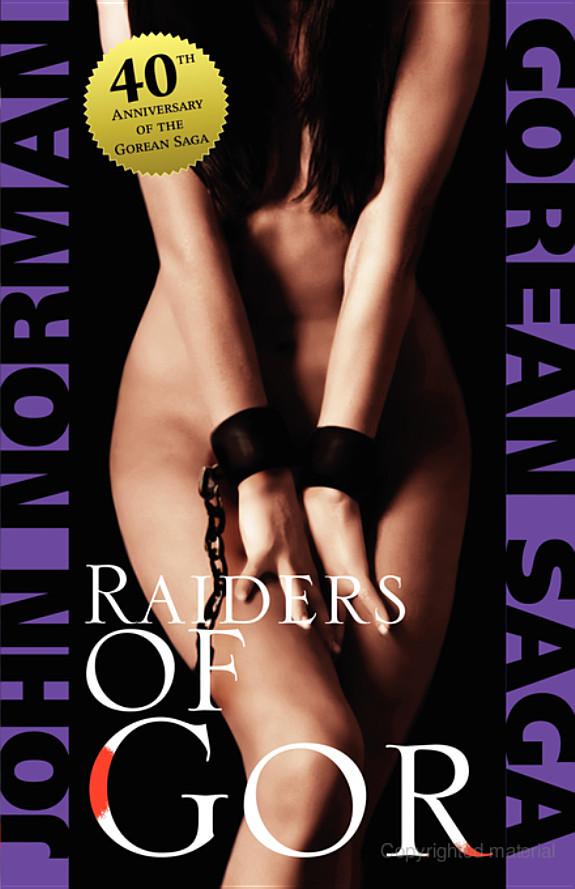

Raiders of Gor

Authors: John Norman

Tags: #Science Fiction, #Fiction, #General, #Fantasy, #Adventure, #Historical, #Erotica, #Thrillers, #Gor (Imaginary Place), #Cabot; Tarl (Fictitious Character)

06 Raiders of GorRaiders or Gor

John Norman

Chronicles of Counter-Earth Volume 6

1

The Blood Mark

I could smell the sea, gleaming Thassa, in the myths said to be without a

farther shore.

I reached down from the rush craft and took a palm of water into my hand and

touched my tongue to it. Thassa could not be far beyond.

I took the triangular-bladed tem-wood paddle and moved the small craft, light

and narrow, large enough scarcely for one man, ahead. I was formed of pliant,

tubular, lengthy Vosk rushes, bound with march vine.

To my right, some two or three feet under the water, I saw the sudden, rolling

yellowish flash of the slatted belly of a water tharlarion, turning as it made

its swift strike, probably a Vosk carp or marsh turtle. Immediately following I

saw the water seem to glitter for a moment, a rain of yellowish streaks beneath

the surface, in the wake of water tharlarion, doubtless its swarm of scavengers,

tiny water tharlarion, about six inches long, little more than teeth and tail.

A brightly plumaged bird sprang from the rushes to my left, screaming and

beating its sudden way into the blue sky. In a moment it had darted again

downward to be lost in the rushes, the waving spore stalks, the seed pods of

various growths of the Gorean tidal marshes. Only one creature in the marshes

dares to outline itself against the sky, the predatory UI, the winged

tharlarion.

It was difficult to see more than a few feet ahead: sometimes I could see no

further than the lifted prow of my small craft, as it nosed its way among the

ruses and the frequent rence plants.

It was the fourth day of the sixth passage hand, shortly before the Autumnal

Equinox, which in the common Gorean calendar begins the moth of Se’Kara. In the

calendar of Ko-ro-ba, which, like most Gorean cities, marks years by its

Administration of my father, Matthew Cabot. In the calendar of Ar, for those it

might interest, it was the first year of the restoration of Marlenus, Ubar of

Ubars, but, more usefully for the purposes of consolidating the normal chaos of

Gorean chronology, it was the year 10,119 Contasta Ar, that is, from the

founding of Ar.

My weapons shared the boat, with a gourd of water and a tin of bread and dried

bosk meat. I had the Gorean short sword in its scabbard, my shield and helmet,

and, wrapped in leather, a Gorean long bow of supple Ka-la-na wood, from the

yellow wine trees of Gor, tipped with notched bosk horn at each end, loose

strung with help and whipped with silk, and a roll of sheaf and flight arrows.

The bow is not commonly favored by Gorean warriors, but all must respect it. It

is the height of a tall; its back, away from the bowman, is flat; its belly,

facing the bowman, is half-rounded; it is something lika an inch and a half wide

and an inch and a quarter thick in the center; it has considerable force and

requires considerable strength to draw; many men, incidentally, even some

warriors, cannot draw the bowy; nine of the arrrows can be fired aloft before

the first falls again to the earth; at point-blank range it can be fired

completely through a four-inch beam; at two hundered yards it can pin a man to a

wall; at four hundred yards it can kill the huge, shambling bosk; its rate of

fire is nineteen arrows in a Gorean Ehn, about eighty Earth seconds; and a

skilled bowman, but not an extradordinary one, is expected to be able to place

these nineteen arrows in on Ehn into a target, the size of a man, each a hit, at

a range of some two hundred and fifty yards. Yet, as a weapon, it has serious

disadvantages, and on Gor the crossbow, inferior in accuracy, range and rate of

fire, with its heavy cable and its leaves of steel, tends to be generally

favored. The long bow cannot well be used except in a standing, or at least

kneeling, position, thus making more of a target of the archer; the long bow is

difficult to use from a saddle; it is impractical in close quarters, as in

defensive warfare of in fighting from room to room; and it cannot be kept set,

loaded like a firearm, as can the crossbow; the crossbow is the assassin’s

weapon, par excellence; further, it might be mentioned that, although it takes

longer to set the crossbow, a weaker man, with, say, his belt claw or his

winding gear, can certainly manage to do so; accordingly, for every man capable

of drawing a warrior’s long bow there will be an indefinite number who can use

the crossbow; lastly, at shorter distances, the crossbow requires much less

skill for accuracy than the long bow.

I smiled to myself.

It is not difficult to see why, popularly, the crossbow should be regarded as a

generally more efficient weapon that the long bow, in spite of being inferior to

it, in the hands of an expert, in range, accuracy and rate of fire. Well used,

the long bow is a far more devastating weapon than its rival, the crossbow; but

few men had the strenght and eye to use it well; I prided myself on my skill

with the weapon.

I paddled along, gently, kneeling on the rushes of my small, narrow craft.

It is the weapon of a peasant, I heard echoing in my mind, and again smiled. The

Older Tarl, my former master-at-arms, had so spoken to me years before in

Ko-ro-ba, my city, the Towers of the Morning. I looked down at the long, heavy,

leather-wrapped bow of supple Ka-la-na wood in the bottom of the rush craft.

I laughed.

It was true that the long bow is a weapon of peasants, who make and use them,

sometimes with great efficiency. That face, in inself, that the long is a

peasant weapon, would make many Goreans, particularly those ont familiar with

the bow, look down upon it. Gorean warriors, generally drawn from the cities,

are warriors by blood, by caste; moreover, they are High Caste; the peasants,

isolate in their narrow fields and villages, are Low Caste; indeed, the Peasant

is regarded, by those of the cities, as being little more than an ignoble brute,

ingnorant and superstitious, venal and vicious, a grubber in the dirt, a

plodding animal, an ill-tempered beast, something at best cunning and

treacherous; and yet I knew that in each dirt-floored cone of straw that served

as the dwelling place of a peasant and his family, there was, by the fire hole,

a Home Stone; the peasants themselves, though regarded as the lowest caste on

all Gor by most Goreans, call themselves proudly the ox on which the Home Stone

rests, and I think their saying is true.

Peasants, incidentally, are seldom, except in emergencies, utilized in the armed

forces of a city; this is a futher reason why their weapon, the long bow, is

less known in the cities, and among warriors, than it deserves to be.

The Gorean, to my mind, is often, though not always, bound by historical

accidents and cultrual traditions, which are then often rationalized into a

semblance of plausibility. For example, I had even heard arguments ot the effect

that pleasants used the long bow only because they lacked the manufacturing

capablity to produce crossbows, as though they could not have traded their goods

or sold animals ot obtain crossbows, if they wished. Further, the heavy,

bronze-headed spear and the short, double-edged steel sword are traditionally

regarded as the worthy, and prime, weapons of the Gorean fighting man, he at

least who is a true fighting man; and similarly traditionally, archers, who slay

from a distance, not coming to grips with their enemy, with their almost

invisible, swiftly moving shafts of wook, those mere splinters, are regarded as

being rather contemptible, almost on the periphery of warriorhood; villains in

Gorean epics, incidentally, when not of small and despised castes, are likely to

be archers; I had heard warriors say that they would rather be poisoned by a

woman than slain by an arrow.

I myself, perhaps because I had been raised not on Gor, but on Earth, did not,

fortunately in my opinion, suffer from these inhibiting prepossessions; I could

use the long bow with, so to speak, no tincture of shame, no confusion of

conscience, without the least injury to my self-esteem; I knew the long bow to

be a magnificent weapon; accordingly, I made it my own.

I heard a bird some forth or fifty yards to my right; it sounded like a marsh

gant, a small, horned, web-footed aquatic fowl, brad-billed and broad-winged.

Marsh girls, the daughters of rence growers, sometimes hunt them with throwing

sticks.

In some cities, Port Kar, for example, the long bow is almost unknown. Similarly

it is not widely known even in Glorious Ar, the largest city of known Gor. It is

reasonably well know in Thentis, in the Mountains of Thentis, famed for her tarn

flocks, and in Ko-ro-ba, my city, the Towers of Morning. Cities vary. But

generally the bow is little known. Small straight bows, of course, not the

powerful long bow, are, on the other hand, reasonably common on Gor, and these

are often used for hunting light game, such as the brush-maned, three-toed

Qualae, the yellow-pelted, sing-horned Tabuk, and runaway slaves.

I heard another bird, another marsh gant it seemed, some fifty yards away, but

this time to my left.

I was late in the afternoon, the fourteenth Gorean Ahn I would have guessed.

Some swarms of insects hung in the sedge here and there but I had not been much

bothered: it was late in the year, and most of the Gorean insects likely to make

life miserable for men bred in, and frequented, areas in which bodies of

unmoving, fresh wather were plentiful. I did see a large, harmless zarlit fly,

purple, about two feet long with four translucent wings, spanning about a yard,

humming over the surface of the water then alighting and, on it’s padlike feet,

daintily picking its way across the surface. I flicked a salt leach from the

side of my light craft with the corner of the tem-wood paddle.

On river barges, for hundreds of pasangs, I had made my way down the Vosk, but

where the mighty Vosk began to break apart and spread into its hundreds of

shallow, constantly shifting channels, becoming lost in the vast tidal marshes

of its delta, moving toward gleaming Thassa, the Sea, I had abandoned the

barges, purchasing from rence growers on the eastern periphery of the delta

supplies and the small rush craft which I now propelled through the rushes and

sedge, the wild rence plants.

I noticed that one of these rence plants had, tied about it, below the tuft of

stamens and narrow petals, a white cloth, re-cloth.

I paddled over to look at the cloth. I looed about myself, and was for some time

quiet, not moving. Then I moved past the plant, parting the rence and passing

throug.

I heard again the cry of the marsh gant, from somewhere behind me.

No one had been found who would guide me into the delta of the Vosk. The

bargemen of the Vosk will not take their wide, broad-bottomed craft into the

delta. The channels of the Vosk, to be sure, shift from season to season, and

the delta is often little more than a trackless marsh, literally hundreds of

square pasangs of estuarial wilderness. In many places it is too shallow to

float even the great flat-bottomed barges and, more inmportantly, a path for

them would have to be cut and chopped, foot by foot, through the thickets of

rush and sedge, and the tangles of marsh vine. The most important reason for not

finding a guide, of course, even among the eastern rence growers, is that the

delta is claimed by Port Kar, which lies within it, some hundred pasangs from

its northwestern edge, bordering on the shallow Tamber Gulf, beyond wich is

gleaming Thassa, the Sea.

Port Kar, crowded, squalid, malignant, is sometimes referred to as the Tarn of

the Sea. Her name is a synonym in Gorean for cruelty and piracy. The fleets of

tarn ships of Port Kar are the scourge of Thassa, beautiful, lateen-rigged

galleys that ply the trade of plunder and enslavement from the Ta-Thassa

Mountains of the southern hemisphere of Gor to the ice lakes of the North; and

westward even beyond the terraced island of Cos and the rocky Tyros, with its

labyrinths of vart caves.

I knew one in Port Kar, by name Samos, a slaver, said to be an agent of

Priest-Kings.

I was in the delta of the Vosk, and making my way to the city of Port Kar, which

alone of Gorean cities commonly welcomes strangers, though few but exiles,

murderers, outlaws, thieves and cutthroats would care ot find their way to her

canaled darknesses.

I recalled Samos, slumped in his marble chair at the Curulean in Ar, seemingly

indolent, but indolent as might be the satisfied beast of prey. About his left

shoulder, in the manner of his city, he had worn the knotted ropes of Port Kar;

his garment had been simple, dark and closely woven; the hood had been thrown

back, revealing his broad, wide head, the close-cropped white hair; the face had

been red from windburn and salt; it had been wrinkled and lined, cracked like

leather; in his ears there wha been two small golden rings; in him I had sensed

power, experience, intelligence, cruelty; I had felt in him the presence of the

carnivore, at that moment not inclined to hunt or kill. I did not look forward