Practically Perfect (29 page)

Read Practically Perfect Online

Authors: Dale Brawn

Then consider that the man who intends to commit murder chooses secrecy, silence, darkness. What secrecy was there in the conduct of the prisoner? In broad daylight, in one of the principal streets of the most populous city of the Province he takes a coachman off the stand, drives to a hotel, there takes up this woman, then drives out in the Lake in view of the whole country. If this was a preparation for murder the annals of the world present no parallels to this act, nor could any one present, in his wildest day dreams, have imagined anything so preposterous as that he should thus, in broad day, have gone to commit such a crime in the light of that sun which at the instant should have been darkened. Good God! it is incredible.

If he wished to commit this murder why did he not do it when they were together in the States. In a large city like Boston there were many opportunities. They were strangers in a strange land. No one knew him or her. Completely under his control, as she was said to be, what was there to prevent his dragging her into a place suited for such a deed, and then committing it under cover of darkness. If her body were afterwards found no one would know her.… why at least did he not make some attempt at concealment? Why did he not get a buggy as he might have done and take her up at some street corner and drive her to the place where he meant to perpetrate this deed? But he did not do this. Did you ever hear anything like this?

[11]

Ultimately, the emotional appeal of Munroe’s lawyer fell on deaf ears, and after deliberating less than two hours jurors returned a verdict of guilty. There was only one option available to Justice Allan, and he told Munroe that he would have until February 15, 1870, to prepare himself to die. That is precisely what the convicted killer did. In the days immediately preceding his execution he came to accept the inevitability of what was to come, and spent his daylight hours either in prayer, or in conversation with his spiritual advisers. The night before he was to hang, no doubt at their request, he confessed to the two murders.

The first time I went out with Miss Vail it was only for a ride. We had no quarrel and our going was at her wish. We got out of the coach, at or near the place described on the trial, she had a satchel, and we walked along the road, I cannot say how far, sat down, and had a bite to eat. We both fired at a mark, she using a pistol I had given her — one of a pair — a breech loader, same as my own. The mate I gave to a friend. I had learned her to use it. There was no intention on my part to harm her at that time. We came back and I left her at Lake’s. She was to have gone to Boston on the Thursday after our first going out, but it was too stormy, and I went with my wife to Fredericton on that day, and came down again on Friday night. It was during that trip to Fredericton I first thought that the spot I had visited with Miss Vail on the Monday previous was a suitable spot to commit a bad act. I went out again with Miss Vail the Saturday following. We went the same road as before and to about the same place.

The morning was frosty, the moss crisp and hard. There was no wet on the barren. The road was a little muddy. We went off the road a little way together and sat down. I went into the bushes, the child cried, I came out again, was angry, and strangled the child. I do not know if it was actually dead. As she was rising up, I shot [Miss Vail] in the head — I do not think on the same side as shown in the court. I threw a bush over her face and some over her hands. I found the pistol in her pocket, or just fallen out of it, a common handkerchief and a wallet with only a few dollars in it. I threw the handkerchief and wallet away and left at once and have never been back since. I had previously had some of her money — cannot say how much — perhaps half or a little more. I cannot say that money was not one of the reasons of the motives for the act committed. I do not say it was in self defence I killed Miss Vail. It was the money, my anger with her at the time and my bad thoughts on and after the trip to Fredericton working together, caused me to do the bad act. The letter written to Mrs. Crear [Maggie’s sister] was written by me, and mailed in Boston by a friend of mine living in or near Boston. I never killed any other person or child.

[12]

The day of Munroe’s execution a local paper spoke of the deep sadness enveloping the city. “Today a funeral pall hangs over our city; this a morning of sorrow — deep ineffimable sorrow. The crime of murder — murder the most cold-blooded, brutal and abhorrent — has been expiated by the life of the perpetrator.… Oh! May Munroe’s ignominious death, act as a warning to seekers of illicit pleasure, and other degrading vices, turning them back into paths of uprightness and honor.”

[13]

Munroe woke on the fifteenth about 4:00 a.m., and dressed himself in dark pants, a white shirt, and boots. Never well-off, all he had to leave his wife was a gold watch and chain, and he asked his jailors to ensure that his widow received them. At 7:45 a.m. three things happened almost simultaneously. The executioner who was to hang Munroe entered the condemned man’s cell and pinioned his arms to his side; a bell began tolling a notice of the impending execution; and a black flag was raised over the jail. Before Munroe left his cell his hangman placed a white cloth hood over his head, and pulled it down until it rested on the architect’s nose. When all was in readiness, the procession of sheriff’s officers, spiritual advisers, hangman, and killer started out. As they walked to the gallows everyone, including the guards who lined the corridor, joined in singing

Rock of Ages

.

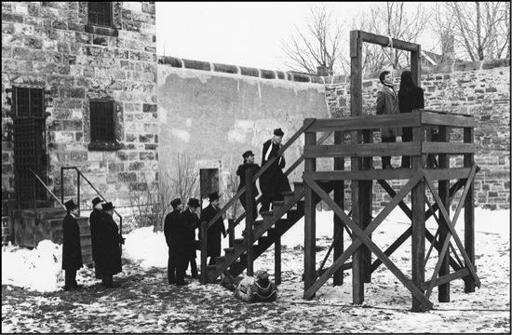

Typical execution carried out in the courtyard of a Canadian jail. When executions were carried out in jail, courtyard scaffolds were usually constructed as close to the jail as possible, so that a condemned prisoner would have little time to panic after seeing for the first time the instrument of death that was about to take her or his life.

Typical execution carried out in the courtyard of a Canadian jail. When executions were carried out in jail, courtyard scaffolds were usually constructed as close to the jail as possible, so that a condemned prisoner would have little time to panic after seeing for the first time the instrument of death that was about to take her or his life.

Courtesy of Peel Art Gallery, Museum and Archives.

The scaffold Munroe saw as he stepped from the jail into the courtyard was quite unlike the structure most closely associated with official hangings. This one consisted of a single tall post, to which a long beam was fastened with a swivel. The noose, which was to be placed around Munroe’s neck, was attached to one end of the beam, and the other end of the rope ran along it and through the back door of the jail, where it suspended a weight of several hundred pounds a few feet off the ground. As soon as he was told to proceed, the hangman cut the rope holding the weight. When it dropped, the end of the beam to which Munroe was attached swung up, jerking the condemned man into the air. The force of gravity eventually caused his body to fall back towards the ground, and Munroe’s neck received a second jerk before he was left dangling two feet over the platform. It was not a pretty sight, and things soon got worse. “For a moment there was no motion save the swaying of the body, then the hands began to work, the fingers clutching and then closing with a grip. The legs were not drawn up, but by muscular contraction were turned over across the other somewhat. The neck was evidently not broken, death resulting from strangulation.”

[14]

Twenty minutes later the man who very nearly got away with two murders was dead.

Maurice Ryan: Bones of a Brother

It seemed that no matter how hard Maurice Ryan tried, he was always his own worst enemy. Nothing he did turned out right, and certainly not the murder of his brother. In the waning years of the first decade of the twentieth century the Ryans were notorious in the North Bay area of northern Ontario. Francis Joseph was the more high profile of the brothers, and the brothel he operated was one of the region’s better known pleasure palaces. Maurice, on the other hand, was a regular in the town’s bars and gambling dens. Neither was the type of man who could be trusted. And that was what cost Francis his life.

In many frontier communities like North Bay houses of ill repute were a fact of life. Although not formally part of the established order, they were nonetheless tolerated, provided those who ran them kept a low profile. That was something Francis simply could not do. On November 5, 1907, the authorities finally decided to bring him to account, and charged him with keeping what locals referred to as “a house of ill-fame.” But for Francis, going to jail was not an option, and rather than stay around to answer to the charge, he decided he leave town. With his brother in tow, he closed his account at the Ottawa Bank and withdrew his substantial savings, rented a horse and buggy for the trip to the train station, then headed home to pack his bags. While he was there he told the attractive young woman who managed his business that he was leaving for the United States, and after settling his affairs in North Bay he would be back to pay her what she was owed. Around 9:00 p.m. he did just that, and in the process displayed a huge wad of money.

The last anyone saw of Francis, he was sitting beside his brother as the two drove from town towards the train station at nearby Callander. The next morning Maurice returned the rented buggy and claimed he had no idea where the blood came from that was plainly visible all over the wagon and on the suitcase, which Francis apparently forgot to take with him when he got on the train.

For the next few days Maurice was seen everywhere. First he showed up at his brother’s former place of business, claiming to have purchased the contents of the house, which he promptly sold to the brothel’s new operator. He then headed to his favourite bar, where he paid his tab with bills peeled from a roll of cash surprisingly large for a man previously dependent on the goodwill of others. Asked where the money came from, Maurice said he won it playing poker. Next came a trip back to the livery stable, where Ryan repaid money borrowed from the owner. Apparently worried that he was getting a little low on funds, Maurice showed up at the Traders Bank, and cashed a cheque drawn on an account of his brother’s New York bank.

Over the next few weeks Maurice spent time just about everywhere people drank, and when asked about his brother, always responded that Francis was well, and the two were in regular contact. That response may have satisfied strangers, but it did nothing but raise a suspicion in the mind of James, a third Ryan sibling. When he last saw his absent brother, Francis was looking forward to getting out of town and promised to get in touch once he settled somewhere in the United States. Of course, James did not actually expect Francis to write, since he knew his brother was illiterate. You can imagine his surprise, then, when he received not one, but two letters, the first mailed from Vermont, and the second from Ottawa. Although in each the writer claimed to be Francis, James recognized the handwriting. The letters were written by his sister.

Almost exactly a year after Francis was last seen alive a homesteader clearing land eight miles from North Bay literally stumbled across a skeleton lying in bush, about sixty feet off a road. The remains were under two trees, which fell when the area was burned over some months earlier. Although the fire destroyed what was left of the corpse, when investigators removed the bones, they found beneath them a bullet, a watch, and a tag bearing the name “Francis Joseph Ryan.”

As soon as Ontario Provincial Police officers knew the identity of the dead man, they were convinced that Maurice killed his brother, and he was promptly arrested. Making matters worse for the black sheep of the Ryan family was the fact that two weeks before Francis went missing Maurice threatened to kill him. Things became heated when Francis refused to lend his brother $5. To get even, Maurice threatened to tell his mother that Francis was keeping a bawdy house. That, he told everyone within listening distance, would kill her, “and I will kill him.”

[15]

In late March 1909, Maurice went on trial for murder. The proceedings were a formality. Witness after witness testified that just about everything Maurice did following the disappearance of Francis made them suspicious that something was amiss. Even the alibi Maurice offered investigators did not hold up. The accused killer said he was not the person who drove his brother to the train station the night he disappeared. The driver, he said, was James Driscoll. When Driscoll was called to the stand he brought with him a copy of his work record, which proved beyond a shadow of a doubt that in the months before and after the killing he was nowhere near North Bay.

Because Maurice did not testify at his trial, all his lawyer could do was suggest to jurors that his client should not be convicted because (a) the Crown failed to show that Francis was dead, and (b) the Crown failed even to prove that the skeleton discovered in the bush was that of a man. Neither of the arguments did anything to change the minds of jurors, and twenty-five minutes after they began deliberating they returned to court with their verdict. A little over two months later Maurice paid the price for his crime.

June 3, 1909, dawned bright and beautiful in North Bay, and it was a day of great promise, for everyone except Maurice Ryan. He spent the previous evening in quiet conversation with his spiritual adviser, taking time to converse with a few of the newspaper reporters on hand to witness his execution.