Priestess of the Fire Temple (2 page)

Read Priestess of the Fire Temple Online

Authors: Ellen Evert Hopman

Tags: #Pagan, #Cristaidi, #Druid, #Druidry, #Celt, #Indo-European, #Princess, #spirituality, #Celtic

The Characters

AÃfe (aee-fah):

former ard-rÃgain of In Medon

Aislinn (AHSH-linye):

from

Aisling

, a supernatural dream or vision, a ban-Drui and the narrator of this tale

Alda (AHL-thuh):

a Drui from Murthracht, spouse of Cainleog

Alvinn (AHL- vin):

a warrior in Aislinn's retinue

Amlaim (OW-leev):

a Drui from Irardacht

Ana (AH-nuh):

Aislinn's birth mother

AoibhgreÃne (EEV-grey-nyuh):

“ray of sunshine”; a nickname given to Aislinn by her teachers

Artrach O'Ruadán (ARD-rukh oh ROO-uh-thawn):

a Drui from the Forest School of In Medon

Bárid (BAW-rith):

a Drui from Irardacht

Barra Mac Mel (BAR-ruh MAHK MYEL):

father of Aislinn, ard-ri of In Medon

Birog (BIH-rog):

a healer from the tuath near the Fire Temple

Bláth (blawth):

“flower”; Aislinn's white mare

Bláthnait (BLAWTH-nij):

a female Drui from Torcrad

Breachnat (BREKH-nud):

concubine of Ãobar

BrÃg Ambue (BREEGH um-MOO-uh):

a teacher of law at Cell Daro

BrÃg Brigu (BREEGH BREE-ghuh):

senior ban-Drui of Cell Daro

Cainleog (KAN-lyog):

a Drui from Murthracht, spouse of Alda

Canair (KAHN-ir):

a female Drui from Torcrad

Caoilfhionn (KWEEL-in):

a student of Dálach-gaes and Niamh

Carmac (KAR-vak):

a Drui from Oirthir

Caur (kowr):

“warrior, hero”; Alvinn's warhorse

Conláed (KON-leyth):

the household bard of Ãobar's dun

Coreven (KOR-even):

a warrior in Aislinn's retinue

Crithid (KREE-thith):

gatekeeper at the Fire Temple

Dálach-gaes (DAW-lukh GWEYS):

fili to the court of Aislinn's father

Deaglán Mac Ãobar (DYEG-lawn MAHK-EE-ver):

prince of Irardacht

Deg (dyegh):

a student of Dálach-gaes and Niamh

Dunlaing (DUN-ling):

a Drui from Oirthir

Eógan (YO-ghun):

brother of Aislinn

Ergan (ar-ghan):

a child of Dálach-gaes and Niamh

Father Cassius:

a Greek priest, abbot of In Medon

Father Cearbhall (KYER-wal):

priest to the court of Ãobar

Father Justan:

a monk from Armorica, originally from Inissi Leuca (Gaulish, “island of light”)

Fer FÃ (FAER-FEE):

Spirit of Yew, the goddess Ãine's dwarf

red-haired brother

Finnlug (fin-lug):

a warrior, son of Canair

Garbhán (GAR-vawn):

a warrior, son of Canair

Imar (IV-ar):

a Drui from Irardacht

Ãobar (EEV-ar):

father of Deaglán, ard-ri of Irardacht

Ita (EE-duh):

a female fili from Torcrad

Lasar (LAS-sar):

“flame”; Coreven's red horse

Lovic (low-vick):

king of a petty kingdom south of Irardacht

Lucius:

former ard-ri of In Medon

Nessa (neh-sah):

a ban-Drui of Cell Daro

Niamh (neev):

wife of Dálach-gaes and ban-fili in the court of Aislinn's father

Roin (Row-in):

son of Lovic

RóisÃn (ROSH-een):

nursemaid of Aislinn

Siofra (SHEEF-ruh):

fiance

é

of Eógan

Siobhan (shee-von):

a pregnant woman from the tuath near the Fire Temple

Slaine (SLAW-nyuh):

a child of Dálach-gaes and Niamh

Tuilelaith (twil-uh-lith):

Aislinn's mother, wife of Barra Mac Mel

Ãna (OO-nuh):

a kitchen maid

A Brigit, a ban-dé beannachtach

Tair isna huisciu noiba

A ben inna téora tented tréna

Isin cherdchai

Isin choiriu

Ocus isin chiunn

No-don-cossain

Cossain inna túatha.

O Brighid, blessed goddess

Come into the sacred waters

O woman of the three strong fires

In the forge

In the cauldron

In the head

Protect us

Protect the people.

Invocation of the Goddess Brighid

by Ellen Evert Hopman;

Old Irish translation by Alexei Kondratiev

Prologue

I

hope you don't mind if I call you Sister,” I said to the neophyte priestess, pulling my hand from under the worn goose-down coverlet and gesturing with a finger towards her face. My hand was as light as a newborn chick, its skin so transparent I could easily trace the bones and veins beneath.

She was two generations younger than I, and a slight shock registered on her face as I made the suggestion.

The rains of winter had set in, and a damp breeze seeped through the bare stone walls, guttering the candles and making the hearth-fire dance. My eyes were dimmer than they ever had been, but my body still thrummed with unseen energies.

“Let me tell you how it was,” I declared again firmly, meaning the words as a command.

I was always teaching, ever anxious to pass along the old ways; the gods would not permit me to do otherwise. The girl was charged with my care, and we still had the long season of dark before us and not much entertainment, so it seemed a good time for a tale.

“Certainly, my lady.” She leaned forward to adjust the coverlet over my frail bones as I began my story with an old saying: “

Trà nà is deacair a thuiscint: intleacht na mban, obair na mbeach, teacht agus imeacht na taoide

. Three things hardest to understand: the intellect of women, the work of the bees, the coming and going of the tide.

“That was a favorite saying of the BrÃg Brigu, the one who initiated me into the teachings of the Fire Temple. What I am about to tell you now is a great mystery, and I hope that you will cherish the words⦔

PART ONE

A Spark of Flame

1

I

was but fourteen years old and had not yet reached the end of my growing, and I could still wend my way around the warriors unseen if I kept my head down and minded the mud. The ladies were always too preoccupied to notice me; they were busy comparing their hairstyles, jewels, and dresses. Everyone wore their finest to the

oenach

, the great harvest fair on the grassy sward outside of the high king's rath.

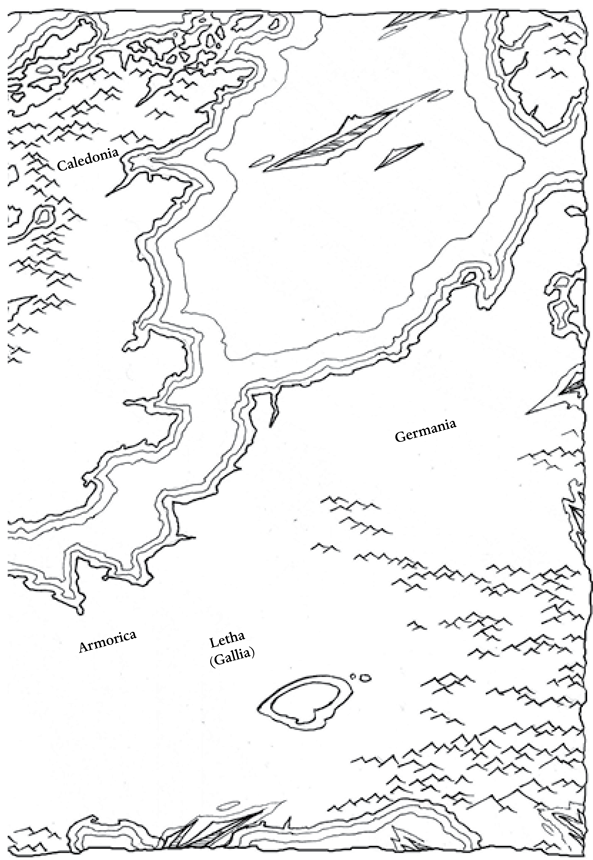

There were a dizzying number of activities at festival time, when the usually quiet lawns outside of the dun were given over to horse-racing, musical and poetry competitions, storytelling, proclamations of new laws and contracts, and a loud marketplace where vendors from all the provinces came to sell their handicrafts and produce. Since it was a royal fair, there were many imported items from the southlands; folks eagerly awaited the arrival of the new styles from Letha and Armorica, foreign kingdoms to the south from which exotic new styles and goods were brought to us by ship and then by great trains of horses and carts.

My father was everywhere, greeting visitors, joining in the fighting competitions, and awarding prizes. My mother, Tuilelaith, was also there, of course, but I hardly saw her. Her time at the oenach was spent absorbing the news of the noble families and cultivating the wives of the flaithâanything to advance my father's interests.

“The quickest way to get a man to do something is by pillow talk,” she would say, for once she had convinced a noble lady of some cause of hers, the lady would take the message home and whisper the queen's desire into her husband's ear at night.

My mother was far too busy for someone as insignificant as me. Summer and winter she was preoccupied with refurbishing the roundhouses of the rath. She loved to commission new furniture and woven hangings for the walls, when she wasn't knocking them down. She liked to expand her dwellingsâ“To let the sun in,” as she would say. Everyone thought she was terribly extravagant, the way she insisted on large window openings covered with thin sheepskins that let in the light. The windows caused a terrible draft and meant that great logs had to be burned in the hearths in every season.

My father indulged her extravagance; in truth, I think he was a little afraid of her. She came from a noble family of Letha and constantly reminded my father that she was somehow superior to him. I don't know why he accepted that so readily, seeing as he was the ard-ri, but he did. He would quench his temper in cups of mid and then take it out the next morning on the warriors at practice rather than confront her. He liked a peaceful household, no matter the cost.

I think my father thought that all women were somehow superior. Or perhaps it was my mother's ankle-length hair the color of winter wheat that held him in its spell. My father's clan were dark haired, and she stood out amongst them like an exotic flower.

As for myself, I was a constant disappointment. My mother would have liked a daughter with carefully plaited hair and trimmed fingernails and eyebrows blushing with the black juice of elderberriesâa daughter she could dress in costly imported silks and furs. Instead she got me.

She did her best to ignore me, as if I were no relation of hers; I think she found me an embarrassment. But she always gave her full attention to my brother, Eógan, who would likely inherit the throne. She liked to oversee his dressing and made sure he had golden earrings and circlets of gold on his arms and fingers whenever he went outside of the rath.

My mother measured out her affections carefully, calculating the potential value of each recipient.

“Only those with a great dun and many cattle are worth knowing,” she would say.

Hidden behind her words was the implication that since I didn't have dun or cattle, I was not yet worthy of her esteem.

The only exceptions to her rules for affection were her cats. She kept a small tribe of them, seeing them as her true children and also as gorgeous works of art.

“See how they always choose the pillow of the exact shade to complement their beauty?” she would remark.

My brother and I hated those cats. I blush to tell you that we would swat them when she wasn't looking. Of course they would run off before we could do any real damage, and in later years I had several cats that were as children to me; some I loved even more than people.

From the time I could walk I delighted in being out of doors, collecting butterfly wings and cristall glain, the white quartz pebbles that the Druid call fairy stones. I thought that if I carried them around with me, sooner or later I would hear a voice or see a fairy. Eventually I did both, of course.

My clothes were ever smeared with dirt and the juice of wild berries. My nurse, RóisÃn, thought it particularly disgraceful that I ate berries from the hedgerows.

“Those belong to the fairies!” she would say with an expression of disgust.

As a child I was passionate about the subject of fairies. As you know, there are many different kinds of fairies to be felt, heard, and seen. Some of them live in trees, some in the water, and others live in great hives underground, led by their fairy queen. Some say they are creatures of fire and air. The Cristaidi say that they are “fallen angels” who tumbled to earth from the sky world called heaven and are now forced to live underground. But I can feel them everywhere.

I learned the many ways to attract the fairies; for example, by their love of shiny objects. My teachers told me to make a habit of carrying cristall glain and also ametis, the purple stone of the fairies, as a way to develop my inner sight. They said that any white stone belonged to the fairies, and I would set out such stones in a tiny circle on the forest floor to draw the fairies to me and bury them in a ring around my fairy altar.

My altar was a simple tree stump surrounded by foxglove and evening primrose flowers. I would pop the evening primrose blossoms and leaves right into my mouth in the summer and harvest the roots and seeds in the fall. The roots were simmered and eaten with butter; the seeds were sprinkled on porridge or added to bread dough. My teachers said that they were an aid to developing the Sight when eaten. But I never ate the foxglove leaves or flowers, becauseâas you knowâthat plant is a powerful medicine that will poison those who disrespect it or use it without knowledge.

It is said that the fairies gave that plant to the foxes so they would have little gloves on their feet to hunt silently.

My teachers were very insistent that the fairies and the land spirits had to be kept happy in order for the animals, crops, and tribes to prosper. I would pocket bits of bread and cheese for them at supper and bring sweets to my fairy altar on feast days. The mogae and free farmers showed respect for the good folk in their own way; every garden and field had a small corner set aside for their exclusive enjoyment, where no human would dare to tread.

I learned that the fairies love music of any kind. Often I would sit by a tree or pond and play my wooden flute for them. I had a bell branch too, nine tinkling bells affixed to an ash wand. Sometimes I would walk through the woods just shaking the branch for their pleasure.

At times I could hear them singing in a perfect three-part harmony in their own ancient language. I noticed that if I sang a song for them or if the household bard was outside singing, the fairies would quickly pick up the tune and weave it into a complicated harmony for their own enjoyment. I concluded that their singing was what caused the plants and trees to grow; it was as if they were weaving the forests, fields, and gardens into being with their songs.

I was especially thrilled when I found a fairy ring, a circle of mushrooms growing on the grass or on the forest floor. When I found one I would dance around the circle counterclockwise, because moving in that direction dissolves the barriers between the worlds. Sometimes I would step right into the ring, but I always leapt out quickly, because everyone knows that if you linger inside a fairy ring, you might be taken for seven years.

I learned that where oak and ash and hawthorn grow together is a good place to find fairies. Other such places are where two streams meet and at the edge of a pond or lake. Waterfalls and the black shoreâthe edge of sand between the line of seaweed and the seaâare all liminal places that are “betwixt and between” and thus likely spots for fairy sightings.

Dusk and dawn are the best times of day to encounter them, because those times are between night and daylight, neither one nor the other. I could always sense the fairies' presence because a sudden smell of flowers would envelop me. That was how I knew they were near.

My teachers gave me a holey stone, one that they had found by the sea, with a natural hole in it. They taught me to gaze through it to see the past and future and the land of the fairies. They also taught me to meditate and to focus on my third eye, the point of energy between my brows, and then slightly open my eyes. That was a great aid to seeing the fairies and other spirits.

One reason I finally learned to love my mother's cats was because I was taught to follow them around and sit where they sat. There was a stretch of lawn outside my mother's roundhouse that was surrounded by fruit trees and flowers. It seemed a very peaceful place, and Tuilelaith would often go there to sit on a wooden bench in the sun to calm herself after a trying day at court.

One time I followed a white cat out onto the lawn and noticed where she sat. When the cat got up to leave, I sat down in the exact same spot, facing the same direction the cat had faced. Much to my surprise I could feel intense activity all around me, even though there were no people or animals to be seen. When I closed my eyes and then reopened them just a bit, I clearly saw four golden pathways stretching in front, behind, and to the sides of me. I sensed that I was sitting at the crossroads of a busy fairy highway, and I could even see the evidence of tiny footsteps in the grass. Yet when I opened my eyes wide and focused on the grass, there was nothing there.

There was a whole other class of creature that lived inside of our roundhouses and barns. The dairy maids were forever weaving little wreaths of milkwort, butterwort, dandelion, or marigold, and binding them with a cord of ivy or red thread, placing them under the milk pails to prevent the milk from being stolen by the fairies or charmed away by evil spirits. And they never failed to pour a bit of each day's first milking onto the brownie stone near the barn. It was well known that the failure to make the milk offering would result in sickness for the cattle.

In the kitchens the cooks would bank and smoor the fires at night and then leave the bread dough to rise on the warm stones of the hearth. Usually the dough would have risen by morning, but if it didn't they would blame the fairies. Sometimes things in the kitchen kept disappearing and then reappearing in the most unlikely places. Then the cooks would have to make offerings at their own fairy altar, a small wooden affair hidden in a corner of the kitchen, to placate the house spirits.

I hope that I do not bore you when I tell you these things. Because they are the same things that everyone learns about the spirit realmâpart of every person's basic education.

Mainly I was taught by the Druid to have great respect for the land spirits and the fairies, to develop my relationship with them and to do everything in my power to keep them happy. But I would never mention them in the presence of the Cristaidi for fear of causing offense. In Cristaidi times the fairies were not to be spoken of, as if they no longer existed. But everyone knew they were still there.

My nurse, RóisÃn, was short, plump, and very proper. She had no children of her own and as a result was devoted to me with a deep and abiding love. Her léine and tunic were always covered with a neat white apron that she would change if she ever got a spot on it, and she was forever handing her shoes to the mogae so they could scrape off the mud. Her hair was braided into two tight brown coils and always pinned neatly behind her ears.

She said that the wild berries I was always picking belonged to the fairies. Somehow the berries growing in the carefully tended gardens inside the rath were the only acceptable fare, and then only if handed to me on a plate.

My own red hair hung loose down my shoulders, and I almost never stopped to look at my reflection in a burnished metal scathán or I, too, might have been shamed by my looks.

Unbeknownst to me, the day of my fourteenth oenach was to be something very different. RóisÃn found me in the byre that was reserved for the sick cows, and I remember that a huge bullock was hanging upside down over a pit while men were doing something to its hooves. I was fascinated by the spectacle, and I am sure I was ankle-deep in straw and manure because I recall that RóisÃn screamed out loud when she saw me. She pulled me out of the byre and shoved me towards my sleeping house, loudly ordering a hot bath and clean clothes from the mogae.

Once she had me scrubbed, dried, and scented with lavender, she selected a léine and tunic the color of sky and sea, with a matching wool shoulder cloak that she said complemented my hair, and helped me dress. When she had my hair plaited and golden ornaments tied onto the braids (she always made tight braids that hurtâthe reason I wanted to wear my hair loose), she shoved me roughly against a wall.

“You have to get married! This is no time for you to be wandering into cow sheds and around the countryside like a beggar. Your father wishes to speak with you about it this evening, before the feast!” Her fingers jabbed into my shoulder for emphasis as she uttered each word.

I recall that I was speechless. RóisÃn had never been that rough with me, and the whole concept was so foreign that I did not know how to frame my thoughts. I thought marriage was only for great ladies like my mother, never for the likes of me. I hadn't even begun to bleed yet. I knew I wasn't ready.