Practical Genius (10 page)

Authors: Gina Amaro Rudan,Kevin Carroll

Now you’re at that special place where the cultivation of your personal power begins. It’s not enough to know where your other G-spot lives; you have to get out there and do something with it. We start by giving your genius a voice and a story. Keep reading.

FRANCESCA PRADO

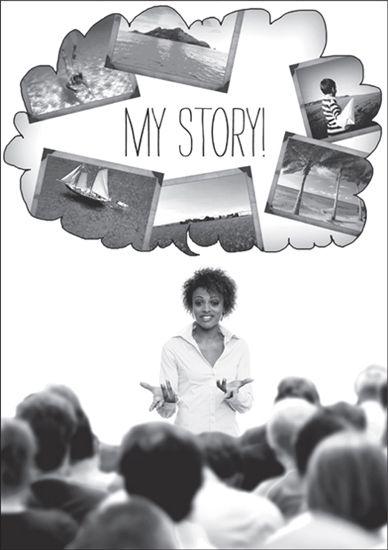

It’s Time to Tell Your Story

One of the great benefits of being a human being (as opposed to being an emu, for instance) is the endless ways we have to express ourselves. Lucky us. Language, music, art, dance—we don’t have to say a thing, but we can give expression to a whole wide world of truth, experience, and feelings. The more evolved the species, the more sophisticated the means of expression—or so the story goes.

In fact, whereas animals use every expressive tool in their toolbox (screeches and howls, glances and gestures, touch and chase) for practical reasons of survival, we human beings are notorious for ignoring most of our expressive capabilities, choosing instead to use a few of the simplest tools (or blunt objects) even at the risk of spending a lifetime being misunderstood or unappreciated.

Let me be clear: this is not an option for the practical genius.

Living as a practical genius requires that you use all the tools at your disposal—every letter of the alphabet, every color, every note,

every shape and texture of the human experience—to give expression to your genius. If you can’t express it, it might as well not be there.

I think that generally folks believe that if they are reasonably communicative and attempt to make themselves clear, they’re doing a good job of expressing themselves to others. But I’m here to tell you that what you’re doing now isn’t enough. The good news: I can teach you another way to express yourself, and I can show you how to turn your self-expression into a genius asset of tremendous proportions.

To begin with, what comes out of your mouth is only a small fraction of what you communicate to others. The expression on your face, what you’re wearing, the way you carry your body, even which seat you choose at a conference table tells people something about you. You actually express yourself all day long, although I’d guess you rarely do it with a particular purpose, and you certainly don’t tell the whole story.

That’s what it is, you know—a story. There’s a story you’re telling about yourself as you move through the world. It may not be the story you mean to tell. And even if it’s the story you’d choose for yourself, I guarantee you’re not telling it as well as you should.

I have a friend who goes to parties and always says to people she’s just met, “Nice to meet you. So what’s your story?” She says people almost never know where to start their story, usually falling back on how they know the host of the party or what they do for a living. That’s not a story! That’s a wasted opportunity to express your genius.

When I ask you, “What’s your story?,” I want your answer to make me understand your narrative; I want to hear the vocabulary and themes that reflect your values; and I want to see your “illustrations,” the visual expressions of the genius of you. Like me, the people you work with, play with, and live with

want

to know your story. We want to hear it every time we interact with

you, because it conveys your authenticity and helps to increase the value and meaning of our relationship over time. Yet how much do we leave out of our stories? How much do we leave on the table or never leverage in our relationships because we’re not telling our genius story?

In this chapter, I’m going to take you through a step-by-step process of identifying and telling your own compelling story. You’ll learn how to find your unique narrative, identify a few salient themes, illustrate that story with rich details, and share it all with people in a brief two minutes or less. But first I want to explain

why

it’s so important for every practical genius to have his or her own story ready to share.

Remember the 1984 children’s film,

The Neverending Story?

It was based on a German fantasy novel about a young boy’s quest to save Fantasia, a land without boundaries that was created by the dreams and hopes of mankind. Fantasia was slowly dying as people lost their imaginations and ability to dream to an emptiness and despair that were referred to as the “Nothing.”

“People who have no hopes are easy to control,” said the servant to the power behind the Nothing. That quote has remained with me since I first heard it at the age of twelve. I think that today many of us are unconsciously falling under the power of the Nothing, abdicating our imaginations and courage to dream and hope and tell our whole stories in the real world. Expressing genius is expressing your hopeful self, the intuitive self that leads with vigorous curiosity. Are you battling the Nothing in your work, seeing just glimmers of your hope only on weekends, when you’re free to imagine? Are you surrounded by people who are part of the Nothing, who ignore their own imaginations and don’t care about their stories?

Consider how the Nothing has taken over many of the folks you work with. Many professionals walk the halls of organizations in a numb state, robotic in their behavior, believing that sharing their soft assets is “inappropriate.” Well, I think censoring creative abilities, values, and passions in the workplace is inappropriate and has contributed to the spreading of the Nothing in many organizations, both big and small.

The Nothing is a powerful analogy to help keep you accountable to a personal form of expression of a contributing, gifting nature. Expressing your genius is a personal quest to vanquish the Nothing. It’s about ensuring that the meaning and value of your story are constantly being conveyed, to the benefit of both yourself and others. But first you have to know what your story is.

If your practical genius is the place where your hard and soft assets intersect, the single most important way you leverage that sweet spot is by telling your story. I don’t mean a stiff little biography of yourself like this: “My name is Anne, I grew up in the Midwest, now live in Atlanta and work as finance director with Widget Inc. I have two kids, and in my spare time I enjoy my book club.” No offense, Anne, but I am neither enchanted by your story nor convinced of your genius. This sorry, one-dimensional elevator pitch just doesn’t cut it. I want a story that shows me something true about you. When you think about your story, I want you to ask yourself what that story

looks

like. For that matter, what does it sound like, feel like, and taste like? It needs to have that much texture. So let’s dig in.

Take an ordinary day in your life. Have you ever really listened to yourself? What’s the internal narrative of your day? What’s the game plan you lay out in the locker room (the bathroom, your car)? What are the thought balloons, the notes to self you make throughout the

day? How often do you use your internal narrative to prepare for an important meeting?

Expressing your practical genius is not about expressing the limitedness of our personalities or egos but more about expressing wonder of the depths of the oceans of who we are as complex multidimensional creatures. Certainly all of those pieces of information Anne shared above are true. But what if she adapted that flat profile with some of the texture and topography of who she

really

is—say, a cheerful atheist married to an Episcopal priest. Or the Scripps Howard National Spelling Bee champion of 1989. Or a breeder of Rhodesian Ridgebacks. Those aren’t details Anne would fling randomly to the wind. They are pieces of the story of her that she should learn how to tell—and that I would

much

rather hear because she just might be a genius I want to know!

Here’s your challenge: Take a whole day to note all the instances and ways you tell your story—if at all. What are the signals you send in your ordinary exchanges with people? Is there anything consistent about the way you project yourself to those who populate your day? Do you convey an energy, a sense of contribution, or connections with others that are a reflection of you are across all of your communications? When you e-mail or tweet or update your profiles on any one of a number of digital venues, are you purposefully telling your story—or are you just regurgitating empty bits of information that have no meaning and steal time from you and everyone who reads about you?

Here’s a stunning reality: you have only two minutes to get someone to care about you. That’s it. The all-time two-minute drill. That means you don’t have the luxury of indulging in small talk or gossip or gripey nonsense when you engage with people every day—whether you know them or not. So if you waste your two minutes on sports or the weather or even your kids (God bless them), you’ve burned through your currency with that person and you should not expect to get another chance to impress your truly valuable, authentic story on him or her again. Game over.

When I train executives to express their genius, the first exercise I ask them to do is to go up to someone they don’t know and make that person care about them in two minutes. You would be shocked to see how many highly trained, exquisitely educated, massively accomplished managers and executives stumble through this conversation. Often they have no idea how to initiate a conversation of substance and meaning. They have no concept of the story they need to tell and less of a sense of what the other person needs or wants to hear. Trust me—this is painful to watch.

During a corporate training session on expressing practical genius, a senior vice president whom I will call Mark decided to hold on to his resistance and play it safe. He chose to talk about football and the life-shattering disappointment he had felt when his team lost the previous weekend. What didn’t register with Mark was that the young manager he was speaking with had committed entirely to the exercise and had shared with Mark the fact that he was adopted as a child. The manager found Mark’s lack of sincerity and inability to open up a trust buster and a turnoff. Mark told the wrong story, people.

There’s a moment in this exercise when the discomfort begins to diminish because some of the natural storytellers come to the surface. Some tell childhood stories; other share short stories of triumph or funny stories or stories with a pulsing heart the other person is powerless to ignore.

I love this exercise. After everyone is done, I ask the participants to identify the best stories they have heard, and this inevitably leads to an active discussion that reveals that many have worked for years

together but have never heard the others’ stories. This exercise can be liberating for many, but also a wake-up call to how powerful your story can be if you really know what your story is and know how to tell it.

One of my favorites was told by an architect who was trying his two-minute drill on me. “Have you ever slept outdoors?” he began, to which I responded “Not in many years.” He proceeded to share that he’d been looking for a way to get a better understanding of the environment in his own neighborhood for a green project he was working on. So he decided to camp out in his urban backyard for ten days, pretty much just to see if he could do it. To his surprise, he learned a great deal from his experience, a real treasure trove of insights and impressions that completely changed his approach to his concept for his green project. For example, his greatest takeaway from the experience was that the design of the project should not only be green but create functional outdoor workspace. His story was short, simple, and beautifully visual, leaving a picture of the type of man I felt quite certain he was. I especially loved how his story revealed the connection between his authenticity (who he is) and his capacity (what he is capable of doing).

Hard-asset types often tell résumé/job interview kinds of stories or play it safe with small talk, which is just that—small in its impact. I don’t know who exactly started the “small-talk standard” of expressing oneself in insignificant ways—entertaining small topics such as the weather, sports, or traffic—but I find it unacceptable. In fact, I believe small talk and the shallowness that comes with it create more boundaries and contribute to numbness of expression, one of the contributing factors to why so few of us have the meaningful conversations we should be having on a daily basis.