Reign of Madness (19 page)

Authors: Lynn Cullen

The Spains

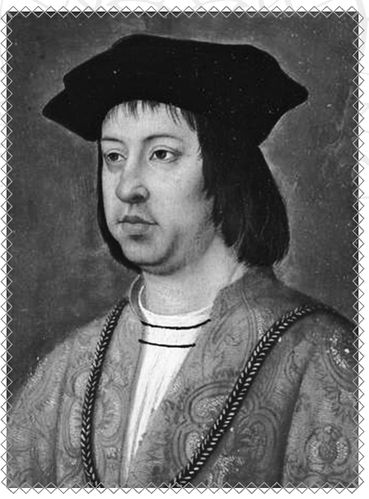

Fernando of Aragón

22.

26 January anno Domini 1502

F

lickering torchlight dabbled shadows on the walls of the castle as Philippe drank another glass of wine under the inquisitive eyes of our host, the Marquis of Denia.

“Not bad.” Philippe smacked his lips. “In my lands, it is a touch more rich. But not bad for wine, not bad.”

Denia, a young dandy with a great dark curl pasted onto his forehead, watched with stunned interest as Philippe drained his cup. No doubt the last person he had seen drink with such thirst was a plowman, tipping back a skin in the fields. It was our third day in the Vizcayan town of Segura, and Denia still regarded my husband with the unbelieving fascination one might have, should a satyr come to supper.

“I am glad that you find the wine acceptable,” said Denia, “as you will now be residing in our lands.”

Philippe lifted his brows at me over his cup. We had come to the Spains only for me to receive confirmation as rightful heir to the throne, with Philippe as my consort, legal foolishness to which I agreed so that my Charles could inherit the throne someday. For once, we were in complete accordance: neither of us had any intention of staying any longer than for the Cortes to convene. We could not hasten back to Flanders quickly enough—I to the children, and Philippe to Delilah and the hunt.

Denia’s eyes, as large and liquid as a bull’s, registered heightened interest as he noted our exchange of glances.

“I did like that joust with the darts.” Philippe put down his cup. “What did you call it?”

“Jugar a las cañas.”

Denia switched back to French. “It is Castilian for ‘to joust with canes.’ ”

“Good name.” Philippe stabbed a portion of meat from the platter before him, nearly grazing the back of his hand on one of the serpents’ tongues of the poison tester brought from Flanders and dutifully set before him by his cupbearer. “

Cañas

. They might have just been canes, but those devils were sharp.”

“That is why we have shields.”

“No jest. People are not shy about flinging their canes. Still, I liked it. Let’s do it again tomorrow.”

Denia’s glossy curl swung forward as he bowed his head. “Permit me to substitute a running of the bulls instead.”

I sighed. Our first stop in Spain, and already we were obliged to stay for several days, days in which baby Isabel, now six months old, might be cutting a tooth or Leonor might be having a nightmare and needing comfort.

“Bulls?” said Philippe. “Excellent. I have always wanted to see this Spanish sport.”

“Ah yes, I hope that His Highness enjoys it. And I understand there is quite a surprise being planned for you in Miranda de Ebro.”

The pouches at the sides of Philippe’s mouth lifted. “What?”

Denia and his curl bowed again. “It would not be a surprise if I told you, but I assure you, you will like it.”

“I will like it more if there is good Flemish beer.”

To Philippe’s left, Hendrik laughed.

Denia allowed himself a small smile.

Poor Hendrik, so coarse and thickly Germanic—he stood out in this elegant crowd. Not so the Archbishop of Besançon. He speared his meat with great delicacy while leaning toward Denia’s wife, lending his ear with a cold, hard grace as she prattled on. I gazed around the crowded hall, loud with conversation and the clink of plate and spoon. Ladies and gentlemen sat at tables, the jewels on their bright silks winking in the torchlight. I could recall few dinners in the Spains attended by both ladies and gentlemen. Was the custom different in this area? Indeed, the nobles were dressed more elegantly than I remembered Spanish nobles to be. Two years before I had left the Spains, Mother, under the influence of her confessor, Cardinal Cisneros, had decreed that only grandees could wear colored silks and gold trims, and not even they could wear colored coats to match. But everyone in this assemblage was dressed as splendidly as a peacock. The laws in this land must have been different from those in the rest of the Spains.

“Would you like beer?” said Denia. “I shall make sure to find a brewer.”

“Oh, I have a brewer,” Philippe said, speaking through a mouthful of beef. “He is part of that pack of two hundred–some persons milling around your courtyard, among them my tailors, my glover, and my soapmaker. People I cannot live without. Oh, and Juana’s washerwoman. My wife

would

have her, though I don’t know why.”

Perhaps because she was one of the few I could afford to pay after pawning the little necklace my sister Catalina had once sent? “How long will we be in Miranda de Ebro, señor?” I asked.

Philippe answered for Denia. “As long as our hosts would have us. Don’t tell me you’re in a hurry to see your mother, Juana.” He swallowed, watching me. “Are you?”

Denia smiled politely. “Their Majesties are journeying from Granada, Your Highness. I understand you will meet them in Toledo.”

“Yes.” As much as I wished to hurry this visit, I was in no rush to meet my mother. Indeed, whenever I thought of it, a knot tightened in my stomach.

“Allow us to entertain you this evening. A little performance is about to begin.” Denia picked up a golden bell next to his plate and, dipping his curl, held it to me. “Doña Juana?”

I shook it. At its golden jingle, wildmen bashed open the doors and stormed into the hall, shaking rattles made of bones and shouting gibberish. Eyes crazed behind green-feathered masks, they ran around the tables with loincloths flapping, making the ladies scream. One shook his rattle in my face, then jumped on the table.

Philippe sank back in helpless laughter as others leaped onto the table, spilling cups, knocking plates, scattering food. “Oho! What denizens of Hell are these? Watch out—he’s going to get you, Puss!”

The door to the hall banged open again. In rolled a mock carrack on wheels, accompanied by dancing boys dressed as dolphins and pipers in blue. On the quarterdeck of the pretend ship, swaying to and fro as the wheels creaked across the rushes, a tall and portly player searched the horizon through his spyglass. When he saw the wildmen cavorting on the tables, he called out, “In the name of Their Sacred Majesties Doña Isabel and Don Fernando, I, Cristóbal Colón, the mighty Admiral of the Ocean Sea, claim you as my subjects.”

The wildmen abandoned their tormenting of us. Brandishing their bones, they hopped down and swarmed the base of the ship. Three sailors rushed to the bow, then heaved a net over the frantic creatures.

“Look what God has given me!” proclaimed the actor playing Admiral Colón.

The crowd cheered, even the ladies. I looked around. Since when had ladies cheered at supper in the Spains? Since when were the entertainments so lavish? What had the Spains become in my absence?

The sailors hauled their writhing load aboard, and all disappeared into the bowels of the ship. Then Admiral Colón gave a speech about his special favor from God, puffing out his chest much like the real Colón of my childhood, to the sportive jeers of the crowd.

The wildmen reappeared on the quarterdeck, this time in chains, goaded by the boasting Colón. As they clinked their bonds and wailed their laments, another ship heaved into the hall. At its helm was another play-actor, scanning the horizon with his spyglass.

He snapped it closed when he saw Colón. “In the name of Her Majesty the Queen Doña Isabel and His Majesty the King Don Fernando, I, don Francisco de Bobadilla, claim

you

as

my

subject.”

Francisco de Bobadilla? In the true world, he was Mother’s good friend and a trusted public servant. I had known the kindly gentleman since I was a child.

The mock Bobadilla produced a weapon from his scabbard. He swung from a rope and landed with a thump on the deck of Colón’s ship. Swords rang out as the players fell into a fight.

Philippe leaned toward Denia. “This is almost as much fun as the entertainments in my court,” he said over the clanking, “though it lacks the naked girls.”

Long lashes a-blink, Denia stared at Philippe as the play Bobadilla forced the weapon from Colón’s hands. With Colón’s sword still clattering on the floor, Bobadilla commenced wrapping the Admiral in chains.

Our host returned his sights to the players as Bobadilla displayed his conquest to the crowd. “Look what God has given

me

!”

The crowd shouted as if at a running of bulls. The players rolled away on their ship, Bobadilla with his sword drawn over Colón, the Admiral gaping at his chains.

Philippe stood up, clapping.

“Señor,” I asked Denia, “what is the meaning of this play?”

He looked at me in surprise. “You do not know about the Admiral of the Ocean Sea?”

“My sisters told me he had returned to the Indies.”

“Oh, he came back, Your Highness. In chains.”

“He came home in chains? When?” Why had María not written to me about this?

“Let me see,” he said, “it was November, a little over a year ago.”

That was about the time María had been wed to the King of Portugal. The summer before her wedding, her letters had been full of breathless descriptions of the clothes being made for her, of the furniture she would take, and of her hopes that her husband would be dashing. Then, after her wedding, silence. It would be six months before I heard from her again, and by then it was no longer my dear, dreamy María who wrote. Whether it was her pregnancy or something else that caused her letters to become terse and short, she was no longer given to reports about the handsome sons of sailors.

“It was a matter of great amusement for the blustering fool to be brought so low.” Denia looked at me closely. “But do not fear, Your Highness. The Queen had his chains removed immediately and restored the properties Bobadilla had stripped from him. In fact, she has granted him ships and money for another voyage, though he is to avoid Hispañola, where he made a great mess of the place. The colony was in an uproar when Bobadilla got there—Colón was hanging good Spanish men left and right for insubordination, and selling Indio slaves by the boatful though they weren’t his to sell. It seems, Your Highness, that while Colón has a gift for the sea, he has not an inkling about how to deal with men.”

Philippe glanced at me as I sat back, deflated. As much as I had scoffed at the windbag, seeing him brought low disturbed me. I cringed for Diego. He had been so proud of his father, seeming to tether his own worth to his father’s star. The chains on the father must have weighed equally heavily on the son.

Trumpets sounded; bows were taken to violas da gamba; a shawm bleated as a player tried his reed. A tambour was beaten three times and the music commenced.

Denia and his curl bowed in full deference. “It is time to dance, Your Highness.”

Philippe grabbed my hands and pulled me from our bench. “I had Spain all wrong. Hendrik, grab a lady and get out here.”

The Archbishop of Besançon watched me with expressionless eyes, then called to his scribe. The young fellow hurried over, wiping his mouth, then took out his writing case.

23.

19 February anno Domini 1502

I

t was one of those winter days in Burgos when the sky was so blue and the sun so brave that you almost did not mind the season. Our horses plodded along the path by the river, their hooves thudding against the thick layer of rotting leaves over which yellow silt had been churned. The lilting song of blackbirds mingled with the hum of the rushing water.

“If I play one more game of tennis,” said Philippe, “I swear I shall drop.” He looped his reins around the horn of his saddle and with a groan stretched his arms over his head. His horse, Helene, his favorite ambler, brought with him from Flanders, needed no reins or guidance. She intuited where her master wished to go—a handy talent for a horse who had often to take her master home when he was senseless.

“You needn’t play so much.”

“And let Pedro show me up? No, thanks.”

Since arriving in Burgos three days earlier, Philippe had discovered that Pedro Fernández de Velasco, the seventeen-year-old son of our host, Iñigo Fernández de Velasco, brother of the Constable of Castile, shared a passion for winning. They found tennis to be an agreeable field of contest and, each hoping to prove himself champion, slogged through matches day and night. Thus far they had won an equal number of games, and so their rematches went on. One of them had to concede to the other, something obviously not in their natures. Evidently Don Pedro had not received the missive that everyone else seemed to have received here in Spain, that my husband was to be spoiled and given his way. We could be in Burgos for weeks, proving who was the victor with the racquet, while at home, baby Isabel was learning to creep on her belly and Charles was speaking in sentences. My poor little boy with his overshot jaw, would his nurses understand him? Would he say, “I want milk,” and be given a toy and left thirsty, without his mother’s patient ear to hear him?

A green heron was startled from the bulrushes at the water’s edge. It flapped over the pale bobbing tufts toward the town. The towers of the cathedral could be seen in the distance.

“By God,” said Philippe, watching the bird, “I wish I had Delilah.”

“Let’s go home and get her.”

He gave me a bemused look as he took up his reins.

“Might we return to Flanders soon?” I asked.

“I thought Castile was your home. Anyway, we should enjoy this place while we can.”

And enjoy it he did. In Vitoria he delighted at the bull run held in the city streets. He cheered at the bulls’ scrabbling on the cobblestones, and laughed at the children scrambling out into the road between bulls to fetch the sweets he had thrown there. He roared with happy trepidation when a bull approached and a child still hunted a morsel that others had missed. He did not understand why I left, upset, though the child had been unhurt.

In Miranda de Ebro, he clapped like an excited boy when a hundred horses thundered past the palace, the scarlet capes of their Moorish-dressed riders whipping in the wind. When a hundred armored horsemen rode up crying, “

¡Santiago y cierra, Espana!”

and engaged the turbaned riders in mock battle, he begged to join in. He was given chain mail and a warhorse and turned out onto the field, where his cries of “

¡Santiago!

” soon blended with the herd.

At least now in Burgos his energy was bent on a cloth ball, endangering neither men nor children, nor himself. Relaxed and cheerful from his exertions, he had agreed to accompany me to the Carthusian monastery of Miraflores on the outskirts of town—as long as we prayed little and left quickly.

Beyond the bulrushes, the Arlanzón flowed intently. Sticks, leaves, someone’s glove—all were hostage to its mission to join other waters to reach the sea. The air smelled of wet plants and earth and the cold.

“Philippe, why don’t we send for the children?”

“And risk their lives on the roads through France?”

“They can sail.”

He gave me a look.

I did not truly think to endanger them in such a manner, either. I sighed. “I miss them.”

He chirruped to his ambler. “What is so special about this monastery that you are dragging me to? Couldn’t we just hear Mass at the cathedral? It’s a big-enough place.”

I trotted after him on my horse. “Miraflores is the burial place of my grandparents.”

“It’s a beautiful sunny day and you’re taking me to see tombs? What did I agree to?”

“They are no ordinary tombs. Mother ordered them built when I was young. They are just now finished. The sculptor was Flemish.”

“Of course. All good carving is Flemish, though I suppose the tombs won’t be as nice as my mother’s.”

“Probably not.”

He reached over the back of his saddle to me. “How about a roll in the rushes?”

“As appealing as that sounds, Monseigneur, no.”

His pretty lips turned down, puckering the pouches by his mouth. “What happened to you? You would have jumped at the chance when we first married.”

When we met I did not have three children. When we met I had not grown up while he had stayed a boy. When we met, I did not know that he thought a husband’s infidelities were harmless, that a wife was foolish to let them bother her, when that is just what men did. But in spite of all this, should he stop our horses and take me in his arms, with some coaxing he could mold me to his purpose. A few kisses to the neck, the feel of his breath on my ear, his lips upon my flesh, and given time, my body would betray me. Perhaps that was merciful. How would this man who lived by the word “yes” respond to a heartfelt “no”?

The path led up a wooded hill cloaked in waist-high grass, which hissed as it bent under our horses’ bellies. Above us, tufteared black squirrels leaped from tree to tree. I freed my skirts from the canes of a wild rose.

“It’s not far now,” I said.

Philippe frowned at the stone walls of the monastery now visible through the woods. He snorted with exasperation. “Let’s get this over with, then.”

The Royal Chapel smelled of cold marble. A chill emanated from the pale limestone floor, from the rough-hewn walls of granite, from the white alabaster tomb before us that bristled with dozens of masterfully carved saints and animals. How had the sculptor teased these beings out of stone? They were lifelike down to their individual expressions, to the very hairs upon their gleaming heads. Their magnificence was matched in the carved wooden altarpiece looming overhead. The saints and angels—and Mother, kneeling in the foreground—were drenched in brilliant gold.

“Juan the Second, King of Castile.” Philippe leaned against the intricately wrought gilded fence that surrounded my grandparents’ tombs. His voice echoed from the vaulted ceiling. “Was he a good king?”

“He was my mother’s father.”

“But was he good?”

I gazed at the robed figure reclining on the sarcophagus of whitest alabaster. His crowned head rested on a stone pillow; a stone dog slept at his feet. Beneath him, a lion roared, a wafer-thin alabaster curl of tongue lolling between its teeth. “He had a favorite whom he let rule while he played at his jousts and hunts and tourneys. Álvaro de Luna. He ran Castile for my grandfather.”

“That’s unwise.”

“Most unwise. Atrocities happened right under Grandfather’s nose, but he could not see this. If people complained to Grandfather, Luna had them killed. He poisoned Grandfather’s first wife when she tried to sound the alarm, and still Grandfather did not see. He was too busy . . . hunting.”

Philippe ran his hand along the fence rail, then inspected his finger to see if any gold had come off.

“Grandfather trusted him completely,” I said. “Luna was like a father to him. Grandfather’s own father had died when he was a toddling child, and Luna became his tutor.” I glanced at my husband. Did he not see the resemblance to his relationship with the Archbishop of Besançon?

He looked up. “Go on.”

“Luna was a hated name around our home, for making my grandfather look foolish, but even more so for what he did to her.” I nodded to the marble figure lying next to my grandfather.

“Isabel of Portugal,” he said. “The mad one.”

“Who told you that?”

“Everyone.” He shrugged. “Grand-mère. François. It’s no secret that your grandmother was

zielsziek

.”

“But she wasn’t, unless it was madness to challenge a monster like Luna. When she tried to tell Grandfather that Luna had murdered the first queen with poison, and that Luna threatened to poison her, too, if she tried to expose him, Grandfather wouldn’t listen. He couldn’t imagine Luna as anyone but the kindly father figure who had bounced him on his knee.”

“So did this Luna kill her?”

“You don’t have to kill to do damage. He gave her just enough poison each day to sicken her. When Abuela was ill from the poison, he spread rumors that she’d gone mad, and she was too sick to refute him.”

“But she got well?”

“Yes.”

“Then why did she not simply tell people what he did?”

“She did. But it was too late. Her reputation for madness was sealed. It seems that an accusation is as powerful as the truth—once it is made, there is no denial that can completely erase it.”

He looked at me a moment, then, grasping the finials, stared at the tomb. After a time he asked, “How did he administer this poison?”

“I don’t know. But it was enough to temporarily damage her mind.”

The bells of the monastery now began to clang, slowly marking the hour as if it were Time’s last. I could feel the vibration under my skin.

Philippe pushed away from the fence. “Well, sad story, Puss,” he said, raising his voice above the bells, “but Pedro will be waiting. I’ve got ninety pieces of gold riding on our match. Have you seen enough?”

I drew in a breath, shaken somehow. My poor grandmother. No matter what she had ever said or done, she would be known to history as mad. How awful it must have been for her to endure the false smiles on people’s faces as they privately discounted every word that came from her mouth. Perhaps this had made her mad in itself. How does one keep one’s sanity after decades of being disbelieved?

Philippe glanced at the lovely tomb carved into the wall behind us. Above the booming bells, he asked, “Who is that?”

“Alfonso. My mother’s brother. The prince who was supposed to be King. He died when my mother was a maiden.”

The bells stopped, though the sonorous reverberations continued in my ears.

“So there lies the true King of Castile,” said Philippe.

“If he had lived, yes.”

He cocked his head, appraising me as if I were a stranger to him. “Odd, how things work out. He was supposed to be King, but your mother ended up with the crowns. Your brother, and then your sister, and even her son, were to be your mother’s heirs, but here you are, next in line.”

“And you.”

“Not really. In this land I am only to be your consort, not truly King.” He took my hand and kissed it. “But you never know, do you?”