Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power (10 page)

Read Private Empire: ExxonMobil and American Power Online

Authors: Steve Coll

Tags: #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #bought-and-paid-for, #United States, #Political Aspects, #Business & Economics, #Economics, #Business, #Industries, #Energy, #Government & Business, #Petroleum Industry and Trade, #Corporate Power - United States, #Infrastructure, #Corporate Power, #Big Business - United States, #Petroleum Industry and Trade - Political Aspects - United States, #Exxon Mobil Corporation, #Exxon Corporation, #Big Business

Browne’s announcement galvanized his competitors. “It was as if the industry had been standing by waiting for someone to make the first move; it felt like we had broken a dam,” as he put it.

23

Every North American and European leader of a large oil corporation seemed to conclude simultaneously that his company needed to merge to get bigger. Chevron and Texaco would soon combine, as would Conoco and Phillips, and Total with Petrofina and Elf.

Raymond believed that Exxon was primed for transformational change. As he had taken full control during the mid-1990s, he had concluded that the corporation had a management that could handle a lot more than it was being asked to do. The post

-Valdez

reformers were in place. They had restructured, streamlined, and reduced costs. They were down to “the fine grind,” as he put it to his colleagues. Now what? How could they convert their emerging efficiency into a strategic leap, something that would have global scale?

Around this time, DuPont and Exxon discussed a swap of DuPont’s Conoco oil division for Exxon’s chemical division, but the idea did not ripen. Raymond’s rationale for any proposed merger was not complicated. He ran a resource company. Replacement of resource stocks was fundamental; an acquisition at the right price was a common way for resource companies to replace reserves and grow. It was a part of Exxon’s own history—Standard Oil of New Jersey had grown by acquiring Humble Oil and Refining and other reserve-rich firms. In this case, a big merger might provide a new source of leverage for Raymond to accelerate the drive for efficiency and accountability, the vanquishing of bureaucracy, that he had started after the

Valdez

debacle. It would be the “last brick in the wall of remaking Exxon,” he declared.

24

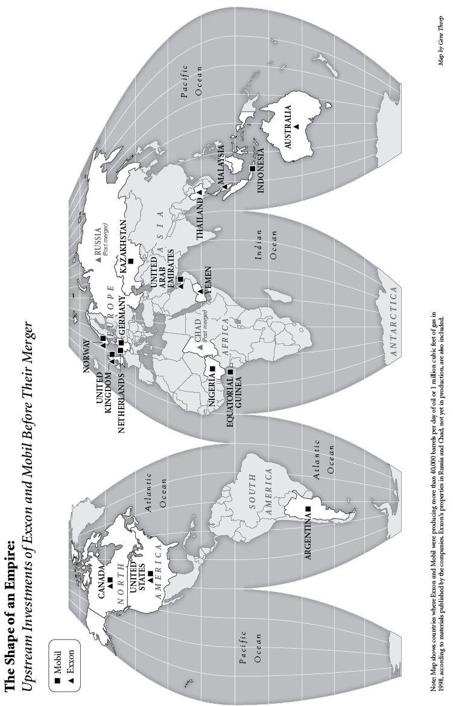

That summer of 1998, Lee Raymond and Lou Noto intensified discussions about a recombination of the baby Standards they each led. There would be antitrust issues in the United States if they proposed a deal, but their lawyers advised them that if they sold off some retail gas stations and perhaps a few refinery properties, the deal should be approved. From Exxon’s perspective, the fit with Mobil was well tailored, particularly because the ends-of-the-earth map of Mobil’s oil reserves complemented Exxon’s more conservative profile, so heavily weighted in North America and Europe. Mobil’s holdings included substantial assets in West Africa, Venezuela, Kazakhstan, and Abu Dhabi. It also held important natural gas positions in Qatar and Indonesia. By purchasing Mobil, Exxon could scale up to compete with state-owned oil giants and leapfrog onto new geographical frontiers.

Exxon had the currency—its own stock—to make such a gargantuan deal without incurring debt or financial risk. During the 1960s, Exxon had handled its cash flow conventionally, paying out most of its earnings as cash dividends. This practice rewarded small shareholders by providing them reliable income. The corporation had about eight hundred thousand such shareholders by the early 1980s. During inflation-menaced 1982, Exxon’s dividend was a hefty 10 percent. The next year, however, Clifton Garvin embarked on a campaign of share “buybacks” as a substitute for some of the spending on dividends. He was advised by Jack Bennett, a finance wizard and mentor to Raymond who left Exxon during the mid-1970s to work at the Treasury Department and then returned to the corporation’s board. He and Garvin concluded that after 1980 global oil prices looked fundamentally unstable. Given the volatility that seemed likely, it would be cheaper for at least a while for Exxon to buy oil and gas reserves by purchasing its own stock than by investing in long-term projects at a high price point. “We had a tremendous amount of cash and no debt, we were convinced that the price structure was unstable, and thus we had no other option,” Raymond recalled, but to buy back shares. Exxon management had long raised cash dividends to beat inflation, but Garvin, and later Rawl and Raymond, were reluctant to raise the dividend too much higher, to match the 5 and 6 percent payouts offered by Shell and British Petroleum, for fear that in a down cycle for oil prices “you can get yourself in a real squeeze on cash,” Raymond said.

25

Each year, therefore, the corporation went into the stock market and used some of the cash generated by its operations to buy its own shares. Between 1983 and 1991, Exxon bought a net total of 518 million shares worth $15.5 billion—a whopping 30 percent of the shares then outstanding.

26

As a result, each remaining share owned by an investor controlled a progressively higher percentage of Exxon’s profits and oil reserves: In 1983, a single Exxon share owned 6.7 barrels of oil and gas equivalents, but at the end of 1989 it owned 8.4 barrels.

During the buybacks, Exxon’s dividend yields fell in relative terms, leaving small shareholders with less cash in their pockets. Did this matter? Arguably, dividend payments and buybacks were equivalent—in one case, a shareholder received cash and in the other, the value of shares rose proportionately. One question was who would make better use of ExxonMobil’s cash, its executives or its dispersed shareholders. By the time he took charge of the corporation, Raymond answered emphatically, “We can.”

Arguably, too, share buybacks could be justified only if the price of Exxon shares at the time of purchase was so low that buying them was a better use of cash than looking for new oil reserves. In the decades to come, however, Exxon would make buybacks continuously, in all price environments, joining an American corporate fashion. Academic studies showed that many corporate leaders had a poor record of buying back shares only when prices were low. “The implied returns . . . from buybacks by big companies would have been laughed out of the boardroom if they had been proposed for investment in bricks and mortar or other more conventional projects,” wrote Richard Lambert, a British critic of the practice.

27

Such programs also raised red flags with some corporate governance specialists because of the manipulations they might mask. Corporate managers might deliberately suppress earnings before a buyback campaign by front-loading expenses to temporarily drive down the price of shares they intended to buy. Repurchases might also smooth out publicly reported earnings per share, to sell Wall Street investors on a story of placid growth when the underlying business was more volatile. In Exxon’s case, all of these concerns hovered, but the buybacks at times also seemed a way to dispose of a problem that other companies could only envy: too much cash.

The shares Exxon bought back did not simply vanish; they were parked in the form of “treasury shares” belonging to the corporation. Raymond and his management team chose to use the parked shares to purchase Mobil tax free. If Exxon could not discover on its own great gobs of oil, it would buy what it could not find: This was an extraordinary payoff for two decades of cash flow discipline.

In late November, Raymond flew on an Exxon Gulfstream IV corporate jet to Augusta, Georgia. The corporation maintained a membership at the Augusta National Golf Club, the site of the annual Masters tournament, and the club hosted an annual Thanksgiving party for families. Raymond typically attended and played golf with his three sons, who had grown into better golfers than he was. This time, Raymond ensconced himself in one of the club’s cabins and played as many rounds as possible while reviewing the final deal terms. Late one night a messenger had to find Raymond’s bungalow to hand over documents.

28

Everyone involved in the deal negotiations, including Lou Noto, knew this would not be a merger of equals. There would be a weighted exchange of shares, but as a practical matter Exxon would take over Mobil. Noto volunteered to accept a subordinate position as vice chairman, reporting to Raymond; he would serve in that role for a transition period and then depart, to enjoy his life in New York.

John Browne later asked Noto if he would have preferred to merge with BP or Exxon. “BP, of course, but I couldn’t make it work,” Noto told him, as Browne recalled it. “When you bought Amoco it was inevitable that Exxon would buy us. It was only a matter of time.” BP had merged its way to a size that Exxon had to match if it wanted to compete, and the acquisition of Mobil was the easiest way for Raymond to get there.

29

On December 1, 1998, Raymond and Noto stood side by side in a J.P. Morgan conference facility in New York to announce their $81 billion deal. There was no mistaking the new company’s hierarchy: Raymond opened the meeting and spoke for twenty straight minutes. He laid out the merger terms, described the prospective business advantages, and announced future plans in bland press-release prose, displaying all the charm of “the proverbial shoe salesman,” as one newspaper reporter covering the announcement put it.

When at last his turn at the microphone arrived, Noto hastened to say that his decision to merge with Exxon was “not a combination based on desperation.”

It was, instead, a requirement of the times. “Competition has changed,” he said. “We’re here because we’re trying to respond to these changes.”

30

ExxonMobil Corporation—the world’s largest nongovernmental producer of oil and natural gas, and soon to become the largest corporation of any kind headquartered in the United States—formally came into existence on December 1, 1999. During its first year of combined operations, the corporation would earn $228 billion in revenue, more than the gross domestic product—the total of all economic activity—of Norway. If its revenue were counted strictly as gross domestic product, the corporation would rank as the twenty-first-largest nation-state in the world. A United Nations analysis, designed to calculate by more subtle measures the relative economic influence of particular companies and nations, concluded that ExxonMobil ranked forty-fifth on the list of the top one hundred economic entities in the world, including national governments, during its first year. Its net profit alone—$17.7 billion that inaugural year—was greater than the gross domestic product of more than one hundred nation-states, from Latvia to Kenya to Jordan. As Lee Raymond told his colleagues, “If we haven’t gotten to ‘economy of scale,’ we’re never going to find it.” He was optimistic. Oil prices were rising again. “It’s a great time to be ExxonMobil,” he declared.”

31

Three

“Is the Earth Really Warming?”

O

n February 8, 2001, nineteen days after George W. Bush’s inauguration as president, ExxonMobil chairman Lee Raymond met with Vice President Dick Cheney in Cheney’s West Wing office at the White House. They knew each other “very well,” as Raymond put it later. Indeed, Raymond had known Cheney for more than two decades, dating back to the period when Cheney was a congressman from Wyoming. They had hunted quail and pheasants together. They were compatible personalities—both reticent, bred on the cold plains of the upper Midwest, and both educated at the University of Wisconsin. They were ardent in their free-market views, inclined to a certain tough bluntness, and not very much worried about what others thought about them, particularly bicoastal media elites and liberal intelligentsia.

During the 1990s, the Cheneys and the Raymonds had lived near one another in the old-line Preston Hollow and Highland Park neighborhoods of Dallas. Cheney served after 1995 as chief executive of Halliburton; his company contracted regularly to provide services to Exxon. (Halliburton did not seek to own and produce oil and gas directly, as ExxonMobil did, but made its money by providing construction and engineering services under contract to oil producers, whether they were government-owned companies or private corporations.) Socially, Raymond’s wife, Charlene, and Cheney’s wife, Lynne, saw each other not only in Dallas, but at retreats and meetings of the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, a free-market think tank where Raymond served on the board and Lynne served as a senior fellow. When Raymond sat down with Cheney after the latter’s swearing in as vice president, the meeting was best understood as a discussion between like-minded peers and friends who were comparing notes at the cusp of a new project.

“Look,” Raymond told Cheney, as he recalled it later, “my view is this country is going to be an importer [of oil] for as far as the eye can see. If you believe that to be the case, what things can we do?” Raymond answered his own question: “The first thing anybody will tell you is you have to have diversification of supply—you can’t get yourself in the position where you only have one supplier.”

That situation had developed between the United States and the Middle East. To overcome this bottleneck of geopolitical dependency, Raymond said, the United States had to be “engaged every place, every place you can go. . . . Even in the North Slope of Alaska.” Raymond felt that “one of the key issues in foreign policy” was how to manage the challenge of increasing access to new oil supplies. As he recalled it, he told Cheney, “We should be trying to encourage, as a matter of foreign policy, having countries develop their natural resources,” so that the United States could have “as diverse a portfolio of supplies as you can have, so that you don’t get yourself beholden to any one person.”

1

ExxonMobil had enjoyed easy access to high-ranking government officials during the Clinton administration; when the corporation’s Washington representatives needed a meeting, they almost always got one. Raymond told colleagues that ExxonMobil enjoyed access to the administration that was comparable to the halcyon years of the Reagan presidency. Clinton appointees approved the Exxon and Mobil merger with a minimum of fuss. Al Gore’s candidacy for the White House, however, had attracted considerable resistance from the oil industry, in part because of Gore’s record of environmental activism. Oil and gas companies had donated $34 million to political candidates during the 2000 cycle—more than three fourths of that funding had gone to Republicans.

2

George W. Bush’s father had made his fortune in the oil patch, and the new president had run a wildcatting firm earlier in his career, less successfully. There was little mystery about how the Bush administration would proceed on energy policy. A few days before his meeting with Raymond, Bush had assigned Cheney to head a cabinet task force to make rapid recommendations. The speed with which the panel planned to issue its findings—just a few months would pass from the panel’s formation to the issuance of a finished report—made the initiative recognizable to Washingtonians as one of those precooked packages where the authors know much of the outcome in advance. The purpose of such a task force is typically not to deliberate over difficult problems, but to create a process whereby Congress, industry, and the incoming cabinet all become invested in a set of recommendations formally endorsed by a new president. These can then be quickly translated into executive orders, new regulations, and proposed laws.

Cheney ordered the task force to work in secret, to protect the prerogatives of the White House, and by doing so he made the group’s work a lightning rod for criticism and conspiracy fears. It took years of litigation to discover through partial document releases what intuition might have suggested at the time: Cheney favored energy deregulation and an aggressive push to open up oil and gas production in the United States, and he identified himself with the priorities of Lee Raymond, among other industry executives.

James J. Rouse, a United States Army veteran educated in Mississippi who ran ExxonMobil’s Washington, D.C., office, attended one of the Cheney panel meetings next door to the White House and presented some of the corporation’s forecasts about future global energy demand. It was rising, he noted, and so more oil and gas production would be required. But ExxonMobil did not require access to a midlevel panel staffed by civil servants to make its points to the Bush White House. Lee Raymond flew to Washington about every other month and met privately with Cheney on some of his visits, perhaps two or three times a year. If he needed to make a request or share an observation more urgently, all he had to do was pick up the telephone.

Cheney had seen for himself at Halliburton how geopolitics, resource nationalism, and the emergence of large state-owned oil companies had pinched Western oil companies as they attempted to replace the equity reserves they pumped and sold each year. One purpose of the preconceived energy task force Cheney led was to prepare for legislation designed to open up Alaska’s Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling. Raymond supported Cheney’s plan and railed regularly in public against what he regarded as the self-defeating energy policies of the United States, which restricted access to oil and gas on free-market American territory while exacerbating the country’s dependency on imports from unstable and nationalistic regimes. Compared with other oil majors, however, ExxonMobil was no longer a dominant player inside the United States. Chevron had inherited some of the longest-lived of Standard Oil’s American oil properties, in California, and Chevron and British Petroleum had moved more boldly than Exxon into the Gulf of Mexico when leasing opened during the Clinton administration. Exxon had opportunities to exploit oil and natural gas in Alaska, but held back from some expensive deals because Raymond had learned after the

Valdez

that the political risks posed by Alaska’s frontier-minded political culture and populist governors were comparable to those in West Africa.

Buoyed by the trust embedded in their long-lived friendship, Raymond and Cheney typically talked less about domestic oil policy issues than about developments overseas in the world’s best-endowed regions. Raymond might report on conversations he had recently had with the president of Kazakhstan or the foreign minister of Saudi Arabia. He might relay to Cheney insights about the Saudi royal court or requests about some problem Saudi leaders were having with the Bush administration. Cheney might share similar notes from his own conversations with foreign leaders. In protocol, power, and habit of mind, Raymond and Cheney were each, in effect, deputy heads of state—when they traveled, they met with kings and presidents, and perhaps ministers or chiefs of national oil companies, but rarely anyone less powerful. When the friends gathered in Washington, their meetings were strictly business. If Raymond needed only ten minutes to make his request about a Kazakh trade issue, for example, and Cheney was quickly satisfied with the ExxonMobil chief’s arguments, Raymond would not waste the vice president’s time any further. In the White House, a one-hour meeting was a lengthy one, and Lee Raymond knew what it was like to have a daily schedule that was oversubscribed.

E

xxonMobil’s interests were global, not national. Once, at an industry meeting in Washington, an executive present asked Raymond whether Exxon might build more refineries inside the United States, to help protect the country against potential gasoline shortages.

“Why would I want to do that?” Raymond asked, as the executive recalled it.

“Because the United States needs it . . . for security,” the executive replied.

“I’m not a U.S. company and I don’t make decisions based on what’s good for the U.S.,” Raymond said.

ExxonMobil executives managed the interests of the corporation’s shareholders, employees, and worldwide affiliates that paid taxes in scores of countries. The corporation operated and licensed more gas stations overseas than it did in the United States. It was growing overseas faster than at home. Even so, it seemed stunning that a man in Raymond’s position at the helm of an iconic, century-old American oil company, a man who was a political conservative friendly with many ardently patriotic officeholders, could “be so bold, so brazen.” Raymond saw no contradiction; he did indeed regard himself as a very patriotic American and a political conservative, but he also was fully prepared to state publicly that he had fiduciary responsibilities. Raymond found it frustrating that so many people—particularly politicians in Washington—could not grasp or would not take the time to think through ExxonMobil’s multinational dimensions, and what the corporation’s global sprawl implied about its relationship with the United States government of the day.

3

After the merger, ExxonMobil moved its Washington, D.C., office from Pennsylvania Avenue to K Street, in the heart of the capital’s lobbying district. The office occupied one high floor of a new complex constructed from pink granite and concrete. A turret, topped by an American flag, distinguished the building from the LEGOLAND of downtown Washington. Landscape paintings lined the walls of ExxonMobil’s suite; antique Mobil oilcans and Esso signs decorated the shelves of its conference rooms. The furniture and dark cherry wood paneling created a formal and professional atmosphere, but the office eschewed the garish luxuries of the capital’s big law firms and the D.C. outposts of Wall Street investment banks.

By the time of the merger with Mobil, the office’s director, James Rouse, had been with the company for thirty-seven years. The résumés of the lobbyists he hired spoke of technical competence and stolidity. ExxonMobil’s strategy was not so much to dazzle or manipulate Washington as to manage and outlast it.

The Washington office functioned not only as a liaison to the White House and Congress, and to industry associations such as the American Petroleum Institute, but also as a kind of embassy, to deepen ExxonMobil’s influence and connections in the foreign countries where it did the most business. International issues managers developed contacts with ambassadors and commercial representatives of foreign embassies. As this international group in the K Street office expanded, Robert Haines, a West Point graduate and Vietnam veteran, handled Asian embassies; Sim Moats, a former State Department diplomat, handled Africa; and Oliver Zandona, a Mobil career manager, watched the Middle East. They also worked the American bureaucracy, particularly the State Department and the National Security Council, to influence and understand U.S. policy. They maintained some contacts at the Central Intelligence Agency and other federal intelligence departments as well. The C.I.A. ran a station in Houston, where oil industry executives who traveled globally occasionally stopped by for informal exchanges about leaders and events abroad, but in Washington the corporation’s lobbyists tried to keep their distance from Langley, site of the C.I.A.’s headquarters, for fear that host governments where the corporation produced oil might mistake ExxonMobil as some sort of wing of the spy agency.

ExxonMobil relied mainly on lifelong career employees for much of its Washington lobbying. Lee Raymond kept the number of full-time lobbying staff relatively modest, partly to avoid attracting unfavorable attention from journalists or opponents in the environmental lobbies. Where possible, the corporation lobbied as part of an industry coalition, principally through the American Petroleum Institute. Yet Raymond maintained a strong core of ExxonMobil staff to work Capitol Hill, the White House, and regulatory agencies. Many of the corporation’s employee-lobbyists rotated into Washington from other corporate disciplines, with little or no prior experience of government affairs. “I think we did it in-house so we could get it done right,” said Joseph A. Gillan, who worked on environmental issues in the office around the time of the Mobil merger. “Exxon’s culture was, ‘Let’s do it ourselves.’”

4

The corporation did retain Washington law firms and outside lobbying shops as consultants, although relatively few during the first Bush term. But these hired guns dispensed advice to ExxonMobil on contracts and were not typically relied upon to deliver access—some of the outside retainers were even forbidden from attending meetings with public officials. Some of the key outsiders on retainer—former oil-friendly senators such as Don Nickles of Oklahoma and J. Bennett Johnston of Louisiana—attended a weekly meeting at ExxonMobil’s office to exchange intelligence and analysis about legislation, electoral politics, and energy issues. The meetings sometimes had an air of jockeying and showboating as the lobbyists competed to show how much inside knowledge they possessed (and therefore how much value their retainer contracts generated for the oil corporation). The corporation spent heavily on its Washington operation, but the great majority of its costs involved salaries and benefits for career employees. In 2001, ExxonMobil spent $6 million on its lobbying operation, but only $300,000 on outsiders. The next year, it spent $8.3 million in total, but only another $300,000 on contractors.

5