workers for lost wages. In a typical incident in Sayreville, New Jersey, two handkerchief manufacturers, acting upon the advice of physicians, told their employees to stay home until the local epidemic was brought under control. The order affected about three hundred workers, many of them the breadwinners of their families. Workers pleaded with foremen. One factory girl dropped to her knees and prayed. All to no avail. To employers and local health officials, the mere threat of smallpox justified the most overt acts of ethnic scapegoating. When a single Italian worker with smallpox escaped from quarantine in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, in 1902, Bethlehem Steel Company summarily discharged all of its Italian workers. Italians were forbidden to ride the city streetcars until the outbreak subsided .

47

47

Employers normally bristled at workplace health regulations. Key pieces of progressive labor legislationâincluding factory safety measures and laws to shorten the workdayâwere justified by reformers as necessary to protect the health of workers and the public. Manufacturers' associations and individual employers challenged such measures in the courts, insisting they violated the “liberty of contract” between worker and employer. But when faced with the potentially expensive emergency of a smallpox epidemic that had a relatively cheap solution (vaccination), many industrial employers readily cooperated with public health officials. They willingly turned their private workplaces into public health stations.

48

48

Many employers made vaccine refusal grounds for dismissal. In one 1901 episode, six Brooklyn health department physicians, policemen in tow, appeared at the sugar refineries of Havemeyer & Elder, just in time for payday. As each worker stepped forward to receive his wages, a city doctor vaccinated him. Railroad and streetcar corporations, liable for damages if an employee with smallpox infected a passenger, were particularly vigilant. In the winter of 1903, as smallpox raged in the Pennsylvania coal region, officials of the H. C. Frick Coke Company, a vast industrial enterprise of coal mines and coke works, ordered all of its employees

and

their families to get vaccinated. According to the

Chicago Tribune

, the order affected 300,000 men, women, and children.

49

and

their families to get vaccinated. According to the

Chicago Tribune

, the order affected 300,000 men, women, and children.

49

When employers joined forces with local health officers and police to enforce vaccination, a crowded factory floor could become as confining as a prison. In April 1901, a female worker at the American Tobacco Company in Passaic, New Jersey, died of smallpox. She had continued to work during the early contagious stages of her disease. In such an instance, any responsible employer would want to secure the safety of his workplace by assuring that the workers got vaccinated. But the measures taken at the American Tobacco Company went well beyond that duty. A squad of government physicians and police entered the plant, determined to vaccinate all 350 women and girls who worked there. Informed they would have to submit to vaccination, some workers fainted, “others became hysterical, and there was a general rebellion,”

The New York Times

reported. Two hundred of the women tried to escape, but they found all of the factory exits locked. “[A]ll were finally vaccinated.”

50

The New York Times

reported. Two hundred of the women tried to escape, but they found all of the factory exits locked. “[A]ll were finally vaccinated.”

50

As C. P. Wertenbaker observed time and again in the South, workers' natural fears of vaccination were intensified by their need to earn. Many American industrial workers feared, with good reason, that vaccine would cause their arms to swell, making it impossible for them to support themselves or their families for a period of days or weeks. And they knew better than to expect their bosses or the state to support them during that period of disability. Some washed off vaccine (as Martin Friedrich spied workmen doing at an Ohio factory). Others walked off job sites rather than be vaccinated. African American workers, in particular, dreaded vaccination. In June 1900, the New York State Board of Health ordered the vaccination of five hundred black workers at the Wash & Company brickyard in Stockport, New York, about thirty miles down the Hudson from Albany. According to

The New York Times

, when fifty of the laborers “refused to submit,” Governor Theodore Roosevelt sent in the Hudson Company of the state militia, “ninety men strong,” to enforce vaccination against the “unruly negroes.”

51

The New York Times

, when fifty of the laborers “refused to submit,” Governor Theodore Roosevelt sent in the Hudson Company of the state militia, “ninety men strong,” to enforce vaccination against the “unruly negroes.”

51

Violence was always a possibility when health officials clashed with American workers. In 1902, smallpox struck the neighboring mining cities of Lead and Deadwood, in the Black Hills of South Dakota. Both cities ordered a general vaccination, but the miners balked. The city physician of Leadâaccompanied by four assistants, the sheriff, and five deputiesâconducted a nighttime raid of the city's crowded saloons, gambling dens, and theaters. At the Gold Mine Saloon, the officers covered both entrances and proceeded to vaccinate everyone in the place. Several fights broke out, but eventually the police overwhelmed the miners.

52

52

Controlling smallpox on the nation's vast network of railroads was obviously a crucial step to stamping out the American epidemics. But how? In the winter of 1902, Chicago health officials announced a Chicago-sized plan. The Second City stood at the hub of the nation's transportation networks. The same central geographical position that made Chicago such an economic forceâbringing grain, lumber, and livestock from the rural hinterland to American markets and sending Montgomery Ward catalogues back in the other directionâmade the city vulnerable to smallpox outbreaks all over the Middle West. In January 1902, about 10,000 cases of smallpoxâroughly three fourths of all reported cases in the United Statesâoccurred within a few hours' train ride from Chicago. The Chicago Health Department decided to use the Second City's position as the railroad hub of the Middle West to stamp out smallpox in a ten-state region with 25 million inhabitants. City health officials made an agreement with officials of the major companies serving Chicago to spur “wholesale vaccination and revaccination in every infected locality” of the region by enforcing a strict inspection of all travelers from those communities. The railroads also ordered all of their employees serving the Chicago routes to submit to vaccination or lose their jobs. And every car entering the city from any direction had to be fumigated for six hours before new passengers were allowed to enter it.

53

53

Â

Â

A

cross the American political landscape, public ambivalence about compulsory vaccination during the turn-of-the-century epidemics registered in the statute books. Mississippi, one of the states hardest hit by virulent smallpox in 1900 and 1901, enacted a new law authorizing county boards to order compulsory vaccination (which many refused to do). Rhode Island passed a new law in 1902 that mandated vaccination of all children before their second birthday and empowered the state board of health to order vaccination of all “inmates of hotels, manufacturing establishments, hospitals, asylums, and correctional institutions.” That same year, Massachusetts gave local health boards authority to compel vaccination at will.

54

cross the American political landscape, public ambivalence about compulsory vaccination during the turn-of-the-century epidemics registered in the statute books. Mississippi, one of the states hardest hit by virulent smallpox in 1900 and 1901, enacted a new law authorizing county boards to order compulsory vaccination (which many refused to do). Rhode Island passed a new law in 1902 that mandated vaccination of all children before their second birthday and empowered the state board of health to order vaccination of all “inmates of hotels, manufacturing establishments, hospitals, asylums, and correctional institutions.” That same year, Massachusetts gave local health boards authority to compel vaccination at will.

54

Other states, though, moved the other way. Wisconsin governor Robert M. La Follette vetoed a new compulsion statute in 1901, insisting (as the

Journal of the American Medical Association

remarked with disbelief) that “he does not believe an emergency exists which demands a law repugnant to so many good citizens!” In Utah that same year, grassroots opposition to compulsory public school vaccination spurred the legislature to pass a law banning compulsion. The

Wasatch Wave

applauded the statute: “it robs the tyrant of his power to rob the people of their right to âlife, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.' ” And two years later, well-organized antivaccination activists in Minnesota persuaded the legislature to forbid compulsion in the absence of an actual smallpox emergency.

55

Journal of the American Medical Association

remarked with disbelief) that “he does not believe an emergency exists which demands a law repugnant to so many good citizens!” In Utah that same year, grassroots opposition to compulsory public school vaccination spurred the legislature to pass a law banning compulsion. The

Wasatch Wave

applauded the statute: “it robs the tyrant of his power to rob the people of their right to âlife, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.' ” And two years later, well-organized antivaccination activists in Minnesota persuaded the legislature to forbid compulsion in the absence of an actual smallpox emergency.

55

New York lawmakers debated a compulsory vaccination bill in 1902. The state had long banned unvaccinated children from the public schools. But beyond that the legislature had not ventured, prompting

The New York Times

to assert, “compulsory vaccination is a thing utterly unknown in this State.” In February 1902, State Senator James McCabe, a physician from Brooklyn, introduced a bill that would have been one of America's strongest vaccination laws. It required cities to enforce universal vaccination whenever the health department called for it. Any resident who refused vaccination was subject to a $50 fine and imprisonment for ten days. Companies with more than ten employees were forbidden to hire anyone not vaccinated within the past five years. The New York County Medical Association championed the measure. So did the

Times

. Remarkably, the New York City Board of Health opposed the bill. The city's new health commissioner, Dr. Ernst J. Lederle, explained that the legislation would simply hand the city's antivaccination leagues a tool for recruitment. Compulsion was unnecessary, Lederle insisted. His department had encountered “no serious difficulty . . . in persuading the people to submit to vaccination.” The bill died in the New York Assembly.

56

The New York Times

to assert, “compulsory vaccination is a thing utterly unknown in this State.” In February 1902, State Senator James McCabe, a physician from Brooklyn, introduced a bill that would have been one of America's strongest vaccination laws. It required cities to enforce universal vaccination whenever the health department called for it. Any resident who refused vaccination was subject to a $50 fine and imprisonment for ten days. Companies with more than ten employees were forbidden to hire anyone not vaccinated within the past five years. The New York County Medical Association championed the measure. So did the

Times

. Remarkably, the New York City Board of Health opposed the bill. The city's new health commissioner, Dr. Ernst J. Lederle, explained that the legislation would simply hand the city's antivaccination leagues a tool for recruitment. Compulsion was unnecessary, Lederle insisted. His department had encountered “no serious difficulty . . . in persuading the people to submit to vaccination.” The bill died in the New York Assembly.

56

Residents of New York Cityâat least those who lived in the tenements or read the daily papersâmust have found Ernst Lederle's public position on compulsion baffling. A Ph.D.-bearing chemist, Lederle had taken office in January 1902, appointed by the city's new reform mayor Seth Low to head up both the board of health (which promulgated health regulations for the city) and the department (which carried them out). High on the list of disgraceful conditions that Low's administration promised to eradicate was smallpox, which had continued to spread despite the aggressive tactics of Alonzo Blauvelt's vaccination corps. Nearly 2,000 cases, with 410 deaths, had been reported in the city's five boroughs in 1901, making this New York's worst smallpox epidemic since 1881.

57

57

For Lederle, smallpox was the most interesting problem confronting a modern department whose activities covered everything from making vaccine to policing milk dealers to arresting the spitters who spread the city's deadliest endemic disease, tuberculosis. Smallpox concentrated Lederle's mind on the larger purpose of his office: to extend the benefits of modern medicine to the city's “great tenement populationâill-housed, illnourished, bred in the foul air of the slums; above all, ignorant of the laws of cleanliness and right living, and willing to go to any lengths to hide the evidence of disease from the municipal physicians.” Tellingly, Lederle expressed admiration for the work of the U.S. Army Medical Department in Havana, “a striking example of what can be done in a short time.”

58

58

Under Lederle, the health department managed compulsion well enough without a law that would have strengthened the political base of antivaccinationists and given Albany a greater hand in the affairs of local health departments. Lederle publicly denied that coercive legal power was necessary, even as his department routinely exercised just such power in the city's tight spaces. Lederle added more than 150 new men to the vaccination corps. By the end of his first year in office the department performed a record-breaking 810,000 vaccinationsâmore than twice as many as in any previous year. The commissioner sent letters to the owners of all the city's larger factories, offering them the services of a vaccination squad, at any hour of the day or night. His board of health ordered lodging houses to refuse shelter for more than one night to anyone who failed to provide proof of recent vaccination. Discovery of a pimple-faced passenger aboard a trolley in the Bronx in March 1902 was sufficient cause to reroute the train, with all the passengers aboard, to the nearest police station, where a city health officer got busy with lancet and virus. “Those who objected were sternly admonished and the work went on.” The following month, James Butler, a hostler, and his wife, Kate, living on the third floor of a Third Avenue tenement in Harlem, were discovered “suffering from smallpox in an advanced stage.” A vaccination squad arrived, backed by twenty police officers. Men, women, and children fled down fire escapes or climbed to the roof. “But policemen were at hand at every place of egress, and appeals and entreaties were unheeded,” the

Times

reported. By the raid's end, 300 residents had been vaccinated, “the majority of them very much against their will.” James Butler was found hiding in a coal bin. After a struggle, he and Kate were taken to North Brother Island.

59

Times

reported. By the raid's end, 300 residents had been vaccinated, “the majority of them very much against their will.” James Butler was found hiding in a coal bin. After a struggle, he and Kate were taken to North Brother Island.

59

Other books

Nightlord: Shadows by Garon Whited

Nauti Dreams by Lora Leigh

Killing Cassidy by Jeanne M. Dams

Our One Common Country by James B. Conroy

Cocaine by Hillgate, Jack

The Unwritten Rule by Elizabeth Scott

What Doesn't Kill You by Virginia DeBerry

The Chameleon Fallacy (Big Bamboo Book 2) by Norwood, Shane

[Texas Rangers 05] - Texas Vendetta by Elmer Kelton

The Best of All Possible Worlds by Karen Lord