Rampage (8 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

By 1985, Peters was back on the streets of Sarnia, Ontario. His favourite haunts were strip clubs, where his handsome face and flirtation skills helped him bed many exotic dancers. The man with the blond hair and serpent tattoos soon earned a reputation for having a thing for handcuffs and S&M. Little did these women know the extent of his kinkiness. When he wasn’t feasting his green eyes on a stripper’s flesh, Peters was phoning local women and threatening to torture them and slice off their breasts. A police wiretap was put on two variety stores where female employees had received his menacing calls. Cashier Patti Armstrong remembers a voice on the other end of the phone hissing, “Women don’t have the right to live.” Yet Peters absolutely adored his mother — a fact which he made no secret of, whether to strippers or his fellow family members. In this way, he was like a laboratory ape, clinging to a wire substitute for nurture.

The Snake Swallows Itself

Though Peter John Peters originally refused to discuss his motivation for the London murder, police soon learned a vital clue from his former parole officer Natalie Black. For a time the two had been lovers, and she had helped him find his apartment and a position as a caretaker. Black had broken off her relationship with Peters two months before his crime spree, leaving him angry and dejected. He had attempted to temper his emotions by becoming romantically involved with Charlene Brittain. However, according to Detective Gary Harding of the London Police Service, Charlene had backed off when she learned of his criminal history. Peters pleaded with her to reconsider, but when she came over to his apartment to speak with him, they became engaged in a bitter argument. Unable to cope with the prospect of another woman abandoning him, he had decided to possess her in the only way he could: by strangling her to death. Of the Albert Philip murder, Peters said little, other than that he was in a “blind rage” and needed to steal a car.

Faced with twenty-nine charges from St. Catharines to Sault Ste. Marie, Peter John Peters travelled from one Ontario courtroom to the next, pleading guilty and recounting his frenzied crimes before a series of shocked jurors. As Peters sat in the prisoner’s dock, Sandie Bellows read an emotionally charged victim impact statement that reduced the judge to tears. When he asked Sandie if there was anything else she wanted to say, she turned to Peters.

“I would like to know why. Why you did this to me, John? Why did you feel you had to do this to me?” Peters’s response was surprisingly flat: “I don’t know.” When the dust cleared, Peter John Peters was handed three life sentences and shipped off to Kingston Penitentiary. The big bad wolf was not the only one who got what he deserved. For his bravery in rescuing Sandie Bellows, Alan Pike was awarded a citation by the Ontario Provincial Police. He was the first retired officer in the history of the organization to receive this honour.

While languishing in prison, Peters legally changed his name to John Cody, hoping to avoid notoriety in the event of his parole. He blew his chances in 2007 when, after seventeen years’ incarceration, the forty-five-year-old strolled out of Ferndale minimum-security prison east of Vancouver in British Columbia. At 5:20 a.m. the following morning, he telephoned the Abbotsford police department and asked them to pick him up. Back in custody, he was transferred to a higher-level security prison, where his day passes were revoked. Perhaps the beast had come to love his cage.

Despite both being lumped under the category of “rampage murderer,” Marc Lépine and Peter John Peters had drastically differing motivations. Whereas Lépine, a classic mass murderer, was determined to die and take as many “feminists” with him as possible, all but one of Peters’s spree crimes occurred primarily because he wanted to escape imprisonment.

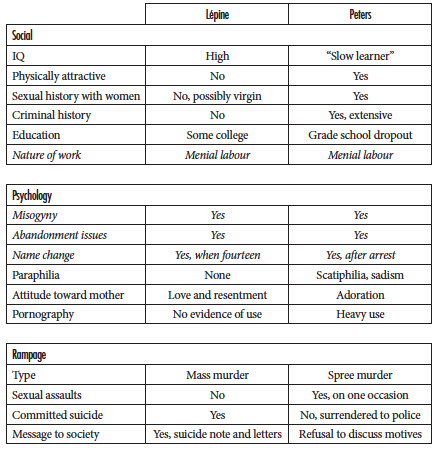

Table 3: Comparing and Contrasting Marc Lépine and Peter John Peters

Italics indicate a match.

*

Some sources say that Marc was fired in 1984. Perhaps owing to his mother’s position at the hospital, he was granted a second chance before blowing it again in 1987.

Chapter 2

The Problem with Boxes

One newspaper source consulted during the research for this book referred to

Peter John Peters

as a “sexual sadist,” an individual who “derives sexual excitement from the psychological or physical suffering (including humiliation) of the victim.”

[25]

Sadistic tendencies often develop in children who have been subjected to repeated physical or emotional agony, and who compensate as adults by inflicting pain upon another, thereby becoming the aggressor rather than the victim. Now that we have developed a clear understanding of the difference between a mass murderer like Marc Lépine and a spree killer like Peter John Peters, I will attempt to alleviate my own academic torment by irritating you with a series of “buts.”

According to the FBI’s

Crime Classification Manual

, the key difference between mass murderers and spree killers is the number of locations involved. The problem is that the authors do not provide a definition of what constitutes a location. Is it a room? A building? A street? City block? Neighbourhood? Small town? For this reason, some authors and criminologists have chosen to consider

Marc Lépine

a spree slayer, even though his “end game” psychology is more in keeping with that of a mass murderer.

The cases of

Rosaire Bilodeau

and

Robert Poulin

in this chapter exemplify mass murderer types whose multiple locations technically qualify them as spree killers. Rather, I refer to such offenders as “mass murderers with an overture.” In the two most category-confounding cases in Canadian history,

Swift Runner

and

David Shearing

committed all three types of multicide: spree, serial, and mass murder. For further annoyance, please review the cases of

Alexander Keith Jr.

(Chapter 3),

Marcello Palma

(Chapter 6),

Dale Nelson

(Chapter 7), and “Order of the Solar Temple” members

Joel Egger

,

Joseph Di Mambro,

and

Luc Jouret

(Chapter 9).

Glenbow Archive

Swift Runner

The Cree Cannibal

“I am the least of men and do not even merit being called a man.”

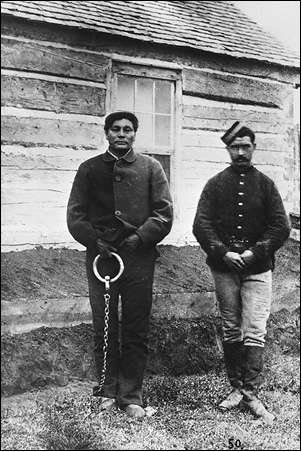

Swift Runner (Kakusikutchkin), shackled in Fort Saskatchewan.

Victims:

8 killed

Duration of rampage:

Winter of 1878/79 (difficult to classify)

Location:

Sturgeon Creek area, Alberta

Weapons:

Rifle, knife, hatchet, hanging

An Unpalatable Palate

In March of 1879, a hulking Cree man shambled into the Catholic mission in St. Albert, North-West Territories.

*

He said his name was

Kakusikutchkin

, or “Swift Runner” in the white man’s tongue — the last surviving member of his family. The winter had been a particularly cruel one; the buffalo, already thinned by unsustainable hunting practices, had been prevented from migrating north of the American border by a vast swath of burning prairie. When ten of the once prevalent creatures were spotted at Lizard Lake in the summer of 1878, the story made headlines.

Yet, considering the famine that had claimed the lives of his wife, five children, brother, and mother-in-law, at two hundred pounds Swift Runner looked surprisingly well-nourished. Dark rumours began circulating in the Native community. Though he appeared meek in the daylight hours, Swift Runner was plagued by horrific nightmares. He drew further suspicion upon himself when he attempted to lure a group of children away on a hunting trip. Noting signs of something sinister and familiar in his behaviour — quirks that may have gone unnoticed by Caucasians — several Cree reported to a local priest that Swift Runner was a “Windigo”: a cannibal killer possessed by a demonic spirit. The surprisingly open-minded clergyman contacted North-West Mounted Police Superintendent Jarvis in Fort Saskatchewan, and on May 27, 1879, Swift Runner was arrested under suspicion of murdering his family. Though he denied the allegations, the prisoner’s flat affect and contradictory statements failed to convince his accusers otherwise. He told of how his wife had become inconsolable, shooting herself dead after learning that their son had perished from hunger. The rest of his family had starved shortly after.

Determined to get to the bottom of it, Sergeant Richard Steele organized a small party to search the area 128 kilometres north of Fort Saskatchewan where they believed Swift Runner’s family had camped. Clapped in irons, the stolid Cree accompanied them along the trail in a Red River cart, his mind churning like the twin wheels through the prairie mud. As they neared their destination, he became belligerent and twice attempted escape. Rather than directing them to the camp, he seemed to be intentionally misleading them. Luckily, a guide named Brazeau had heard of Swift Runner’s penchant for

muss-kee-wah-bwee

— a concoction made up of alcohol and tobacco — which they used to ply the uncooperative prisoner. As the drink slowly took hold, Swift Runner lowered his guard, and slurred

“Wahabankee keezikow

,

”

or, “Tomorrow I’ll show you.”

The skeletal remains of Swift Runner’s family, brought in as evidence by the North-West Mounted Police.

The skeletal remains of Swift Runner’s family, brought in as evidence by the North-West Mounted Police.

Glenbow Archive

The next day, the drunken captive stumbled through the bush, followed closely by the RCMP officers. Upon reaching his destination, he raised his head to the sky and let out a blood-curdling howl. Nearby they found the remains of a camp: a teepee that Swift Runner had supposedly ingested had actually been folded and concealed in the undergrowth. Empty animal traps dangled from the branches. All around them was a garden of bones, picked clean by scavengers. Though Swift Runner attributed them to ravaging bears, the discovery of a child’s sock crammed into an empty skull suggested otherwise. Worse yet was the cooking pot laden with human fat. Overcome by nausea, several of the searchers hurried to empty their stomachs in the woods. The sound of vomiting was muted only by the cries of one enraged officer, who screamed a torrent of obscenities into the heavens. When the searchers had finally composed themselves, they set about the task of recovering the evidence. Swift Runner looked on drowsily as they filled their sacks with bones. What remains they couldn’t take with them they buried hastily before heading back to Fort Saskatchewan. Not long after arriving, Swift Runner confessed that he had “made beef” of his family. Poking his finger into the socket of a skull on Superintendent Jarvis’s desk, he muttered, “This is my wife.”

Transformation

There was a time when the “brute” had loved and been loved by his family. Born in a teepee on a blustery winter’s night, probably in 1839, the babe had been named “Swift Runner” several days later by an elderly shaman. The shaman had done so at a feast to honour the newborn’s arrival, during which each member of the community had taken turns cradling Swift Runner, reciting his name, and wishing him a life of happiness. For a time, fate had honoured their blessings. The child had grown up competent and carefree. As a young man he was proud of his proficiency in hunting and trapping, and his ability to craft weapons and snowshoes for wars against the neighbouring Blackfoot. Though something of an introvert, he was respected among his fellow Cree for his athleticism — combining his natural size and power with cat-like agility. While raiding a Blackfoot encampment, he had acquired a horse, a symbol of great status among his people. With his tall stature, good humour, and impressive achievements, he was able to easily woo a beautiful young woman named Sun-on-the-Mountain, and they soon fell in love. Typically there were arranged marriages in Cree society, but Swift Runner successfully broke with this convention when he brought Sun-on-the-Mountain’s father the gift of a horse. Sun-on-the-Mountain presented her suitor with a pair of moccasins in return. Upon his acceptance of her offering, they were married, and her people erected a new teepee.