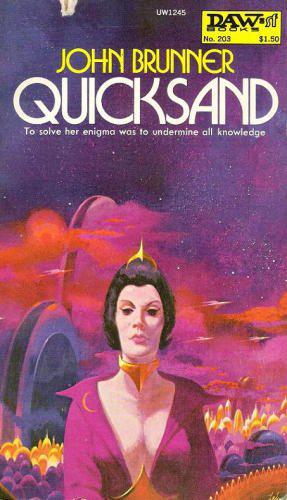

Quicksand

Authors: John Brunner

UW1245

DAW sf

No. 203 . . . $1.50

John Brunner

QUICKSAND

To solve her enigma was to undermine all knowledge

The girl walked naked

out of nowhere on a winter night

and to psychiatrist Paul Fidler it

was as if one of his own obsessive

visions of disaster took human form,

bringing nightmares to life.

Piquantly lovely, she belonged to no

known racial type. Of high intelli-

gence, she spoke a language no one

could be found to understand. Most re-

markable of all, commonplace objects

like clothing and cars were a mystery

to her.

Has she truly been cast adrift from

her own familiar world into another

branch of the universe?

Such was the frightening surmise

that gradually seemed to be the only

answer Paul could come up with. But

it implied things that he had never

dared to dream.

QUICKSAND

QUICKSAND

John Brunner

DAW BOOKS, INC.

Donald A. Wollheim, Publisher

-----------------------------

1301 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N. Y. 10019

Published by

THE NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY

OF CANADA LIMITED

Copyright ©, 1967 by Brunner Fact and Fiction Ltd.DAW sf

No. 203 . . . $1.50

John Brunner

QUICKSAND

To solve her enigma was to undermine all knowledge

The girl walked naked

out of nowhere on a winter night

and to psychiatrist Paul Fidler it

was as if one of his own obsessive

visions of disaster took human form,

bringing nightmares to life.

Piquantly lovely, she belonged to no

known racial type. Of high intelli-

gence, she spoke a language no one

could be found to understand. Most re-

markable of all, commonplace objects

like clothing and cars were a mystery

to her.

Has she truly been cast adrift from

her own familiar world into another

branch of the universe?

Such was the frightening surmise

that gradually seemed to be the only

answer Paul could come up with. But

it implied things that he had never

dared to dream.

QUICKSAND

QUICKSANDJohn Brunner

DAW BOOKS, INC.

Donald A. Wollheim, Publisher

-----------------------------

1301 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N. Y. 10019

Published by

THE NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY

OF CANADA LIMITED

Here, narrowing into now, the Past and Future

Are quicksand.

-- Randall Jarrell

The Knight, Death, and the Devil

was literally frightened.

doorjamb, and encountered books on a shelf. Startled, he had looked

instead of taking for granted and seen the big table in a new place,

the chairs in a new arrangement, everything moved to a different location.

a sort of outsize extended family; she had spent ten years here,

sometimes as a patient, sometimes as a member of the maintenance staff

doing cleaning work and washing-up, because she had nowhere else in

the world to go and nobody to care whether she lived or died. And once

or twice a year the signal would come that her lucid phase was ending:

one would walk into a room and find everything topsy-turvy, perhaps even

the carpet turned over. Meantime Mrs Gowler would have gone humming to

her next task, unaware of any departure from routine.

long-awaited new bookcases had been delivered and someone had spent

the afternoon filling them with medical journals previously kept on the

table in untidy stacks.

must have been a sight! Talk about reversion to infantile behaviour!

sometimes been haunted by the fear that he would waken one morning into

a world of strangers: parents who didn't recognise him as their son,

a school which didn't remember having him as a pupil. And once, much

later, it had all seemed to come true.

Glancing around to see if there was a substitute, be grimaced.

this year's budget. Anyhow: have to wait for a change of matron before

we get some good taste around this place.

Simultaneous to the tenth of a second, the clock in the tower overhead

ground towards striking, and he cringed. For most of the day he'd managed

to avoid noticing it, but last night, during his turn of duty . . .

clink

. Pause. Boom clink bang. Pause.

Clink

bang boom. And with a sense of relief from

unspeakable torture he heard it progress into the calm sequence of the

hourly chime: bong bong bong bong.

the clock-tower in '63. Probably wanted to silence the cracked bell.

the cook's helper, put her head around the door.

getting used to. Not so loud as the electric. Tea up in a couple of shakes!"

drew out and opened a magazine.

stuff fluphenazine enanthate. Relief for up to twenty-eight days from

a single injection. I should know about this; it sounds useful. Only . . .

Recollection of the letter in his pocket kept getting in the way.

balanced precariously beside the spoon. He accepted the tea, already

stewed sour although he'd got here a minute early. Stirring it listlessly

long past the point at which the sugar dissolved, he let his eyes roam

to the window.

had lain over the district, shedding halfhearted rain at intervals.

Now, with not long to go before sunset, a cold wind was brooming the

clouds eastward and wan sunlight was leaking through.

Lord, I must, stop this, or I'll be back to another of those childhood

obsessions: the endless questions about solipsism and how do you know

that what I see as red is the same as what you see as red?

if the red rock underneath the red soil were heaving itself up preparatory

to the titanic effort of building the mountains of Wales. A landscape

appropriate to castles, fit setting for heroic deeds and grand gestures.

Everything in view seemed to reinforce it. The parklike grounds had

once been a fine estate, and still were scrupulously tended, partly by

the patients as a valuable form of occupational therapy. But now rather

than a vast garden they constituted a sort of no-man's-land dividing the

hospital from the ordinary life of town and village beyond. Ignorant of

that, one might admire their stately beauty; informed, Paul associated

to wire entanglements and minefields.

grand to him. Now they seemed constricting, a planned wall excluding the

greater world. Some barely grey-green, some, in this month of February,

spined with naked trees, some forbiddingly dense with conifers, they

encircled town, hospital, Paul Fidler. Through this window, though not

from his own office, it was possible to see the point at which the single

main road breached the ring, but even there he was unable to imagine

open country, escape, freedom. For at this angle the two spool-shaped

cooling towers of the power station seemed to stand guard over the exit

from the valley, watch-posts of the forces prisoning him.

promised time.

Now it had sneaked past his defences. And . . .

am

glad.

For the latest of many times he glanced at the opening lines.

That fitted. One could hardly call a husband "Dear Paul" like a chance

acquaintance, and while the "darling" came readily enough in speech,

putting it starkly on paper would by now be so dishonest even Iris would

feel the incongruity.

Meg insist on my staying with them another few days and I can't turn

them down. I'm sure you won't mind too dreadfully. . . ."

his pocket.

is

a relief. Excuses? Why bother? I know exactly why I'm pleased.

Not for the reason I gave when she said she wanted to go and would I mind:

because I'm more free to study when I'm on my own. But because being with

Iris is a daylong and even a nightlong strain.

all the consequences which must inevitably flow from it was more than

he could contrive at the moment; as always happened to him when he was

confronted with a point of crisis in his life, possibilities multiplied

and multiplied in his imagination until they were beyond counting,

and some of them seemed almost physically real, they were so vivid.

He simply stood at the window and stared out, noting without paying

much attention that the wind from the west was now bringing up cloud of

its own to close the gap of lighter sky which had briefly relieved the

greyness of the February day.

about Mirza Bakshad, and both had just happened to him: the man's capacity

for moving without a whisper of sound, and his delight in excruciating

deformations of English.

elegantly. "The bookcases turned up, I see," he commented. "Not before

time, either. . . . Lil!

Li-il!

"

and biscuits.

the room.

Other books

Just Visiting by Laura Dower

The Baron's Bounty by Elizabeth Rose

The Wedding Wager by Regina Duke

Too Many Crooks Spoil the Broth by Tamar Myers

Soulwoven by Jeff Seymour

To Capture A Highlander's Heart: The Beginning by Teresa Reasor

Hooper, Kay - [Hagen 09] by It Takes A Thief (V1.0)[Htm]

The Case of the Weird Sisters by Charlotte ARMSTRONG, Internet Archive

Fragments by M. R. Field

Bitter Lemons of Cyprus: Life on a Mediterranean Island by Durrell, Lawrence