Prime Time (50 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

Except for the chants that preceded and followed the meals, the food was served in silence, in a simple, highly ritualized ceremony in which servers would enter carrying large steaming pots, turn, bow to each of us as it was our turn, and kneel. We would return the bow with our heads and offer our bowl to be filled. As there were three bowls, this process would be repeated three times, each server bringing a different food. We’d been taught at the start exactly how to place our wooden spoon and chopsticks, fold our three cloths (place mat, napkin, and cleaning towel), clean our three bowls, and fold everything back up again. The simplicity and exactitude of the ritualized meals forced me to acknowledge the extent to which I was not, as I had thought, really “in the moment,” paying careful attention to each gesture, each detail. I was spending too much time noticing what others were doing, judging if their napkin was folded into a better lotus-blossom knot than mine. It took several days for me to realize that when I really was in the moment, really showing up, for example, for the small head bows to the servers, I would experience gratitude. “So there is a deeper purpose for each step of the ritual,” I thought.

By day two my back and knees were screaming in pain, and I moved from sitting in a partial lotus on the mat to a folding chair. I told myself that, after all, I was older than most of the others, and that the few who were older than I were also sitting in chairs. Although it never occurred to me to leave—I’m too proud—by day three I was asking myself why I’d come, why I was purposefully putting myself through this torture. What made it all possible—no, not possible; endlessly worth it—were the daily one-hour dharma talks given by Joan or one of the three other priests. “Dharma” refers to the teachings of the Buddha, and because this was a

sesshin

focusing on the enlightenment of the Buddha, the talks centered on enlightenment. We would carry our mats into a semicircle around the priests. They would sit on mats facing us as they talked, and it wasn’t just the breaking of the endless silence that made their words so precious. Sometimes Joan would choose a koan, a brief Zen story that can be understood only when you let go of the mind and allow the

feeling

of it to penetrate you. I was reminded of the twenty-one sayings or puzzles attributed to Jesus in the Gospel of Thomas. He said that grasping their meaning would allow you entrance to the “Kingdom of Heaven”—which I take to mean achieving higher consciousness or wholeness.

Joan would help us understand the koan’s meaning by weaving a personal, often hysterically funny story around it. She told us about the time when she was to give a talk at a big temple in Japan and walked out of the Japanese bathroom, forgetting to take off the bright red toilet shoes (with the word “toilet” written in kanji on the tops of them), and strolled “mindfully” down the public hallway to the lecture hall; her soon-to-be Japanese audience subtly brought her attention to her egregious cultural faux pas. She related this story to illustrate a verse by an ancient Japanese Zen master: “A splendid branch issues from the old plum tree; in time, obstructing thorns flourish everywhere.”

This was a good talk for me, as my lessons in humility were advancing. It seemed like every insight I was having was accompanied by more stupidity and more “thorns.” I was being taught that these obstructing thorns were all part of the package of life.

Every talk Joan and the other priests gave, every story, felt as though it had been chosen especially to help me see why I was there, and what I should reach for within myself. It was comforting when she told us that even the Buddha had had a hard time quieting his “devilish thoughts.” “Whenever an unpleasant state of mind would arrive to the Buddha,” she said, “instead of rejecting it, or judging himself, he would say, ‘Hello, old friend. I know you,’ and that would dispel the state of mind itself. It’s an important strategy, the strategy of nondenial.”

On the sixth day, I noticed that I didn’t have to count my breaths anymore; I was

being breathed,

just as Joan had predicted. The nondenial strategy made my mind less “sticky” and helped me get to a new mind stillness and stay there for minutes at a time. I felt, then, suspended in what seemed like an intersection behind my forehead. Just floating. I was aware that my awareness of not thinking was different than thinking.

Joan describes this as the “nonadhesive mind”; like a mirror, it reflects what is, without judgment or attachment. It’s not something you can make happen. It arises spontaneously. Joan used the metaphor of the mirror and the red balloon: As the red balloon passes the mirror, the mirror reflects the red. It doesn’t judge the red or comment on the red. It just reflects it. But the mirror is not red. It is a clear, still medium (like our minds can be), and thus it can reflect things just as they are, without distorting them with projections or agitation. In other words, I got that it was possible to have an “unfiltered” experience of reality.

During the talks, Joan spoke of what she referred to as nonduality, but I didn’t understand what that meant. Then, on the seventh day, as I was floating in that still void behind my forehead, the sixty people sitting as I was seemed to merge into a single energetic force that filled the hall. It wasn’t that I

thought

of this; it just was. For a fleeting moment I knew that everything—

every thing

—is part of an unbroken wholeness, constantly flowing and coherent. Tears poured down my cheeks. They tickled me. Joan had talked about this—not scratching when we itched, instead becoming the itch. I became my tears. I was beyond happy.

On the final day, we held council. All sixty of us, together with Joan and the other priests, sat in a circle, and each person spoke for a few minutes about what the eight days had meant for us. I learned that every one of us had been challenged in the mind-stilling department. As I heard the others describe their experiences and what had brought them there, all the “loser” labels melted away and all that was left was our shared, beautiful, fragile humanity. The poet Mary Lou Kownacki has written, “Is there anyone we wouldn’t love, if we only knew their story?” I’d been broken open.

It is hard to put words to what the experience at Upaya did to me and for me. But upon my return, I remembered a letter that my grandaunt Millicent Rogers had written to her son Paul prior to her death in 1953—it was he who’d given it to me. Millicent was my mother’s cousin, the daughter of Henry Huttleston Rogers, a cofounder of Standard Oil, and a woman of legendary style. Despite the fact that the Millicent Rogers Museum is in Taos, New Mexico, I had always avoided knowing about her because I wanted to disassociate myself from anything related to my mother and because I assumed Millicent was simply a fancy socialite. How wrong that assumption was! The opening paragraph of her letter showed me that she had attained, before her early death at age fifty-one, what it had taken me seventy years to begin to understand.

Darling Paulie,

Did I ever tell you about the feeling I had a little while ago? Suddenly passing Taos Mountain I felt that I was part of the earth, so that I felt the Sun on my Surface and the rain.

I felt the Stars and the growth of the Moon, under me rivers ran. And against me were the tides. The waters of rain sank into me. And I thought if I stretched out my hands they would be Earth and green would grow from me. And I knew that there was no reason to be lonely, that one was everything, and Death was as easy as the rising sun and as calm and natural—that to be enfolded in Earth was not an end but part of oneself, part of every day and night that we lived, so that being part of the Earth one was never alone. And all fear went out of me—with a great, good stillness and strength.

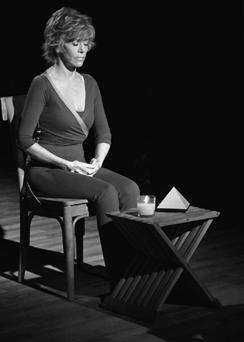

PHOTO BY JUSTIN MARCEL LUBIN

I set the letter down and marveled that I hadn’t read it until my return from Upaya, when I was totally open to her words. I wondered if my ancestor Millicent hadn’t been holding my hand as I’d made my inner journey. Maybe she’s why I have ended up spending so much time in New Mexico. Seekers and sages say that we all have councils of elders guiding us from the other side.

I can’t pretend to carry the non-sticky, non-dual mind with me day to day, but I have begun a regular practice of meditation, and sometimes, when I reach that still intersection, it comes back to me. I can tell from my interactions with people and when I speak publicly that I manifest a different energy, one that encourages an easy give-and-take, often on a soul level—even with strangers. Dr. Laura Carstensen, founding director of the Stanford Center on Longevity, told me that the center is training young students in a Buddhist meditation on death and that the data the staff is collecting seems to indicate that meditation allows the students to experience the “Positivity effect,” similar to what happens to so many people in Act III.

In the days that followed Upaya I was aware of being kinder and more careful of others. Colors appeared more vivid, sounds more acute, and my thinking felt different. Changing your thinking is so hard. Joan had said, “Don’t believe your thoughts.” How to get out from under our thoughts? I learned from Upaya that slowing down the thinking process lets you

feel

beyond or deeper than the thinking process, and thus to avoid being a toy to conceptions. I was to see that this changes the experience of thinking itself.

But the change I noticed most was what happened to time. It seemed to have doubled in volume, and I know why. It is because during the eight days, I had learned to pay deep attention to the Now. This allowed me to see that on a subjective level, time is what we make of it. We’ve all read or been told umpteen times that time expands if we fill it with newness. Remember when you were a child and summer vacation seemed to last a year because things were new? My experience at Upaya showed me that even within the familiar, time expands when we are paying close attention to life, detail by detail, moment by moment. Perhaps this is another purpose of the Third Act. Assuming we are able and want to reduce the to-ing and fro-ing of youth, we have more time to make time for time.

Since my experience at Upaya, I have read books about quantum physics, met scientists, and attended their lectures. I have come to feel that there is a beautiful intersection between the place where meditation leads us, the general falling away of differences that tends to happen with age, and the new physics. It is as if, even before we die (and if we encourage it), we are pulled toward the undefinable totality of flowing energy from which we all emerged and of which we remain a part. It is a place where poetry and science meet. The Vietnamese Buddhist master Thich Nhat Hanh said, “The four elements of space live within my body. When I die, my elements will separate one from the other and return to the mother elements. We are not separate from any being or thing.” The physicist David Bohm wrote, “In a way, techniques of meditation can be looked on as measures which are taken by man to try to reach the immeasurable, i.e., a state of mind in which he ceases to sense a separation between himself and the whole of reality.” Like the teachings of Buddha and Jesus, quantum physics cannot be understood through books alone; it must be experienced—in our body, viscerally. How do you viscerally experience an abstraction like space, infinity, or dark matter? Apparently by transcending the mind. Albert Einstein, for instance, didn’t arrive at his theory of relativity through logic or deduction alone. Many have written about the fact that his theory came to him when he was in a deep, meditative alpha state.

To me, a layperson, it seems to go like this: For a long time, many in science took a mechanistic approach to what constituted the material world, believing that its “ultimate substance” would be found in the building blocks of atoms and even more basic particles, such as electrons, protons, and neutrons. These were thought to be distinct, unchangeable, independent entities. Einstein, with his theory of relativity, challenged the mechanistic understanding of the world. He said that instead of discrete particles, reality was made up of nonlinear, overlapping, ever-changing energy fields. Then scientists discovered that atoms, electrons, protons, and neutrons were not the “ultimate substances” at all, that they were continually transforming into a multitude of increasingly smaller, unstable particles called quarks and partons. Building on this, quantum science has revealed that everything we can see or touch or describe, including space and time, is simply an abstraction of some “unknown and undefinable totality of flowing movement”

1

—including us! How, then, to explain the apparently tangible, solid, visible world of the senses? Physicists see this “manifest” world as projections or abstractions of a higher, multidimensional reality.

To make it easier for us to grasp the concept, David Bohm used the image of a flowing stream: “On this stream, one may see an ever-changing pattern of vortices, ripples, waves, splashes, etc., which evidently have no independent existence as such. Rather they are abstracted from the flowing movement, arising and vanishing in the total process of the flow.”