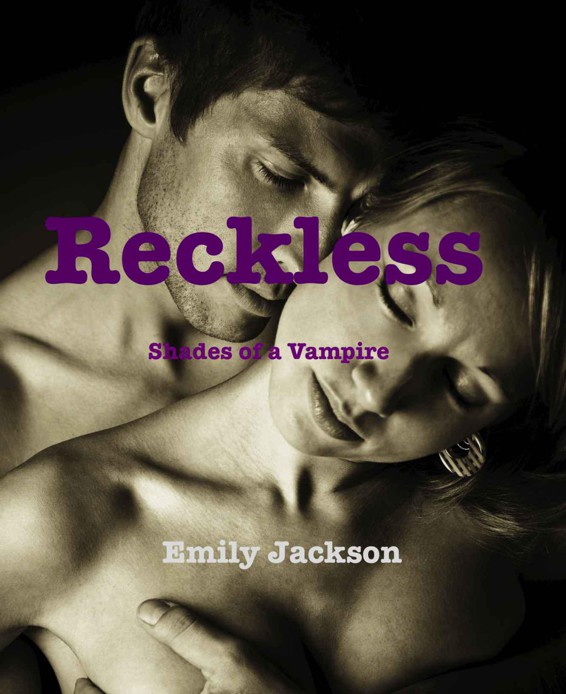

Reckless: Shades of a Vampire

Read Reckless: Shades of a Vampire Online

Authors: Emily Jackson

By Emily Jackson

Dedication

1. He That Spares the Rod

2. They Shall Speak With New Tongues

3. Emma Wants a Bite

4. Unless You Repent

5. Not Ready for Our Angel

6. It Bit Me Here

7. Calling You Home

8. Stillness in the Night

9. The Preacher’s Daughter

10. In the Shadows

11. The Sitting

12. Sunday Service

13. A Day of Thanksgiving

14. A Driver’s Education

15. Snake Handling

16. The Line of Duty

17. A New Year Arrives

18. Michael Returns

19. Knock at the Door

About the Author

He That Spares the Rod

Sprawled across the well-worn plank floor in a semi-conscious state, she even quoted her father’s words from a previous sermon, in verbatim and tone, which foretold her current predicament.

“

Then the lust

,” she heard her father saying from the pulpit, “

when it has conceived, bears sin; and the sin, when it is full grown, brings forth death

.”

She recalled the exact passage, hearing her father’s voice gather voluminous momentum the way a train’s sound does coming down the track. She exclaimed it to herself in loud internal solitude of affirmation.

“James 1, verse 15!”

Death, she thought. What a price to pay. She was just 18 years young, and barely that.

It was early summer. Not even two months had passed since her mother had sent away to the state for her home-schooling high school diploma. It had not yet arrived, but that was just a formality. Once the required coursework had been completed, she moved on to the next stage of her life without hesitation because she couldn’t conceive of an alternative. Nothing was complicated about it, according to her father's plan – no school meant more time for work around the house.

Before her last test was submitted, weekdays plus Saturday meant two hours of schoolwork and eight hours of chores. After, weekdays plus Saturday meant she had a full 10 hours for chores. Sundays were always a day of rest, and church. Her father viewed schooling as a matter of state law that had to be obliged, for the most part. He viewed domestic work and church as a matter of God’s law that had to be obliged.

Emma had learned reading, writing, and arithmetic, with her mother serving as more of a headmaster than a teacher, and Emma excelled to the point of wanting more exposure to each. But that was out of the question.

“They make us do too much already,” her father. “Too much of it is pointless. We learn from the Bible. The state should stay out of our business.”

Science wasn’t taught to Emma at all by her mother, though, even though the state did require that.

She passed the state’s final exam required for her home schooling diploma without ever studying science nonetheless, relying upon what she knew from observational learning, and what her mother called the “educated guess.” Common sense came easy to her, her mother often reminded, so Emma just applied it to the blanks left in the wake of her father’s insistence.

The Bible suited Emmaline Margaret Mays just fine. She just didn’t like how it served as a wall to the rest of the world for her, according to her father's convenience. She believed each and every word she had heard, or read, and she knew most of it by heart. By her calculations, she had either heard or read each of the scriptures enough to constitute seven or eight complete readings. She knew what the Bible said, and she knew what it meant. She just did not see why it had to separate her from everybody else so, and why her father had to use it to make her feel so bad.

Her father preached against lust, and told her gratification was wrong. Yet when the house was quiet at night, her chores done and her parents asleep, Emma could not help but slide down the covers, pull up her night gown to around her neck, moisten the tips of her fingers, gently rub the tips of her nipples until they became hard and tickled her clitoris, slid down her panties, lick the fingertips of her right hand, rub her pussy in slow circles at first, getting faster with each passing second, pinch her nipples in rotating fashion with left hand, dart a finger into her pussy, and come when she could not take any more until juices oozed onto her hand and sheets so hard she had to muffle grunts into her shoulder blade.

It felt so good she could not imagine how it could be wrong -- it wasn't hurting anyone, after all -- but that's what her father said. She tried not to do it every night. She thought about it every night. But she tried not to do it every night. Two to three times per week, she could not help herself, however.

"Her thing," is what she called it in her mind.

"I guess I'll do my thing," she would say to herself.

Or, "don't do your thing," if she had done it the night before and needed to talk herself out of it. Emma had done it as long as she can remember. When she was young, she did her thing by squeezing her thighs together at night. By the time her breasts sprouted and hair grew across her pubic bone, she had used her hand, tickling the spot she could mark hard, into a small sensational button.

Emma had wondered in days gone by of what it would be like living as others her age in the community. She had wanted to walk down the road with a boy on an early spring day when tender new flowers reached firmly up and the afternoon sun reached gently down, his hand clutching hers. Where they walked, or how long they walked, would not have mattered at all. She just longed for sweaty palms, a soft-touch sun, and flowers reaching up.

She wanted to make a new dress and wear it on a chilly, late fall night for a young man who knocked at the door, greeted her with a smile, took off his jacket, placed it around her arms, walked her to the car, opened the door, helped her in, closed the door, walked to the other side, got in the car, started the car, and looked at her and smiled with a fireplace warmth before driving off along a road to anywhere. She wanted to wrap her arms around him, have him thrust his tongue into her mouth. She wanted him to strip off her shirt, lick her nipples, pull of her panties, and thrust his erection deep into her and she buried her groan into his shoulder.

It didn’t happen that way, though.

Her father didn’t dream the same dreams she did on her behalf. And his will was her way in life. He had a plan for Emma that was to be followed, religiously. For Emma, that meant she was bound by an invisible leash that she could feel at all times, meaning she rarely veered far off the few square miles of winding county road that connected the parsonage grounds, where they lived, and Sand Mountain Pentecostal Church, where her father, Jeremiah Johnson Mays, was the pastor and only paid staff member.

A big trip for Emma meant going four miles down the road past the church to the biggest nearby town. Ider had a population of 664, but it was a metropolis to Emma, the biggest place she knew.

Home to the only post office and grocery market for miles around, Ider was the center of the community’s universe – a crossroads of commerce and connectivity for the mountaintop community.

Most children in the area attended Ider schools, which started in kindergarten and went all through high school. Ider High had sports teams and cheerleaders and even a 33-member marching band. Nicknamed the Rattlers, the school’s black and gold colors were painted on just about everything in town. Mailboxes. Storefronts. Pickup trucks. You name it. The Rattlers ruled Ider as the biggest game in town, outside of church, of course.

When she was 13, Emma prayed most every night for her father to let her attend Ider High School. But those prayers went unanswered.

“God did not make you to sit in a classroom all day,” he said. “Where in the Bible does it dictate that?

“

Women should be silent in the churches, for they are not permitted to speak, but should be submissive, as the law also says

,” said her father, quoting 1 Corinthians 14:34. “That means a women’s place is in support of man. You learn that in the home, and in the church. Not in a school building.”

On the leading edge of a string of small towns dotting the sandstone plateau that rises 1,500 feet above sea level in the northern reaches of Alabama known as Sand Mountain, Ider was also the biggest place Emma had ever been. With a population of 2,400, Henegar was four times bigger than Ider, and just nine miles south of the town on County Road 75. But though her parents went there every week or two on errands, she was never taken along.

They did not take her to Henegar; they did not take her along when they went in to Chattanooga, the Tennessee town of almost 200,000 people 43 miles away to the Northeast; they did not take her to Birmingham, Alabama’s largest city 115 miles away to the Southeast; nor did they take her to Huntsville, the Alabama town with a rocket ship factory that was 69 miles away to the East. The few times Emma had asked to go to Henegar, or beyond, she was reprimanded by her father with the accusation of parental disobeying that came with corresponding punishment in the form of lashes across the backs of her thighs with her dress pulled up to the elastic bottom bands of her panties so her flesh was struck with clarity.

“

He that spares the rod hates his son,”

said her father, quoting Proverbs

, “but he who loves him disciplines him promptly

.”

She wanted to tell her father that she was a daughter, not a son, since they were following the words so literally. But Emma knew that would only mean more lashes. So she stopped asking at the age of 15 to go along on trips to Henegar, or anywhere else beyond Ider. Emma pretty much stopped asking for anything.

The Mays family had just one car, a silver 1994 Ford Taurus that had stubs where seat belts once were. Her father had cut them out with his pocketknife the day they bought the car from a church member for $1,950. Emma's mother rarely drove, and Emma did not have a driver’s license, relegating her world on Sand Mountain to one small revolution, taken typically by either by the power of her own her legs or the family car, if and when her parents were inclined to give her a ride.

Typically, that was only to church, and back.

“You can walk most anywhere you need to go,” her father said.

He was right. She could walk anywhere she needed to go, since her home, the pasture out back, and the church up the road were the only places she needed to go or was allowed to go.

At home, most everything revolved around her father’s weekly sermons, from development to delivery, the family’s next meal, Emma’s chores, and bedtime. The Mays’ did not have a television set. They did not have a computer. They did not get a newspaper. She did not have an iTunes account, or an iPod, or magazines to read.

No makeup or curling irons were allowed. Boyfriends were out of the question, as were friends at all, really. Emma had a few peers at church she sometimes wistfully referred to as friends in conversations with herself and her parents, but she knew better.