Queen by Right (2 page)

Authors: Anne Easter Smith

Tags: #Fiction, #Historical, #Biographical, #Romance, #General

Anne Neville (Nan), countess of Stafford,

Cecily’s sister

Richard, earl of Warwick,

Salisbury’s oldest son

John, Lord Montagu,

Salisbury’s third son

George Neville, archbishop of York, chancellor of England,

Salisbury’s fourth son

Ralph Neville, 2nd earl of Westmorland,

grandson of Ralph’s first marriage

Woodville family

Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers,

chamberlain to the duke of Bedford

Jacquetta St. Pol (see

Lancaster

),

his wife

Anthony Woodville,

his oldest son

Elizabeth Woodville,

his oldest daughter

Miscellaneous

(asterisk indicates fictional character)

William de la Pole, duke of Suffolk,

councillor to Henry VI

Humphrey Stafford, duke of Buckingham,

Anne Neville’s husband and a king’s councillor

Anne of Caux,

the York family nursemaid

*Rowena Gower,

Cecily’s attendant

*Constance LeMaitre,

Cecily’s attendant and physician

Gresilde Boyvile,

Cecily’s attendant

*Beatrice Metcalf, Cecily’s

attendant and later Meg’s

*Piers Taggett,

Richard’s falconer

Sir William Oldhall, speaker of the House of Commons,

one of Richard of York’s councillors

Roger Ree,

one of Richard’s ushers of the chamber

Father Richard Lessey,

Richard’s chaplain

Sir Henry Heydon,

Cecily’s steward

John Tiptoft, earl of Worcester,

Henry VI’s treasurer

*Ann Herbert,

Meg’s attendant

Joan of Arc,

also known as Jeanne d’Arc, La Pucelle or The Maid

Pierre Cauchon, bishop of Beauvais,

chief judge at the trial of Joan of Arc

*Mathilda Draper,

midwife

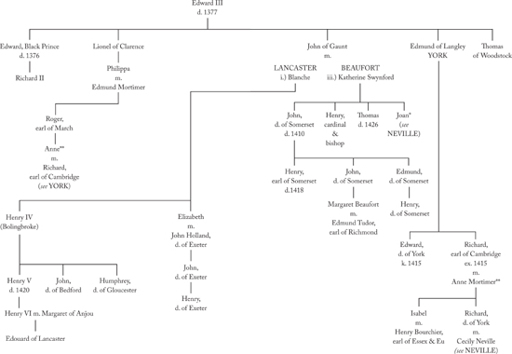

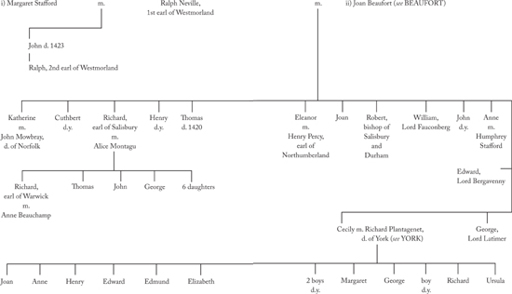

Plantagenet

Neville

Baynard’s Castle, London

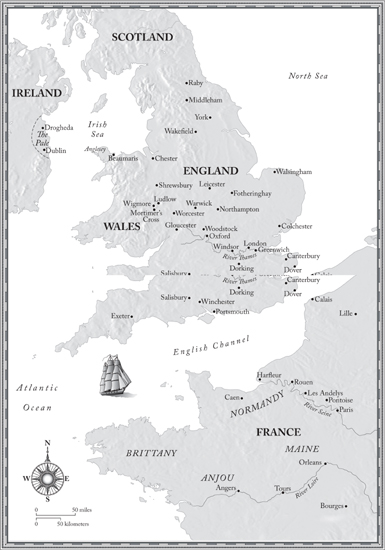

FEBRUARY 8, 1461

A

scream pierced Cecily’s dreamless sleep. She came awake in an instant as every mother might upon hearing her child in distress.

“Margaret,” she muttered into the gloom of her curtained comfort and then called to her attendant to light a taper. Her daughter’s sobbing made Cecily bark a little more impatiently: “Hurry, Gresilde, Lady Margaret is having another of her nightmares.” Hardly noticing the cold of the February night air, she pulled her velvet bedrobe around her, tucked her feet into matching slippers, and flung aside the heavy bed curtain. Dame Gresilde Boyvile held the taper aloft and lit her mistress’s way along the draughty corridor to Margaret’s chamber.

The servants shushing the distraught girl in the bed immediately fell to their knees in obeisance to the duchess of York as she swept in, her long sleeves trailing across the Turkey carpet.

“Margaret, my dearest child,” Cecily clucked, seating herself on the feather mattress and gathering her fourteen-year-old daughter into her arms. “’Twas but a dream. Calm yourself, I beg of you.” She thanked the ladies for their solicitation before drawing the curtains around her and Margaret.

“I dreamed of Micklegate again!” Margaret sobbed. “A terrible, ghastly dream. Why does it not go away?”

Margaret did not have to describe her nightmare. Her mother knew exactly what grisly scene the girl had conjured up.

Cecily’s husband, Richard, and her sweet son, Edmund, had met their death five weeks ago at Wakefield, not far from Sandal Castle, where they and the Yorkist army were keeping Christmas. They had not expected the king’s forces to come so soon nor to attack in the holy season, but it seems they were surprised, outnumbered, and Richard lost his life on the battlefield. Edmund, poor seventeen-year-old Edmund, Cecily grieved, was cut down in cold blood

while attempting to flee the field. Lord Clifford had found him hiding under a bridge and, crying vengeance for his own father’s death at St. Albans, had slit the lad’s throat while his soldiers held him down. Her gentle, second-oldest son—a tall, good-looking charmer like his elder brother Edward—was no more, and his head, together with those of Richard and her favorite brother, the earl of Salisbury, were set atop the city of York’s Micklegate on the orders of Queen Margaret. It was that hideous image that haunted young Meg night after night.

“Oh, why did they have to die?” Margaret sobbed.

Cecily tightened her hold on Margaret, inhaled the rosemary sweetness of the girl’s long, fair hair, and squeezed her eyes tightly shut. She had not wanted to believe the messenger’s tale of disaster. It had all happened so far away and, without physical proof, she could not grasp the reality of it. Her Richard beaten, killed, beheaded? Impossible. He had been part of her life since she was eight, and she could not imagine life without him.

“Oh, my dearest love . . .” she murmured.

She was unaware that she had spoken aloud until she felt Margaret gently pull away to study her. Cecily held herself erect, her face resuming the inscrutable expression she had learned to affect when in the public eye. But it was harder now after Wakefield.

“I am truly sorry, Mother,” Margaret whispered. “I was only thinking of my own anguish.” Her intelligent gray eyes searched her mother’s still lovely face for forgiveness and some uncharacteristic show of emotion.

Cecily was moved and tears threatened. Don’t cry, Cis, she told herself. This is not the time to cry. You must be strong for the children and strong for all the others who have given their service—and now their lives—to Richard’s cause.

“You thought I had a heart of stone? Nay! I must tell you that my loss is so great I feel my heart is shattered in shards that pierce my skin and make me want to scream in agony.” She pressed her hand to her heart and groaned. Then she raised her sad eyes to Margaret’s face and took the girl’s trembling chin between her fingers. “You know why your father and your brother died, my child. They died to right a wrong done to our house, and your father knew full well the price we all might have to pay. ’Tis the price all those born of royal blood are in danger of paying. You too must learn to sacrifice for your family whether it be the house of York or that of the man you wed. I will tell you now, Margaret, that as a woman born to a noble house, you may have your

share of happiness, but you will also know great heartache, for we are at the mercy of our menfolk. We must accept God’s will and bear it with dignity worthy of our name. Learn this now and well. You must learn how to bridle those feelings I see welling up in you every day. ’Tis what I have done these thirty years as duchess of York.” She bent and kissed Margaret’s face, smiling at her daughter’s astonishment. “Aye, Meg, I have as passionate a nature as you”—she tapped her breast—“but I have kept it to myself in here . . . except when I was with your father.” She chuckled. “I confess I was a handful when I was your age.”

Meg smiled, and Cecily pulled her into her arms again. “You will always have solace in prayer, my dear. Our Blessed Mary, saint of all women, is always there to listen.” The two women clung to each other for a few moments before they slid to their knees on the floor and made their supplications to the Virgin. Then Cecily tucked Meg into bed and padded wearily back to her own chamber.

Gresilde had thoughtfully placed a hot stone in the bed, and Cecily hugged its smooth warmth to her, curling herself into a ball and willing herself to sleep. Instead, the effort she had made for Margaret and the familiar position of childhood released all her pent-up despair, and her tears soon soaked her pillow. She put out her hand and felt the cold, empty place between the sheets where her husband should have been lying, and the ache in her heart became a violent pain. For a month she had maintained the demeanor of a noblewoman whose nickname—Proud Cis—had been well earned in the past few tumultuous years, but at that moment with her defenses finally breached, she allowed the flood of tears to spill unheeded and her thoughts to return to that golden autumn when Richard had come riding into her life.

She managed to smile then through her sniffling: Nay, she corrected herself, ’twas I who rode into his.

PART ONE

“A gracious lady!

What is her name, I thee pray tell me?”

“Dame Cecille, sir.”

“Whose daughter was she?”

“Of the Earl of Westmorland, I trowe the youngest,

And yet grace fortuned her to be the highest.”

FROM A FIFTEENTH-CENTURY BALLAD,

ANONYMOUS

1

Raby, Durham, 1423