Rampage (23 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

Outside the Quonset, Constable Stephen Vigor heard the sounds of gunfire and screaming, and told his partner to radio for help. Vigor, with pistol drawn, made his way to the doorway of the hut, which was obscured by a jumble of police cars. Without warning, Roszko casually walked out of the Quonset, gripping an assault rifle. A .300 Magnum rifle was slung over his shoulder and a semi-automatic pistol tucked in his waistband. Spotting Vigor, a look of surprise came over Roszko’s face, and he fired twice. Both bullets missed their mark, the first pinging off a nearby police cruiser and the second shattering its mirror. Constable Vigor returned fire, striking Roszko in the thigh and hand. Dripping blood, Roszko staggered back inside the Quonset. Constable Hoogestraat pulled his vehicle in front of Vigor to shield him from further bullets. Hoogestraat took up position next to his partner, and both men nervously awaited round two of the shootout. From where they were standing, neither one could see inside the hut. They called out to Roszko and the other officers, but received no reply. The tension hung like frost in the cold Alberta air.

Over the next few hours, backup and emergency response teams arrived at the scene. Nobody would risk entering the Quonset lest Roszko have any tricks up his sleeve. It wasn’t until 2:00 p.m., when a Remote Mechanical Investigator (a robot with a camera attached) was sent in, that they learned of the horror that had unfolded. James Roszko lay dead among the corpses of all four constables. Wounded and outgunned, the outlaw had chosen to end his life by firing a pistol into his heart. A cop hater to the end, he hadn’t wanted to give them the satisfaction of finishing the job.

As Canada mourned the loss of four dutiful young RCMP officers, questions regarding the Mayerthorpe Tragedy inevitably emerged. Had the police taken the proper precautions? Could anything be done in future to prevent a similar incident from occurring? And underpinning both questions, who was James Michael Roszko?

Wicked Devil

When pressed by reporters to comment on his son Jim, eighty-year-old William Roszko replied that he hadn’t exchanged words with the “wicked devil” in almost a decade. Other Mayerthorpe-area residents referred to Jimmy Roszko as a walking time bomb. Unlike

Valery Fabrikant

and

Robert Cook

, who were liked or respected by some people, it seems there wasn’t an honest soul who could attest to a single virtue in Roszko’s character. Though his final body count numbered nowhere near that of

Alexander Keith Jr.

or

Marc Lépine

, he may be the most morally reprehensible Canadian rampage murderer in this book.

The second youngest of the Roszko children, Jim grew up in the Alberta countryside, 130 kilometres northwest of Edmonton. Both his father and brother have claimed he went astray in his early teens, when he began using drugs. This early experimentation should be viewed as symptomatic rather than causal. When an autopsy was conducted on Roszko following the Mayerthorpe tragedy, the medical examiner found no traces of any drugs or alcohol in his body whatsoever. Drugs hadn’t made him a monster: embryo psychopathy, an over-indulging mother, and a fanatically religious father had.

Like many who have made the Canadian prairies their home, William Roszko and Stephanie Liwczak were of Ukrainian stock. The two had met when William was a twenty-five-year-old farmer and Stephanie the seventeen-year-old daughter of a Catholic deacon. In November 1950 they married and settled down to work the land. Their first child, Billy, followed soon after in 1951. During an argument, Stephanie said that she was going to leave William, and attempted to wrest Billy from his hands. William responded by punching her in the mouth, chipping her tooth. “After that she never forgave me,” he moaned fifty-five years later. “She’s so stone-hearted.” William Roszko claimed that he never laid a hand on her again, and as a result she got “spoiled” and did “whatever she felt like.” Though William’s act was obviously barbaric, his son George corroborated that Stephanie never missed an opportunity to bring it up whenever they argued. Yet, despite their dysfunctional marriage, the Roszkos continued to have babies annually from 1953: Josephine, Pauline, George, John, Joseph, and on November 8, 1958, James.

Within months of Jimmy’s birth, William began to express irrational beliefs that the end of the world was drawing near. By 1960, he was plagued by dreams of Armageddon and final judgment, becoming convinced that God was using his dreams as a conduit to send him visions. In his diaries he wrote: “A very dark cloud began to come from the West, a terrible storm, and with g

reat noise like rushing waters, with thunder and roaring that I have never seen nor heard of in my life. And I heard the sounds of Angels’ trumpets. I thought it cannot be anything else but the end of the world.” Much to his wife’s embarrassment, William grew his beard to biblical proportions and began preaching of a 1961 apocalypse. His constant religious diatribes alienated their closest friends, many refusing to come over lest they be subject to one of his sermons. Even around his buddies at the bar, William would speak only of doom and prophecy. Whereas others could escape his constant proselytizing, his wife and children were forced to listen as he read scripture aloud for hours. By January 1960, Stephanie had reached her breaking point: she attempted suicide and had to have her stomach pumped at Mayerthorpe hospital. William finally tired of his apocalyptic obsession in 1961 (presumably because it didn’t come true), though his wife remained wracked with depression and anxiety. The couple had their seventh and final child together, Mary Ann, that same year.

Jimmy Roszko was a particularly adorable infant, coddled by almost everyone around him. Whether he was bouncing gleefully on a relative’s knee or being ferried around the countryside by his siblings in an old washtub, he must have felt like the centre of the universe. If Jimmy wanted something, he would throw an ungodly squealing tantrum until he got it. Instead of teaching him restraint, Stephanie would project the blame onto others: “You showed him that! You give it to him!” Also, unlike the other Roszko children, Jimmy never did chores, and inevitably, their lovable little brother transformed into a spoiled brat to be avoided at all costs. Jimmy was even spared the harsh discipline of his father’s strap.

“He’d somehow get away with his ways,” William later recounted. “One time, he hit one of the boys and I couldn’t catch up to him. He was such a sneaky, zigzagging person.”

As Jimmy’s elder brother John would later say in a CBC interview: “Those preschool years, that’s when the framework is b

uilt for the rest of your life. If you grow up out of your diapers thinking that everything is your way, and everything you feel is right, well, what do you think is going to happen?”

Stephanie continued to give Jimmy preferential treatment well into adulthood, even when it risked the safety of her other children. Doug, her younger son by another man, once testified under oath that Jimmy “was always kicking the shit out of me in the yard. We would be working on something and he would get mad, throw wrenches around, grab me, kaboof in the head. Mom never said anything.” On one occasion he showed Stephanie a crack in the bedroom wall where Jimmy had thrown him, and she allegedly replied, “What crack? I can’t see no crack?” When, in 1994, a grown man charged Jimmy with repeatedly sexually abusing him in the late 1980s, Stephanie openly challenged the victim’s story: “If it really happened, why didn’t you say something then?” Privately she admitted to another son that she knew Jimmy was guilty and had “problems.”

In the company of others, Jimmy learned to mask his self-centred nature, presenting himself as the perfect little boy. The Roszkos had a good reputation at school for being polite, well-behaved children — an “ideal family” who did everything together. Though not unintelligent, Jimmy lacked focus and achieved average grades. His parents’ turbulent marriage was likely the source of much distraction. In May 1969, when Jimmy was ten, William Roszko began to suspect Stephanie of infidelity. On the advice of a social worker, Stephanie attempted to leave her husband, but he refused to grant her a divorce on the grounds that it violated God’s commandments. A modern woman, Stephanie would not abide his attempts to control her, and abandoned him in February 1970 for a farmer named Marvin Prosser. Left with little choice, William finally consented to divorce. The ensuing court battle was an ugly, spiteful affair. Stephanie admitted committing adultery, but accused William of physically abusing her on a number of occasions. She also alleged he raped her when he was drunk, and that in 1969 he had pulled a gun on her when he suspected her of cheating on him. William maintained that Stephanie had fabricated these charges until his dying breath. For his part, he told the court that his wife was prone to drinking in town and would return in the evening acting surly and argumentative. Stephanie denied his accusations.

The level of animosity between his parents, coinciding with the onset of puberty, should have had a dramatic effect on Jimmy, although William said in court that he had “never seen him cry once.” Nevertheless, in November 1970, Jimmy visited his mother and her new lover, and decided he wanted to stay with them. Stephanie couldn’t resist taking a potshot at her ex-husband in court during her custody appeal: “He [William] pumped him so much [full of poison, that] I can’t control the child.… I need discipline from a man on this twelve-year-old child.… When [Marvin Prosser] just speaks to the child, he can get scared of the man.” Considering that in 1978 Prosser beat Stephanie within an inch of her life, this was unsurprising.

Always quick to figure people out, Jimmy moved back in with William. His father wanted the children to go back to church, but Jimmy refused. By now he was a highly disturbed grade nine student, who slumped over his desk staring at the floor. He appeared two years younger than his actual age; his complexion was pallid and his physique frail. When William caught the fourteen-year-old Jimmy with marijuana, he not only reprimanded him, but also contacted the RCMP. Jimmy flew into a rage, attacking his father in a wild fury until William had to physically drag him to the floor. Around the same period, Jimmy was lining his pockets by selling drugs and homemade moonshine. On one occasion he broke into a firearms store with some friends and made off with a rifle. An accomplice was nabbed for the burglary and squealed on them. That day, a man wearing the proud red uniform of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police knocked on William’s door to collect the rifle. From that day forth, James Roszko began developing a pathological enmity toward policemen, one that would ultimately culminate in his own demise. In the words of his lawyer, whenever Jimmy spoke of the RCMP his eyes lit up with fire.

Bad Things, Small Package

After the gun theft, William Roszko gave up on his son and avoided arguing with him altogether. Disciplining Jimmy became the sole responsibility of the police. Social workers intervened and fostered the wayward teen out to the Ziemmers — local farmers with a solid reputation. It wasn’t long before the patriarch, Herbert Ziemmer, realized that the “quiet, ordinary boy” entrusted into his care was absolutely self-absorbed. Jimmy denounced his brother John as a “square” when Herbert praised his sibling’s work ethic. Eventually, Jimmy unleashed a torrent of obscenities at the other Ziemmer children, and was sent back to live with his mother, her second husband, and Jimmy’s newborn stepbrother Douglas. However, while Stephanie had once been overjoyed at having traded dour old Bill for the tall, handsome Marvin, she now found herself wed to an even worse wife-beater who obsessed about her carrying on affairs with other men. On one occasion, Marvin battered her so severely that he fractured her skull, and Jimmy had to drive her to the hospital. According to William, his son began to fantasize about killing his stepfather. Fortunately for Prosser, Jimmy let him live. After Jimmy dropped out of high school in grade eleven, he divided his time between petty crime and legitimate labour, trying his hand as an oil worker.

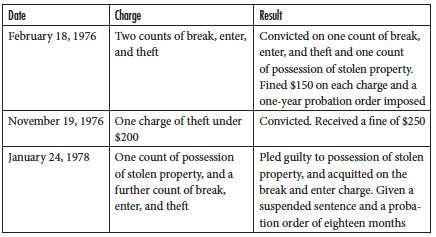

Jimmy’s criminal record began in earnest in November 1975 and continued until his death. Of all the surviving policemen who had run-ins with him over the years, veteran RCMP officer Mike Statnyk knew the depths of Jimmy’s evil better than any. In 1993, Roszko filed a formal civilian case against Statnyk for investigating him in the alleged sexual assault of several teenagers. Even though Statnyk was removed from the case, Jimmy continued to harass him, driving by his family home at all hours, and even conspiring to assassinate him. “Jimmy was always willing to step it up one. Jimmy crossed the line,” recalled Statnyk. “You know most criminals will respect a person, a member’s family … there’s boundaries that you as a policeman have, but there’s also boundaries that … criminals have. And … they know where to step and not to step.… I thought there would come a time when it would be a likelihood that I would probably have to shoot Mr. Roszko on my property out of fear for my life or my family’s life or safety.…” Statnyk echoed the statements of Jimmy’s stepbrother Doug and those of William and John Roszko: “Jimmy wasn’t used to being told.… He was used to getting his way.” Following the murders at Mayerthorpe, Alberta Justice Minister Ron Stevens requested that Gordon K. Wong, QC, conduct a review of Roszko’s past criminality. Wong’s

Report on James Michael Roszko: Prosecution History

, presented on September 23, 2005, reveals a versatile and extensive criminal career:

Table 5: The History of Criminal Charges against James Roszko

[48]