Quicksilver (68 page)

Authors: Neal Stephenson

Jack spent most of the ride home pondering what he’d seen. He noticed after a while that Enoch Root had been humming in a

satisfied way, evidently pleased with himself for having been able to so thoroughly shut Jack up.

“So Alchemy has its uses,” Enoch said, noting that Jack was coming out of his reverie.

“You invented this?”

“I improved it. In the old days they used only quicksilver and salt. The piles were cold, and they had to sit for a year. But when dross of copper is added, they become warm, and complete the change in three or four weeks.”

“The cost of quicksilver is—?”

Enoch chuckled. “You sound like your lady friend.”

“That’s the first question she’s going to ask.”

“It varies. A good price for a hundredweight would be eighty.”

“Eighty of

what

?”

“Pieces of eight,” Enoch said.

“It’s important to specify.”

“Christendom’s but a corner of the world, Jack,” Enoch said. “Outside of it, pieces of eight are the universal currency.”

“All right—with a hundredweight of quicksilver, you can make how much silver?”

“Depending on the quality of the ore, about a hundred Spanish marks—and in answer to your next question, a Spanish mark of silver, at the standard level of fineness, is worth eight pieces of eight and six Royals…”

“A

PIECE OF EIGHT HAS

eight

reals

—” Eliza said, later, having spent the last two hours sitting perfectly motionless while Jack paced, leaped, and cavorted about her bedchamber relating all of these events with only modest improvements.

“I know that—that’s why it’s called a piece of eight,” Jack said testily, standing barefoot on the sack of straw that was Eliza’s bed, where he had been demonstrating the way the workers mixed the amalgam with their feet.

“Eight pieces of eight plus six royals, makes seventy royals. A hundred marks of silver, then, is worth seven

thousand

royals…or…eight hundred seventy-five pieces of eight. And the price of the quicksilver needed is—again?”

“Eighty pieces of eight, or thereabouts, would be a

good

price.”

“So—those who’d make money need silver, and those who’d make silver need quicksilver—and a piece of eight’s worth of quicksilver, put to the right uses, produces enough silver to mint ten pieces of eight.”

“And you can re-use it, as they are careful to do,” Jack said. “You

have forgotten a few other necessaries, by the way—such as a silver mine. Mountains of coal and salt. Armies of workers.”

“All gettable,” Eliza said flatly. “Didn’t you understand what Enoch was telling you?”

“Don’t say it!—don’t tell me—just wait!” Jack said, and went over to the arrow-slit to peer up at the Doctor’s windmill, and down at his ox-carts parked along the edge of the stable-yard. Up and down being the only two possibilities when peering through an arrow-slit. “The Doctor provides quicksilver to the mines whose masters do what the Doctor wants.”

“So,” Eliza said, “the Doctor has—what?”

“Power,” Jack finally said after a few wrong guesses.

“Because he has—what?”

“Quicksilver.”

“So that’s the answer—we go to Amsterdam and buy quicksilver.”

“A splendid plan—if only we had money to buy it

with.

”

“Poh! We’ll just use someone else’s money,” Eliza said, flicking something off the backs of her fingernails.

N

OW, STARING DOWN THIS CROWDED

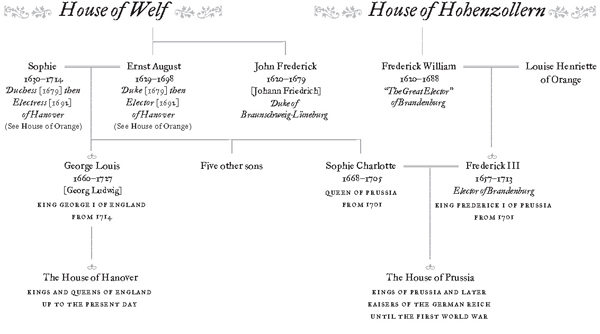

canal towards the city, Jack saw, in his mind, a map he’d viewed in Hanover. Sophie and Ernst August had inherited their library, not to mention librarian (i.e., the Doctor), when Ernst August’s Papist brother—evidently, something of a black sheep—had had the good grace to die young without heirs. This fellow must have been more interested in books than wenches, because his library had (according to the Doctor) been one of the largest in Germany at the time of his demise five years ago, and had only gotten bigger since then. There was no place to put it all, and so it only kept getting shifted from one stable to another. Ernst August apparently spent all of his time either fending off King Louis along the Rhine, or else popping down to Venice to pick up fresh mistresses, and never got round to constructing a permanent building for the collection.

In any event, Jack and Eliza had paused in Hanover for a few days on their journey west, and the Doctor had allowed them to sleep in one of the numerous out-buildings where parts of the library were stored. There had been many books, useless to Jack, but also quite a few extraordinary maps. He had made it his business to memorize these, or at least the parts that were finished. Remote islands and continents splayed on the parchment like stomped brains, the interiors blank, the coastlines trailing off into nowhere and simply ending in mid-ocean because no one had ever sailed farther than that, and the boasts and phant’sies of seafarers disagreed.

One of those maps had been of trade-routes: straight lines joining city to city. Jack could not read the labels. He could identify London and a few other cities by their positions, and Eliza helped him read the names of the others. But one city had no label, and its position along the Dutch coast was impossible to read: so many lines had converged on it that the city itself, and its whole vicinity, were a prickly ink-lake, a black sun. The next time they’d seen the Doctor, Jack had triumphantly pointed out to him that his map was defective. The arch-Librarian had merely shrugged.

“The Jews don’t even bother to give it a name,” the Doctor had said. “In their language they just call it

mokum

, which means ‘the place.’”

From desire, ariseth the thought of some means we have seen produce the like of that which we aim at; and from the thought of that, the thought of means to that mean; and so continually, till we come to some beginning within our own power.

—H

OBBES,

Leviathan

A

S THEY CAME CLOSER

to The Place, there were many peculiar things to look at: barges full of water (fresh drinking-water for the city), other barges laden with peat, large flat areas infested with salt-diggers. But Jack could only gawk at these things a certain number of hours of the day. The rest of the time he gawked at Eliza.

Eliza, up on Turk’s back, was staring at her left hand so fixedly that Jack feared she had found a patch of leprosy, or something, on it. But she was moving her lips, too. She held up her right hand to make Jack be still. Finally she held up the left. It was pink and perfect, but contorted into a strange habit, the long finger folded down, the thumb and pinky restraining each other so that only Index and Ring stood out.

“You look like a Priestess of some new sect, blessing or cursing me.”

“D” was all she said.

“Ah, yes, Dr. John Dee, the famed alchemist and mountebank? I was thinking that with some of Enoch’s parlor tricks, we could fleece a few bored merchants’ wives…”

“The letter D,” she said firmly. “Number four in the alphabet. Four is this,” holding up that versatile left again, with only the long finger folded down.

“Yes, I can see you’re holding up four fingers…”

“No—these digits are

binary.

The pinky tells ones, the ring

finger twos, the long finger fours, the index eights, the thumb sixteens. So when the long finger

only

is folded down, it means four, which means D.”

“But you had the thumb and pinky folded down also, just now…”

“The Doctor also taught me to encipher these by adding

another

number—seventeen in this case,” Eliza said, displaying her right with the thumb and pinky tip-to-tip. Putting her hand back as it had been, she announced, “Twenty-one, which means, in the English alphabet, U.”

“But what is the point?”

“The Doctor has taught me to hide messages in letters.”

“It’s your intention to be

writing letters

to this man?”

“If I do not,” she said innocently, “how can I expect to

receive

any?”

“Why would you

want

to?” Jack asked.

“To continue my education.”

“Owff!” blurted Jack, and he doubled over as if Turk had kicked him in the belly.

“A guessing-game?” Eliza said coolly. “It’s got to be either: you think I’m

already

too educated, or: you hoped it would be something else.”

“Both,” Jack said. “You’ve put

hours

into improving your mind—with

nothing

to show for it. I’d hoped you had gotten

financial backing

out of the Doctor, or that Sophie.”

Eliza laughed. “I’ve told you, over and over, that I never came within half a mile of Sophie. The Doctor let me climb a church-steeple that looks down over Herrenhausen, her great garden, so that I could watch while she went out for one of her walks. That’s as close as someone like me could ever come to someone like her.”

“Why bother, then?”

“It was enough for me simply to lay eyes on her: the daughter of the Winter Queen, and great-granddaughter of Mary Queen of Scots. You would never understand.”

“It’s just that you are always on about money, and I cannot see how staring at some bitch in a French dress, from a mile away, relates to that.”

“Hanover is a poor country anyway—it’s not as if they have much money to gamble on our endeavours.”

“Haw! If that’s poverty, give me some!”

“Why do you think the Doctor is going through such exertions to find investors for the silver mine?”

“Thank you—you’ve brought me back to my question: what does the Doctor want?”

“To translate all human knowledge into a new philosophical language, consisting of numbers. To write it down in a vast Encyclopedia that will be a sort of machine, not only for finding old knowledge but for making new, by carrying out certain logical operations on those numbers—and to employ all of this in a great project of bringing religious conflict to an end, and raising Vagabonds up out of squalor and liberating their potential energy—whatever

that

means.”

“Speaking for myself, I’d like a pot of beer and, later, to have my face trapped between your inner thighs.”

“It’s a big world—perhaps you and the Doctor can both realize your ambitions,” she said after giving the matter some thought. “I’m finding horseback-riding

enjoyable

but ultimately

frustrating.

”

“Don’t look to

me

for sympathy.”

The canal came together with others, and at some point they were on the river Amstel, which took them into the place, just short of its collision with the river Ij, where it had long ago been dammed up by the beaver-like Dutchmen. Then (as Jack the veteran reader of fortifications could see), as stealable objects, lootable churches, and rapable women had accumulated around this Amstel-Dam, those who had the most to lose had created Lines of Circumvallation. To the north, the broad Ij—more an arm of the sea than a proper river—served as a kind of moat. But on the landward side they’d thrown up walls, surrounding Amstel-Dam in a U, the prongs of the U touching the Ij to either side of where the Amstel joined it, and the bend at the bottom of the U crossing the Amstel upstream of the Dam. The dirt for the walls had to come from somewhere. Lacking hills, they’d taken it from excavations, which conveniently filled with ground-water to become moats. But to the avid Dutch there was no moat that could not be put to work as a canal. As the land inside each U had filled up with buildings, newly arrived strivers had put up buildings

outside

the walls, making it necessary to create new, larger Us encompassing the old. The city was like a tree, as long as it lived surrounding its core with new growth. Outer layers were big, the canals widely spaced, but in the middle of town they were only a stone’s throw apart, so that Jack and Eliza were always crossing over cleverly counter-weighted drawbridges. As they did so they stared up and down the canals, carpeted with low boats that could skim underneath the bridges, and (on the Amstel, and some larger canals) creaking sloops with collapsible masts. Even the small boats could carry enormous loads below the water-line. The canals and the boats explained, then, why it was possible to move about in Amsterdam at all: the torrent

of cargo that clogged roads in the countryside was here transferred to boats, and the streets, for the most part, opened to people.

Long rows of five-story houses fronted on canals. A few ancient timber structures still stood in the middle of town, but almost all of the buildings were brick, trimmed with white and painted over with tar. Jack marvelled like a yokel at the sight of barn doors on the fifth story of a building, opening out onto a sheer drop to a canal. A single timber projected into space above to serve as a cargo hoist. Unlike those Leipziger houses, with storage only in the attic, these were for nothing

but.

The richest of those warehouse-streets was Warmoesstraat, and when they’d crossed over it they were in a long plaza called Damplatz, which as far as Jack could tell was just the original Dam, paved over. It had men in turbans and outlandish furry hats, and satin-clad cavaliers sweeping their plumed chapeaus off to bow to each other, and mighty buildings, and other features that might have given Jack an afternoon’s gawking. But before he could even begin, some kind of phenomenon on the scale of a War, Fire, or Biblical Deluge demanded his attention off to the north. He turned his face into a clammy breeze and stared down the length of a short, fat canal to discover a low brown cloud obscuring the horizon. Perhaps it was the pall of smoke from a fire as big as the one that had destroyed London. No, it was a brushy forest, a leafless thicket several miles broad. Or perhaps a besieging army, a hundred times the size of the Turk’s, all armed with pikes as big as pine-trees and aflutter with ensigns and pennants.