Prime Time (17 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

So just do it! Stay vigorously and aerobically active!

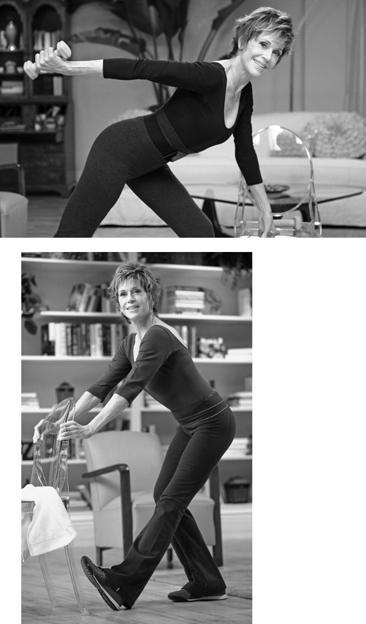

I was 72 and was doing my first workout DVD for boomers and seniors after twenty years out of the business.

Watch it Now Entertainment

Aerobics and Your Brain

“Perhaps the most direct route to a fit mind is through a fit body,”

3

says Jane Brody, the wonderful health writer for the

New York Times.

All brain experts will tell you that physical activity will do more for your brain health than the expensive computer-based brain games that are so much the rage these days. (Although Dr. Michael Hewitt, at Canyon Ranch, suggests that doing both might be the smartest move of all!)

Obviously, aerobic fitness helps the brain by reducing the risk of heart attack and stroke. But it also improves cognitive functioning by slowing the age-related shrinkage of the frontal cortex of the brain, which is where “executive functions” like reasoning and problem solving take place.

In a 2007

New York Times

op-ed piece, Dr. Sandra Aamodt, a freelance science writer and former editor in chief of

Nature Neuroscience,

and Dr. Sam Wang, an associate professor of neuroscience at Princeton University, wrote, “Exercise causes the release of growth factors, proteins that increase the number of connections between neurons, and the birth of neurons in the hippocampus,” which is the seat of memory and where Alzheimer’s disease starts. Reports show that as many as fifty million older Americans may get Alzheimer’s by midcentury. While research is under way to prevent or postpone the disease, scientists already know, as Jane Brody writes, that “people who exercise regularly in midlife are one-third as likely to develop Alzheimer’s in their 70s. Even those who start exercising in their 60s cut their risk of dementia in half.”

4

A decline in cognitive functioning has long been seen as a “typical” part of aging, but it is not normal. New brain science now shows that seniors who have remained fit and who continue to exercise continue to have good brain functioning.

Earlier I mentioned how aerobic exercise releases endorphins, brain chemicals that give relief from pain, enhance the immune system, reduce stress, and bring us a sense of well-being. Some people need only ten minutes of moderate exercise to experience the endorphin rush; others might require thirty minutes. The effect is often called a “runner’s high,” and it is one reason why physical activity is increasingly becoming part of the prescription for the treatment of depression and anxiety—a beautiful side effect of exercise that motivates many of us to keep doing it.

What About Weight-Training Exercise

for People over Fifty?

Weight lifting—or resistance training, as it’s sometimes called—is great for people over fifty, even essential! While it doesn’t increase your endurance the way aerobic exercise does, it does maintain or increase the size and strength of your muscles, and there are several reasons why this is important at any age.

For one thing, increasing your muscle mass helps you lose weight, because muscles are the active tissues in the body. They determine your basal (or resting) metabolism rate, the rate at which your body burns caloric energy. Muscle tissue turns your body into a calorie-burning machine even when you’re resting.

We tend to put on weight as we get older. This is due partly to our tendency to be less active while continuing to eat the way we always have. But it is also due to the fact that we lose, on average, 3 to 5 percent of our muscle tissue each decade after age thirty. This means that by the time we reach seventy-five, our resting metabolism (basal metabolism) will have dropped by about 10 percent—unless, of course, we become active enough to maintain our muscles. In either case, we should also consciously eat fewer (but more nutrient-rich) calories.

Here’s a dramatic example of what can happen: If you eat just one hundred calories more than you burn up every day, you can expect to gain more than fifty pounds in five years. In order to lose this fat, you have to burn it up as a source of energy. (That is, if the calories you eat are fewer than the number of calories you are burning as energy, then the additional energy you need will have to come from stored fat.) To sum up: Aerobic or fat-burning types of activities will help with weight loss, as will increasing your resting metabolism rate through weight-training or resistance exercise to maintain your muscle mass. According to research done at Tufts University on people fifty to seventy-two years old, muscle mass can actually be increased by more than 200 percent with exercise.

Weight Training and Your Bones

Lifting weights or doing resistance training with elastic resistance straps or tubing will not only maintain or increase your muscle mass, it will also improve the strength of your bones, which, in turn, will reduce your risk of osteopenia and osteoporosis, the loss of bone mineral density.

The Tufts study that reported increased muscle mass in older people through resistance training also reported that bone mass can similarly be increased. This is important because osteopenia and the more advanced condition osteoporosis put us at greater risk of fractures, especially of the hip, wrist, ankle, and spine. There are more than 250,000 hip fractures in the United States every year, 80 percent of them to women, and, in 10 to 15 percent of older people, these fractures can lead to death. Something else that is increasingly important with age is the fact that strong muscles can reduce stress on the joints.

Weight Training and Your Brain

Researchers in British Columbia found that women who did an hour or two of weight training every week had better cognitive function than those who did only balance and toning exercises. After one year, the women who lifted weights scored higher in the ability to make decisions, resolve conflicts, and stay focused.

5

As Dr. Michael Hewitt, the research director for exercise science at Canyon Ranch Health Resort, says, “Looking better and being stronger are wonderful, but functioning better is life-enhancing!”

Some Specifics on How to Do Weight Training

If you want shorter workouts, you can work one set of muscles on one day—say, your upper body—and target a different set the following day—in this example, your lower body. Or instead of spreading your weight workouts over several days, you can do a longer, full-body workout three times a week; even two times is beneficial.

For muscles to become stronger they have to be stressed enough to cause overload or cellular fatigue, after which they need forty-eight hours to recover. This is why you should never work the same muscles on consecutive days. However, because of the nature of abdominal muscles, they can be worked every day!

I recommend doing two sets of twelve to fifteen repetitions for each muscle group: abdominals, chest, shoulders, back, arms, legs, and so forth. (See

Appendix II

for a chart of the muscle groups.) If you need to use lighter weights because of uncontrolled blood pressure or joint health, make up for it by doing more repetitions.

Keeping our quadriceps muscles (on the fronts of the thighs) strong is so important now because those are the muscles we use (together with our gluteal, or buttocks, muscles) to get up from a chair, or into and out of a car. But muscles come in pairs: the quadriceps (front of the thighs) and the hamstrings (back of the thighs), for instance; the triceps (back of the upper arms) and the biceps (front of the upper arms). To have a balanced body that is less injury-prone, it’s important to exercise both sets equally. When we lift weights to strengthen our biceps, we should also work the triceps. Exercising the large quadriceps muscles should be balanced with exercising the hamstring muscles, and so forth.

Posture

It’s critical, especially now, to pay attention to your posture when you’re working out. If you are in the wrong position, you have a greater risk of injuring yourself than when you were younger. This is why it is a good investment to spend some time with a certified professional trainer—not some gung-ho, push-to-the-limit sort, but one who is knowledgeable about older bodies and knows what to look out for and when to correct you. Be certain that in addition to training and certification, your trainer also has a personality and style compatible with yours.

Key 3: A Three-Step Exercise Program

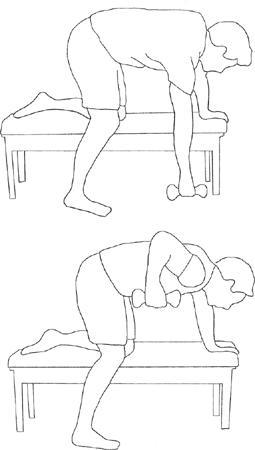

For those of you with very little time, I have included a short, three-step exercise program called Key 3 (see

Figures 1

–

3

), developed by Dr. Michael Hewitt, who, as I have said, is the research director for exercise science at Canyon Ranch Health Resort. These three exercises, done with handheld dumbbells—wall squats, chest presses, and the single-arm row—will challenge 80 to 85 percent of the body’s muscle mass. Dr. Hewitt says that once you get the hang of it, you can complete two sets of the Key 3 exercises in about ten minutes.

6

When it’s this quick and easy, is there any reason not to just do it?

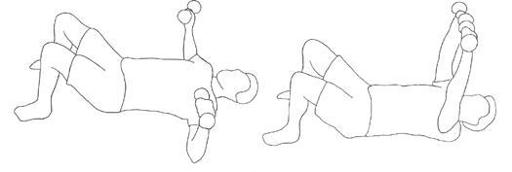

Figure 1. Chest Presses: Lie on your back, knees bent. Hold your dumbbells with elbows bent out to the sides, shoulder height, and bring them together up above your chest.

KAREN WYLIE

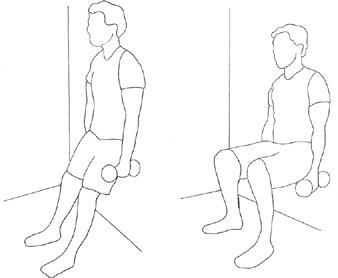

Figure 2. Standing Squats Against a Wall: With feet hip distance apart, hold your dumbbells with arms hanging straight at your sides and squat until your hips are level with your knees—not below your knees! Your feet must be far enough out from the wall that when you squat, your knees are not farther forward than your toes.

KAREN WYLIE