Red Star Rogue (3 page)

Authors: Kenneth Sewell

T

HE

C

OLD

W

AR SAGA

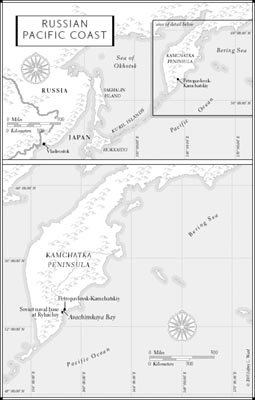

of the Soviet submarine known as K-129 began two months earlier, on the fog-shrouded Kamchatka Peninsula of the Soviet Union’s Pacific Far East. In the first week of January 1968, the diesel-electric, ballistic missile submarine returned to its base from one of its autonomous missions, a seventy-day patrol somewhere in the North Pacific.

These lengthy assignments were called “autonomous” because the submarines were sent out alone, with sealed instructions meant for only two people, the captain and the political officer. After sailing, a boat would limit communications with headquarters to coded microburst transmissions when it reached specific, predetermined locations along its course.

K-129 had departed on such a mission in late October 1967, and returned to home port after the successful conclusion of the assignment, on approximately the sixth of January 1968.

The submarine sailed in from the open Pacific and entered Avachinskaya Bay on the southeastern coast of the Kamchatka Peninsula. The huge deepwater bay had provided safe harbor for Russian sailors since the 1600s, serving as an unconquered Pacific outpost for czars and commissars alike, in wars against the British and French in 1854, the Japanese in 1903 and 1945, and finally, against the United States Navy in the protracted Cold War. At the time of this incident, that global stalemate had already lasted two decades.

K-129 returned to the windswept bay not far from where it had submerged to begin its clandestine mission two months and ten days earlier. The submarine surfaced near the Three Brothers Sea Stacks, the natural rock formation that stood sentinel at the bay’s entrance. In the morning light, the base of one of the volcanic peaks, 3,456-foot Mount Koryakskaya, could be seen looming behind the port city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy. The mountain’s peak was covered by clouds and fog during most of the winter months.

The captain, wearing a sheepskin coat and an expensive fur

ushanka

covering his head, appeared at the bridge atop the submarine’s high sail. A seaman, also dressed in a heavy woolen coat and headgear, but not of the distinctive fur and sheepskin worn by senior officers, hurriedly took the ship’s Soviet navy ensign from a locker in the action center of the conning tower and followed the captain to the bridge. The young seaman attached the flag to the ship’s mast.

A strong north wind snatched the flag from the sailor’s arms and unfurled it in a flapping streamer over the conning tower. He rendered a smart salute and proceeded to his lookout post. The flag’s bright colors—a large red star leading the red hammer and sickle on a white field above a sea-blue stripe—were in stark contrast to the wintry gray waters of the bay, eroded brown shoreline, and snow-covered hills and mountains. The wind snapped the flag briskly above the submarine as it plowed at fourteen knots through small whitecaps on the surface.

The temperature hovered between a seasonal norm of 10° to 12°F, but the biting cold was welcomed by most of the crewmen gathered on the bridge. For them, it was a physical release to take the first deep swigs of open air, no matter how numbing the chill. It was an even greater pleasure to see the familiar landmarks along the bay shore for the first time in more than two months.

The man in the distinctive fur hat was Captain First Rank Vladimir Ivanovich Kobzar, one of the most competent and respected officers in the Soviet Pacific Fleet. At age thirty-eight, he was already a seasoned submarine commander and had captained the K-129 for three and a half years.

Before the waters brought up from the deep were fully drained from the deck, sailors had opened the hatch above the aft torpedo room. Even on this overcast morning, the men’s first glimpse of sky caused them to squint sharply against the light.

Almost as soon as K-129 surfaced, a small tugboat that did double duty as an icebreaker signaled, “Follow me.” The auxiliary boat, sent out when K-129 radioed flotilla headquarters that it was entering the bay, had been waiting to escort the sub. It would lead K-129 through the thin ice shelf that formed along the shore all winter, and into Rybachiy Naval Base. While the open waters of the huge bay were largely clear of ice, the shorelines remained ice-bound from late autumn until the middle of spring. The tug led the submarine into Krashennini Cove at the southeastern end of the bay and crunched a path through the ice shelf to a center berth that had been reserved for the arriving sub.

The docking area consisted of twelve long, concrete piers that made up Rybachiy’s main submarine pens. Other submarines, some much longer and wider than K-129, were secured in the shelter on either side of the piers. The facility could easily hold four dozen submarines tied up at one time. Just inland, adjoining the piers, were concrete warehouses and industrial buildings where supplies were stored and machinery hummed with constant demands for spot repairs on the fleet. The concrete docks, buildings, and treeless muddy yards all blended into a muted gray that echoed the drab hues of the idled submarines.

While the tug gently nudged the K-129 into the assigned berth, a small knot of grim-looking officers in black greatcoats watched from the pier—the only reception party. Unlike its American counterpart, the Soviet submarine service did not encourage families and friends to greet their returning submariners.

The crew was required to remain on board while the captain, first officer, and political officer reported to the division commander. Only after a brief report on the mission had been satisfactorily delivered could the captain return to the boat to allow the first of the crew—those officers and senior petty officers with family members billeted nearby—to depart the boat. If anything at all had gone wrong on the long mission, no one would be allowed to leave the submarine until the chain of command was fully satisfied that all questions had been answered. Even the wives of the most senior officers were not informed of K-129’s return until this debriefing had been completed to the satisfaction of headquarters.

There had been many cases, particularly during the unsuccessful ventures of Soviet submarines to Cuba during the 1962 crisis, when submariners were confined aboard their boats for weeks after returning from months at sea. Often this cruel, extended confinement had been imposed for minor infractions that were no fault of the seamen and officers, such as being forced to surface for identification by harassing U.S. Navy destroyers. The Americans would stalk the submarines, pounding them with their powerful active sonars. They positioned their warships over the Soviet subs to prevent them from snorkeling to recharge their batteries or replenish their air. Ultimately, the sub commanders had no choice but to surface. The Soviet admiralty blamed the crews and officers all the same.

The ice surrounding the pier had offered little resistance to the K-129, cracking into sheets that rode up on the curved pressure hull as the sub came to rest against the rubber bumpers of the concrete pier. Sailors wearing life jackets over winter coats caught the knotted lines thrown by the men on the pier. These ropes were attached to the heavier mooring lines that would secure the sub.

The seamen kept busy as they waited for their captain to return. The deck of the submarine was a beehive of activity as men set up safety lines and engineers worked at connecting the heavy auxiliary cables that would supply the submarine with electrical power while in port. A gang-way had been hoisted from the pier to the deck, but nobody dared cross it. They wouldn’t have to wait long, anyway. The crew was certain there would be no extra confinement this time—the mission had gone without incident.

The eighty-three crew members had every reason to expect a well-deserved six months in port, with only brief coastal drills and routine maintenance and repair work until midsummer, when they would sail again.

Concrete submarine pens lined the entire south shore of Krashennini Cove, a bristling arm of naval activity off the larger bay. The cove provided slight relief from the strong winds that occasionally lifted the low clouds for brief views of the snowy peaks. In midwinter, at this latitude, there were just four hours of gloomy daylight, made even grayer by the incessant fogs and scudding low clouds off the Bering Sea. Rybachiy was less than 750 miles south of the Arctic Circle.

When the north winds were strong, waves lapped over the decks of the boats tied up at the concrete piers built low to the water to accommodate submarines. Wet and icy in patches, the decks appeared a darker gray than the looming conning towers and launch tubes encapsulated behind them.

The submarine base was located across the bay from the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, the capital of the Kamchatka

oblast.

With a civilian population of three hundred thousand, it was the largest city on the 470,000-square-mile, mostly wilderness peninsula. Naval yards, military camps, and KGB border-guard stations dotted the bay shores. Because of its secret installations, the region, including the city of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, was closed to everyone except Soviet citizens and visiting allies. Commercial fishing was the only nonmilitary economy of the region. Even then, the ostensibly civilian trawlers of the fishing fleets doubled as military intelligence boats.

This fogbound bay sheltered the submarine pens for the deadly Kamchatka Flotilla, to which K-129 was assigned. The facility, exclusively dedicated to the dispatch of Soviet missile and attack submarines, was one of the most guarded installations of the Soviet navy.

By the mid-1960s, Avachinskaya Bay had become the Soviet Pacific Fleet’s most important submarine center. It was a major naval asset in the Communist giant’s mighty striving to compete with the rapidly modernizing United States Navy.

The Soviets had struggled for the first decade of the Cold War to meet Joseph Stalin’s impossibly audacious military goal of building the world’s largest submarine force. The Soviet dictator believed that the outcome of World War II would have been far different if Hitler had invested more of Germany’s resources in submarines. In the early 1950s, Stalin ordered more than twelve hundred submarines built.

Although that grandiose plan was abandoned at Stalin’s death in 1953, his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, saw the submarine service as an essential part of the Soviet military strategy and placed an emphasis on upgrading the Red Navy with fewer, but more modern, submarines.

Construction of nuclear-propelled, ballistic missile submarines was once again given top priority when Leonid Brezhnev assumed power after a Moscow cabal ousted Khrushchev in 1964. Admiral Sergey G. Gorshkov, commander in chief of the Soviet navy, believed that nuclear submarines were best suited to lead the way in the development of the Soviets’ new blue-water navy.

However, the naval construction program, along with rapid expansion of land-based intercontinental nuclear weapons, was crippling the economy of the Communist behemoth. The Kremlin was expending as much as 60 percent of the country’s gross national product on military and space budgets. The Soviet people knew only that their shoes were ill-fitting and the shelves were usually empty at the cooperative stores.

Despite this huge military outlay, the Americans continued to outpace the Soviets in construction of nuclear weapons and the missiles, ships, and aircraft needed to deliver them. More important than numerical superiority was the quality of the weaponry. The United States was producing more technologically advanced, longer-range, multiwarhead missiles and a new generation of nuclear-powered submarines.

The bellicose rhetoric of Kremlin politicians did not fool everyone. A few Moscow economists already knew the Communist system of centralized control had failed to live up to expectations and stood no chance of competing with modern Western economies. Many generals and admirals in the Soviet Union watched the rapid modernization of the U.S. Air Force and Navy with growing apprehension.

To counter the widening nuclear weapons gap, Kremlin strategists pinned hopes on what they deemed to be America’s greatest weakness, the inability of Americans to sacrifice their people for the good of the collective. They knew Americans could never face the terrible prospect of losing even a single city to a nuclear attack. Soviet leaders based their beliefs on observations of American battle tactics during World War II. On the battlefield, U.S. commanders favored maneuver and firepower over frontal assault to achieve victory. The public outcry over casualty figures in Vietnam seemed to verify their assumptions. Some cynical leaders in the Soviet Union believed that as long as they could guarantee the incineration of just one U.S. city, it would be enough to hold the American hawks in check.