Rags & Bones: New Twists on Timeless Tales (38 page)

Read Rags & Bones: New Twists on Timeless Tales Online

Authors: Melissa Marr and Tim Pratt

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction / Short Stories, Juvenile Fiction / Fantasy & Magic, Juvenile Fiction / Fairy Tales & Folklore - Adaptations, Juvenile Fiction / Fairy Tales & Folklore - Anthologies

Yes, I once knew joy.

“My daughter’s name is Aisha,” I say. My voice, her name, is sweet and

strong to my own ears. Like an angel’s war horn. This place had nearly made me forget that I can speak!

“My brothers were Abdullah and Abdul Hakam.”

Redcrosse’s eyes widen with shock and fury, and he bares his teeth.

Again I fix my eyes on my lost shield.

Ain. Ba. Dal.

The letters of my name weave themselves into words.

Lam. Waw.

I am

not

Joyless. I have

never

been Joyless. “You have lost,

creature. I am

Abdul Wadud

!” I shout at the Saint. “Abdul Wadud, the Servant of God the Loving!”

And as I raise my sword and go to my death, I am smiling.

A

UTHOR’S

N

OTE

…………………………………

Sir Edmund Spenser’s

The Faerie Queene

is, in many ways, the unacknowledged urtext of the modern Anglophone epic fantasy novel. Everything we love about epic fantasy—sword fights, monsters, jaw-dropping scale, a cast of thousands, deliberate antiquarianism, the ability to make magic real to the “rational” reader—is there in

The Faerie Queene

. Book One, at least,

is one of the masterpieces of English literature.

However,

The Faerie Queene

also prefigures many of epic fantasy’s weaknesses: It rambles horribly in later books (and was in fact never finished). There’s far too much description of clothing. More important, via a series of gruesome caricatures—of women, of Arabs, of Catholics—Spenser sets a sort of precedent for epic fantasy’s all-too-common

hatred of the Other. Despite this, or perhaps because of it, Book One’s recurring Muslim villains—the “Saracen” brothers Sansfoy, Sansloy, and Sansjoy—have always spoken to me. What was it like for

them

, being trapped in this hateful allegory? That question led to this story …

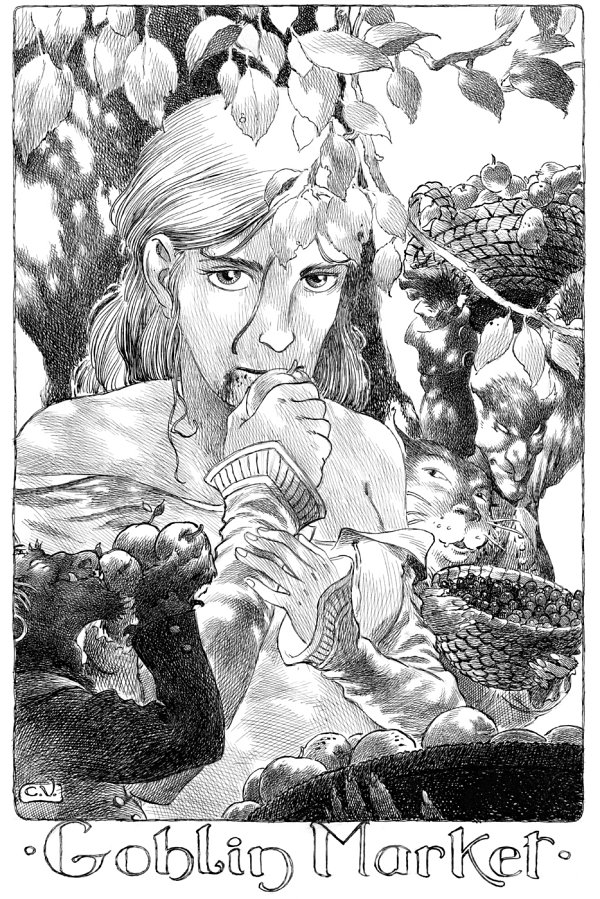

“Goblin Market”

(1862). The reclusive Christina Rossetti was already a very popular English poet before she published this long poem. Peopled as it is with two loyal sisters and a host of little goblin men offering their enticing wares, it was first thought to be merely a fairy tale intended for children. But the careful reader has only to ponder the “Hug me, kiss me, suck my juices, squeezed

from goblin fruit for you” or “Eat me, drink me, love me; For your sake I have braved the glen, and had to do with goblin men” to see other levels to her enticing poem. This subtle, erotic subtext has, over the years, enticed many illustrators to draw from it. Christina’s brother, Dante Gabriel Rossetti (the Pre-Raphaelite painter), was the first, followed by Laurence Housman and Arthur Rackham among

many, many others.

—Charles Vess.

G

ENE

W

OLFE

I ought never to have read the letter. More signally, I ought never to have returned to the Ivory Coast. The letter found me at Cape Town. It was accompanied by another, from one Dubois. His went something like this:

For the present, monsieur, I have the honor to hold the position of your good friend M. Bercole, who is, alas, somewhat ill. This is to say, I am acting administrator

general of this district. It is to be hoped that my term of office will be but short. The letter I enclose reached my hands only yesterday, though it has been weeks, it may be months, in the hands of others. Rest assured, monsieur, that it has been read not by M. Bercole nor by myself, and that those who placed it in our hands had not the capacity.

I have saved the letter itself. I will transcribe

it here.

My Dear Friend:

Do not be offended, I beg you, by this salutation. When one drowns, any passerby is the dearest of friends.

You may recall that the administrator general advised Joseph to shoot me. For me to appeal to him now would be hopeless. Your eyes were filled with a pity which I then resented. Yes, I was such a fool! Joseph is dead. He was killed by a leopard, the workers say.

There is no work for them and no chance of payment should they work. They are fewer each day. I am imprisoned in this cage. Sometimes I am fed. More often I am not. Please help me! You look so kind! Please help! Marthe Hecht

I went. What else could I do? A trading schooner returned me to the Ivory Coast, a voyage of thirty-two days that might easily have taken much longer. Bercole was clearly

too ill to accompany me, though he wished to go. Dubois, the new man, flatly refused. To give him his due, he had nearly worried himself into a breakdown, crushed under the new responsibilities fate had heaped upon him; the trek up-country would have done him good. I tried to persuade him, but he was adamant. Seeing that argument was useless, I left as soon as possible, with four porters and a native

gendarme called Jakada. He had brought the letter and so was a potential source of information about the Hecht plantation and specifically about the condition of the late owner’s wife. I write “potential” because I really got few facts from him. She was

kai gaibou,

a leopard, meaning possessed by a panther spirit. When I inquired concerning her cage, he affirmed that she was locked inside it—but

soon spoke of her roaming at night in search of prey. When I reminded him that he had told me she was caged, he shrugged.

I have written earlier of the baboons. They were as numerous

as ever and seemed even more curious about us than before. They were, I believe, simply bolder in their curiosity because my party was smaller than Bercole’s had been. Here I ought not, perhaps, record an experience

that I still find uncanny and has no connection that I can see to what was to follow. Between one step and the next I found myself seeing myself and our party through the eyes of a baboon. It (or perhaps

she

) was normal, as were the rest of the troop, her friends and relations. I was utterly askew, a pale cripple forced to walk on my hind legs alone and covered with scabs. This took, as I have

tried to say, no time at all. Then it was over, leaving me with the feeling that something intended for a baboon had been delivered to me by mistake. Before I had taken another ten strides, a young female ran up to me, felt the material of my shorts, and took my hand. For the next quarter hour or so we walked on in that manner, the young female reaching up to clasp my hand and walking easily on three

legs. At length she released me and bounded away. I have no explanations to offer. Not even for a moment did I suppose that before a week had passed I would be shooting these same baboons.

Reaching the Cavally, we forded it and marched upriver for three long days, fording it again when we came in sight of the plantation that had been Hecht’s. It appeared deserted, its fields returning to jungle.

Seeing it, I felt quite sure his wife was dead.

We had come too far, however, to return to the coast without investigating, and it seemed at least possible that a few items of interest might be found in the bungalow. I told Jakada and the porters we would camp here for the night, and perhaps for two nights. When we had set up our camp, Jakada and I entered the bungalow.

We had no more than set

foot in it when a woman’s voice called, “Oku? Amoue?” Tired and sweating as I was, I ran toward it.

The cage was built against the side of the bungalow. A door of the kitchen gave easy access to it, and to the wide slot in its barred door through which trays were passed. I saw her then, her hands gripping the bars, and saw, too, the unmistakable joy she felt at the sight of me. It touched my

heart, and touches it still. Yes, even after all that has happened.

I would have released her at once if I could, but the cage door was closed with a formidable padlock, and the key was nowhere in sight. When I asked Marthe whether she knew where it was kept, she replied, “Please do not call me by that name. It is not mine. Joseph used it because he wished the world to think me French. Though

I loved him, I never loved the name he gave me.”

I was tempted to question her then, but the chief business of the hour, as I then saw it, was to free her. Thus I asked again where I might find the key.

“Joseph always returned it to his pocket,” she said. “He used to visit me in the evening. I feel quite certain you understand.”

Of course I said I did, and went off looking for the key.

After

an hour or so it occurred to me that if I had been in Hecht’s position I would certainly have kept the key in my pocket, and not in a drawer of my desk or any other such place. Some of his employees might well have been minded to assault his wife or even to kill her. They might perhaps have accomplished her death by thrusting spears between the bars of the cage, but it would have been difficult

and perhaps impossible. If they could enter her cage, however, one slash of a cane knife might easily have been enough. Those who had found Hecht’s

body might well have taken the key, but where were they now? Except for Hecht’s widow, who could not leave, the plantation seemed utterly deserted.

And if they had not taken the key, it had presumably been interred with Hecht. The prospect of exhuming

a corpse, one that had spent months in a shallow grave in central Africa, positively horrified me.

By that time I had discovered a workshop in one of the outbuildings. Such tools as remained there were few and simple, but I collected them and attacked the bars with a will.

Two hours of hard work availed nothing. My porters and I prepared a tray for the imprisoned woman. Her disappointment as

she accepted it was as obvious as it was understandable.

I had washed and taken refuge beneath my mosquito net, sick with self-recrimination. I ought to have brought tools—no doubt they could have been purchased without difficulty in Abidjan. I ought to have brought skeleton keys, and asked a locksmith’s advice, too. I ought to have learned the location of Hecht’s grave. Though his widow could

never have seen it, she might have known it. I could have sent Jakada and a couple of porters to look for it. Before I fell asleep, I decided that since all my labor on the bars had been fruitless, I would concentrate my efforts on the lock and the hinges in the morning.

And that is what I did. In a little over an hour I had drawn the pins of all three hinges and opened the door. But I have omitted

too much by speaking of that humble triumph now. Not long after I had fallen asleep, I was awakened by a pistol shot. I called out, and one of the porters came. He told me that Jakada had shot at a leopard. He himself had not seen this leopard; Jakada had seen it and shot at it. I told him to send Jakada to me;

but if Jakada came it was only after I had returned to blissful sleep, and Jakada did

not wake me.

That night I dreamed that a woman’s naked body was stretched upon my own, and that she was kissing me. It was, I know, a dream of a kind only too common in men who have been long separated from the warm commerce of the sexes. Later this woman lay close beside me whispering, promising all the delights of marriage with none of its pains. I longed to tell her its pains would be my delight,

if only we were wed; but I could not speak, only listen to her; and her voice might have been that of a breeze from the sea.

There has been another loss, a small boy this time. Sailors and volunteers are searching the ship. If we were ashore, I might buy handcuffs at some shop catering to the police. Then I could handcuff Kay to me and entrust the key to a friend. Nothing of the sort seems possible

here. I would have the steward lock us in if that might be done; but the mechanism of our stateroom door prevents it, locking automatically when we go out but opening readily to those within.

How then, does Kay reenter? She must possess a key of her own. If I can find it and drop it over the side, she will be unable—no, what a fool I am! She takes my key from my pocket while I sleep. Thus the

solution is simple. I must hide the key. She will not dare to leave unless she can reenter. I will hide it tonight, but I will most certainly not name its hiding place here.

Later. There, it is done! Kay has not returned; presumably she is still playing cards in the lounge. I will go out and rejoin her. When we return to this stateroom, I will tell her that I have left my key behind (which will

in fact be sober truth) and get the steward to unlock the door and let us in. Clearly I cannot do the

same thing tomorrow night, but I will have all day in which to think of a new plan. Or something better, I hope.

Morning. Kay was still sleeping when I left. My little ruse seems to have worked perfectly. The key was where I had hidden it, and I saw nothing to indicate that Kay had gone out.

What I must do tonight, clearly, is return to our stateroom before her and conceal the key. When she returns, she will find me bathed and in my robe. In the morning I must rise before her and retrieve the key before she wakes.

But what am I to do when we reach New York?

Kay excused herself at dinner, I assumed to go to the ladies’ room. She did not return. When she had been gone for half an

hour, I enlisted the colonel’s wife. She returned to say that Kay was not in there. She had looked in the booths, had looked everywhere, and there was no sign of her. Mrs. Van Cleef suggested that she might have been taken ill. It seemed unlikely—the South Atlantic was anything but rough—but I nodded, left, and toured the railing. She was not there.