Reign of Madness (31 page)

Authors: Lynn Cullen

England

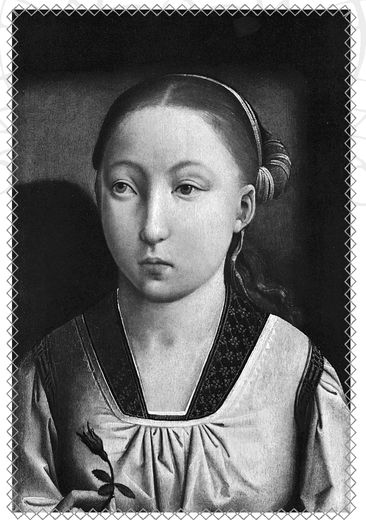

Possibly Catalina of Aragón

40.

12 February anno Domini 1506

M

y fur sleeves brushed against my gown as I held out my arms. “Sweetest Catalina!”

My sister hesitated for an almost imperceptible moment, then launched herself across the frigid stone chamber within the forbidding English castle at Windsor. “Juana!”

We rocked each other in an embrace, then held each other out. How lovely my youngest sister had become. At twenty, there were no more gummy smiles, no trace of her girlish awkwardness. She had my mother’s thick red-gold hair and Papa’s well-shaped lips and a sparkle to her blue eyes that was all her own. It was hard to imagine that this vibrant young woman was a widow—she had lost her husband, the King’s son Arthur, when she was sixteen. It was even more difficult to believe that another prince had not claimed her as his bride.

“You are well,” she said wonderingly.

“Yes.”

“I am so glad!” She hugged me to herself again. I drank in her oily-sweet smell, familiar to me since childhood. She let me go and beamed at me. “Thank God you are well.”

“You act surprised.”

“Your husband said—” She stopped, blinking blond lashes.

“Said what?”

She shook her head. “When you did not come to meet the King upon first reaching our shores—”

“I wanted to come. I wanted to see you! Philippe—” I took a breath, remembering how, the day after we had arrived, I had found the door to my chamber locked from outside when I had dressed, only to learn that Philippe had galloped off without me. “Philippe detained me.”

She smiled apologetically. “He said you might say that.”

“What else did he say?”

“Nothing, really. That you’d had a small incident that prevented you from accompanying him just then, that was all, but that sometimes, unfortunately, you were—”

“What?”

“I’m sorry—given to flights of fancy. But who isn’t?” she added hastily. “After Mother died, I kept thinking I saw her at the window, but when I opened the casement, it was just a bird. Indeed, I went quite mad from my grief. I cried for days on end. None of us were there when she passed from this world, Juana. Not even Papa. It makes me feel so terrible. She did not deserve that.”

Tears flooded my eyes. I had not known that Mother had died alone. No one had told me. To think what must have gone through her mind, abandoned, in her final hours.

She wiped at her eyes. “Only Fray Hernando was there.”

I looked up. “Fray Hernando?”

“He had come from Granada for the last few months of her life. I suppose that was a comfort to her.”

I thought of Mother’s reply that day of her first illness, when I had remarked that Fray Hernando, as the holiest of men, cared not for earthly power.

No,

Mother had said.

He doesn’t. He cares for me.

“Yes,” I murmured, “I suppose it was.”

“Well, I don’t know what is wrong with Papa. I shall not forgive him for marrying that girl. Mother was hardly cold in her grave! Have you met her?”

“Germaine of Foix? Yes, at the French court.”

“What was she like?”

I winced, remembering that awful visit, where I had been abandoned by Philippe and left to fend for myself with the Queen’s hostile court. “Of all of them, she wasn’t so bad.”

“I cannot believe you stick up for her.”

“She wasn’t cruel. At that court, that was quite remarkable.”

“She’s seventeen. Disgusting! How could he marry her? He and Mother were such lovebirds. Never has there been a couple as devoted as they. If I had a husband like that—”

“You sound like María—the starry-eyed romantic.”

“Like how María

was

. I hear she does not find marriage as magical as she had dreamed. Her husband will have nothing to do with her beyond filling a cradle.”

I thought of my newest infant at home, named for her once starry-eyed aunt. I, too, was but a filler of cradles. “No. Poor María.”

Catalina’s expression grew troubled. “How goes it with your husband?” she asked, watching my face.

“Surely you’ve heard.”

“His ambassador tells us he’s a benign ruler, gentle, kind. A friend to England.”

I laughed in spite of myself. How Philippe’s

grand-mère

had despised the Tudor King. She would have personally held his head in a butt of malmsey if she could have. She had brought up her grandson to hate him equally, though now Philippe, as a prince, was coming to admire the shrewd older man’s political maneuvering. As for Philippe’s being gentle and kind, I had bruises on my forearms where he had grasped me the night before. He had been so excited by his talks with the English King that he expelled his energy by bedding me roughly, against my wishes. But to admit to my miserable marriage was to confess my inability to earn a husband’s love.

“The ambassador is well trained,” I said in answer to her questioning gaze. “Tell me—what is the English King really like?”

“Old Henry? As sharp and cold as a dagger pulled from a snowbank. He won’t let me go home and he won’t let me marry his son Henry.”

“Until he comes of age.”

“No. It’s a matter of the King’s having lost interest in the Spanish alliance, but he suspects I might be too valuable to be let go of just yet. I did not mind being betrothed to young Henry.” She sighed. “But now there’s not even that.”

I smiled. “María did have her influence on you.”

“You would understand if you met him. He’s tall, and handsome, with hair the color of a fox. He is very intelligent—he composes music—and he is exceedingly wise for his age—”

“Which is?”

“Almost fifteen.”

I laughed. “A wise almost fifteen-year-old boy. I remember Juan at that age. ‘Wise’ was hardly a word to describe him. Loud, maybe, impertinent, cocky, vain . . .”

A merry voice came from the doorway. “Who is cocky and vain?”

Philippe entered with a slight man whose gray skin and hair belied the youthful sharpness of his eyes.

“Henry, please excuse the informal meeting. May I introduce you to my dear wife, Juana of Castile?”

The English King cautiously kissed my hand, then seemed surprised when I did not open my mouth and quack. What tales had Philippe told him about me? His campaign to slander and belittle me was astonishing. Yet he achieved his purpose. Because of my alleged incompetence, he had declared himself Mother’s rightful heir before his court at Brussels, and no one had protested on my behalf. There was no one Spanish left to protest. My only hope was that once we arrived in the Spains, the Cortes would see through his lies. He would be my consort and nothing more, no matter what untruths he told.

He kissed my hand. “Are you feeling better, sweet?”

“I was never ill.”

Philippe gave the English King a meaningful look. “You are so brave, darling,” he said to me.

“You must have been, to survive a shipwreck,” said the King. His smile was surprisingly courtly for such a plain little man. “Did you have a moment when you feared you would not make it?”

In my mind’s eye I saw Philippe, drenched and sobbing, on the deck of the ship that was to carry us back to the Spains. A violent storm had struck when we were within eyesight of England’s white cliffs. We watched in horror as the vessel next to us tipped, then was swallowed, sails and all.

Bring my jewels!

I had shouted. I waited for Beatriz to put them on me so that my corpse would be known, and had the captain lash me to the mast to keep me from being swept overboard. Meanwhile Philippe had bawled in terror, flailing his arms so that his men could hardly tie on the buoyant wings they had made for him of ladies’ inflated skirts. Our ship broke up just offshore. We were plunged into the icy water.

Let me live for the children,

I prayed as Philippe thrashed next to me, his wings ballooning. Waves had crashed over our heads.

Let me live for them.

“I think,” I said, “that drowning was a reasonable fear for us all.”

“She still has not recovered,” Philippe said quickly. “She is weary, and needs to return to rest now. She will protest—brave girl that she is, she wants no one to know of her troubles.”

“I’m not weary,” I said.

“See?” Philippe laughed. “Just as I say. Sometimes you are not a good judge of your own fitness, sweet.”

“His care for you is admirable,” said the English King.

“Yes,” I said. “He is Philippe the Good.”

My husband flashed me a look of warning and then turned to the King. “Will you please excuse us?”

The King narrowed his miser’s bright eyes. “I hardly got to speak with her. She doesn’t seem that unwell. But if you insist.” He kissed my hand, then that of my husband.

“Will I see you again?” cried Catalina.

“Of course,” I said. Philippe let me kiss her before he led me away.

We walked down a chill hall, the silence broken only by our footsteps on the stone floor and the rustle of our clothing. Near the entranceway, a youth passed us, surrounded by armored attendants over whom he towered. He looked over his shoulder at me, his fox-red hair falling over his eyes.

Philippe took my arm to hurry me along.

Outside, he pulled me aside as we waited for our horses. “Did you think”—his breath came in furious clouds—“to make friends with the English King?”

“I should think you would want me to. We are in an alliance with the English.”

“We? Who is ‘we’?”

“The Spains.”

“Oh? You are the Spains now?”

I held my tongue. It was best not to provoke him.

“Do you wish to enter in a secret alliance with him, to limit my power?”

“That is silly. Henry Tudor has no influence in the Spains.”

“And neither will I, if you have your way.”

“You will have power, as my husband.”

“No. I shall have more. Your insufferably proud Cortes will beg me to take control when they see how incapable you are. People are already talking. They whisper about the fit you had on the ramparts of La Mota.”

“Fit?”

“How you raged along the ramparts, unwilling to listen to reason and come inside, though it was a frigid night.”

“Do you mean the night I went outside to catch my breath? I had no fit. My mother joined me. We talked.”

“That’s not what they say. They say she begged you to come inside.”

“Who is ‘they’?”

“They say after you gave birth to Fernando, you were weak and given to moods. They fear you have your grandmother’s blood, that insanity runs through generations.”

Realization swept through me in an icy wave. The flesh of my arms and scalp tingled in painful alarm. “It’s you. You started these rumors.”

“Rumors? Even your mother was heard to say that you were lost in love without me.”

I should not have let that lie stand when she said it. But I thought it was only words, and words can never hurt you.

“Oh, yes,” he said, “they are saying all kinds of things. That I had to lock you up because you chased after the Viscountess and cut her long hair. That you threw a brick at me. That you set fire to your clothes.”

“I did none of that.”

“Jealous women are capable of anything.”

“You are mad,” I whispered.

“I can say that you must be locked up for your safety as well as that of others, and nobody will come rescue you.”

“Why do you do this?”

“You know why.”

A boy brought up our horses.

“Thank you, lad,” said Philippe. “Take care of the lady. She’s very fragile at present, and I wouldn’t want anything to happen to her.”

The Spains

Philippe I of Castile

41.

10 July anno Domini 1506

M

y view was of Papa and Philippe, swaying on their richly housed horses, their silk robes draped majestically over the haunches of their steeds. A hot wind sweeping off the Meseta and through the dusty streets of Valladolid stirred the scarlet brocade hangings of the Canopy of State held over their heads. A page walked before them, holding aloft the Sword of State, and before him clopped Philippe’s German guards, whose apparent readiness to trample any stragglers cleared the road for our procession as efficiently as Moses at the Red Sea. I had witnessed such a scene before, riding into Toledo to greet Mother upon my first return to the Spains. I had thought it an innocent and touching expression of camaraderie then, a young husband riding with his wife’s proud papa. I had been pleased to take a secondary position. Now, months after Philippe had started his campaign of lies questioning my fitness to rule, I knew better. Mother had warned me. How many more of her observations would come to haunt me, the damage already done?

Philippe looked this way and that, his perfectly curled hair swishing against the high collar of his satin robe. He was barely able to conceal his grin as men and women alike lowered to their knees as he passed. He clearly relished his role as King, even if it was of the Spaniards, whose restrained ways so perturbed him. He would happily be King of any peoples, be they Indios, Turks, or Cipangese, should they pay him enough deference. I saw now that he craved the enforced deference due him as King as a toddling child craves sweetmeats. He would crush anyone who was a threat to his supply, including his wife. Especially his wife.

How easy it was done. Just call me deranged, provide stories as proof, look solicitous, and then generously offer to take care of the kingdom as full King, not just King Consort, until my mind unclouded. Papa argued that, as my father, he should take care of Castile if I was truly unwell and thus preserve my rights until I healed. But Papa’s appeal fell upon deaf ears. The nobles of the Cortes did not trust him. They feared that if he came into power, he would punish those who denied him a share in Mother’s crowns. Would he? He was just trying to help me. He had his Aragón. Wasn’t that enough?

Philippe snapped his fingers, breaking my reverie. Helmeted heads turned. He pointed to the side of the road, where a solitary man stood among those on their hands and knees.

“Why is he not bowing?” he asked, as querulous as a child being told that he must nap.

I looked closer at the man. His face was obscured by a broad-brimmed hat, though there was something familiar about the way he carried himself, so upright and proud. Papa leaned from his horse to whisper to my husband.

“Make him show respect,” Philippe ordered the German guards who rode next to him. “Or seize him, I don’t care.”

The guards wheeled their horses around to confront the man. They barked at him to kneel, and when he did not, they pushed on his shoulders. He resisted, causing them to redouble their efforts. They knocked off his hat, revealing sleek dark hair drawn into a short queue. His face remained impassive as they tried—and failed—to shove him off his feet.

Philippe gaped at the scuffle as he passed. “The fool is mad. Seize him, if that’s what he wants.”

But when my horse neared, the man lowered himself to his knees. He bowed his head, but not before meeting my eyes with his searching gaze of grayest green.

My heart leaped.

Philippe turned around on his horse. I straightened my face and, with the slightest nod, acknowledged my subject before staring ahead. Philippe narrowed his eyes, then turned again.

My whole inner being sang with joy. If I had only one friend in Valladolid, let it be Diego Colón.

Later that afternoon, in the Palace of Pimentel, where we were to stay while the Cortes were in session to determine if Philippe was legally King, I could not get Diego out of my mind. I was alone, or nearly so. I had not had Beatriz’s company in nearly three months. As soon as we landed in the Spains, she had continued ahead to Salamanca, where she was to present the translation of Aristotle over which she’d labored so hard. As for other ladies, I would not allow the Viscountess of Furnes within my sight, even though Philippe insisted that she remain my first lady-in-waiting in title. Nor could I stomach the other Burgundian ladies he had forced upon me. Which suited them—they were glad enough to be free to flirt with Philippe’s men. Katrien was my only companion, and Philippe made much of this.

You see the extent of my poor wife’s derangement? She fancies that a laundress is her boon companion.

Though Katrien was hardly my boon companion, I was grateful for her presence. We had never recovered our former comfort together—I could not shake the feeling that she was withholding something from me—but at least she was not always scrutinizing the state of my mind. As she mended, scrubbed, or swept, I could think or feel whatever I wanted. And she doted on little Fernando, restored to me upon our return to the Spains, as patiently and tenderly as if he were her own.

And so, that afternoon, as I stood before an arched window opening onto the Plaza de San Pedro while she unpacked my traveling chest, I was left to dream of Diego. Swifts darted in the air, catching insects for the cheeping young that waited in their nests, built in the eaves of the church across the way. Had he thought of me during these past three years? Why should he? A man like him had surely married, had children, and become the affectionate father I knew he would be.

I heard footsteps approaching. I turned, holding my breath.

Papa entered and kissed my hand. “How are you feeling, Juana?”

I exhaled with a sigh. “I am fine, Papa. I have never felt unwell.” I did not muddy the waters by mentioning that I was with child. I was well enough, though I was in the early months of my term, and I wished to keep my pregnancy a secret as long as I could. Katrien knew—a laundress knows everything about her mistress’s person—but no one else. I did not wish to see Philippe preen at the thought of his having impregnated me once more. He would gloat about his potency for getting me with child the night he had forced himself upon me on shipboard, while sailing from England. Forestalling this pleasure was one of the few meager powers I had left over him.

“After little Fernando was born, did you not have spells of—”

“Papa, that was three years ago. Don’t tell me you believe Philippe’s lies. Can you not see for yourself that I am fine?”

He swept his gaze over me with a frown. “Your mother said that about herself, too, until the final weeks of her illness.” He glanced pointedly at Katrien. She laid my hairbrushes on my table, as blank-faced as if she were deaf. “She sent me out to hunt the day of her death. She said that she would be there when I returned. God, I wish I had not gone.”

“You were not there when she died?” I asked gently, knowing that he wasn’t.

“No. Fray Hernando was. Of course.”

I swallowed.

He looked up, wincing. “He always understood her. Her whole life, nearly. They were inseparable. He could make her laugh, or cry, more quickly than anyone. Sometimes I was painfully jealous of him.”

I did not know if he was ready to examine the truth. “He was her priest, Papa.”

“I know. I know.” He tried to smile. “

Lo siento

. Look at me getting weepy here. Valladolid always makes me sentimental. We were married just down the street from here, in the palace of Juan de Vivero.” He joined me at the window. “I came to her dressed as a muleteer,” he said, shaking his head slowly. “She thought I was handsome. My God, I loved her.”

The bells began to ring from the tower of San Pablo. We gazed across the plaza, the air between us thick with Papa’s sorrow. I could smell his peppery scent, so dear to me in my youth. His black hair was mostly gray now; his gown hung from rounded, once broad shoulders. Time had reduced my dashing hero to a small, aging man.

He pulled away from the window. “You probably wonder how I could marry Germaine.”

At my table, Katrien opened my Bible and spread my rosary upon it.

I said nothing.

“I’m lonely, Juana. I have been for a long time. I didn’t think your mother loved me anymore.”

“Of course she loved you, Papa.”

“What a cruel jest it was—the symbol of our union plastered in churches and palaces all over the Spains. My arrows, her yoke.

Tanto monta, monta tanto.

Do you know what a fool it made me feel like to see them, knowing that she thought so little of me?”

“Papa—”

“Germaine, now, she thinks I am a god. Or at least a damn important king. She’s young and easily impressed.” He smiled to himself. “I feel like more of a man than I have for years.”

“I’ve met her.”

“Yes. She told me. She wished to come to see you, but I made her stay in Valencia. The Cortes are still not fond of the idea of our marriage—if I have a son, he is in line to be heir to the crown of Castile.”

I had not thought of this. Surely any child of his would be behind my Charles, and then my Fernando, for the throne. Even my daughters would have precedence. But who ever thought I, middling Juana, would be Mother’s heir to the throne?

He chuckled. “Well, there can be no children without a father to make them. I must return to Germaine soon.”

A footman entered and bowed. “A man is here to see you, Your Majesty.”

I waited, thinking it was for Papa.

The footman rose. “Your Majesty,” he said to me, “the visitor is for you. Don Diego Colón asks for an audience.”

Heat surged into my face. “Colón?”

Papa crossed his arms. “I don’t wish to see the man. He reminds me too much of Isabel. She did dote upon his father. She refused to be disappointed by him, even the time the charlatan was brought back in chains.”

“I will send him away.”

“No need. I am ready for a siesta. The heat is too much for me.”

He left as Diego entered.

I was conscious of my thickening waist, of the imprint of another man upon me. Madness. I was married. It was my duty to carry my husband’s child. Perhaps Diego was now wed, too. I looked for a ring as he kissed my hand. There was none.

“I have heard you are unwell,” he said.

“It is just rumors.”

He searched my eyes as he held on to my hand.

I glanced at Katrien. She closed the traveling chest and left.

“In truth,” I told Diego after she’d gone, “my husband wishes me to look weak so that he can rule.”

He said nothing.

I could not bear his troubled eyes. “How is your father?” I asked.

“I regret to tell you that he died. Just two months ago. That is why I am in this city, to settle his affairs.”

“I did not know. I am so sorry.”

“When he returned from the Indies the fourth time, he made his way posthaste to your mother, but she died before he got there.” He lowered his voice, thick with emotion. “It crushed him. He had no other friend in the Spains. I think he gave up hope.” He paused. “There were no mourners at his funeral.”

“I’m sorry. I would have come if I had been in the Spains.”

He squeezed my hand. “I know.”

“Now it is my business to take up his claims,” he said, releasing me. “From my years at your mother’s court, I have supporters in the Cortes. They are sympathetic to my cause.”

I stroked my hand, still radiating from his touch. “Did you tell them about your sugarcane?”

His eyes warmed. “You remembered.”

“Of course. It is an elegant plan.”

“You are too kind.”

“You deserve to be Governor of the Indies. Indeed, as Queen I will make you that.” I grew enthused. “Now I have a reason for being glad of the crowns. I can make you governor. Viceroy. You shall answer to no one—”

“But you.” His face was full of tender regret. “Dear lady, you are most kind, but I cannot accept your offer. I wish to prove myself. If I am granted any title, it will be because I have earned it.”

He opened his mouth as if to say something else, then seemed to think better of it. He smiled. “Here I am, proud that I might earn the right to be Governor of the Indies. I realize now that it’s nothing compared with being Queen of all the Spains. How foolish you must think me.”

“No,” I said quickly. “I don’t think that. I’m—I’m not even Queen until the Cortes proclaim it. And even then, my husband is anxious to take precedence over me. Your role is the more exciting one. How wonderful to govern distant new lands! What marvelous things grow upon them—brilliantly colored birds, wondrous animals, strange fruits. Whenever I hear of your lands, I think of a painting I once saw at the palace of my friend Hendrik. It was filled with fantastical animals, and fruits as large as men. And the most beautiful birds.”

He laughed with affection. “You do like your birds.”

“I do!” Thank God to discontinue this comparison of our powers. “Have you seen your storks of late?”

“Oh, yes. I look for them every day.” He drew closer, then gazed down upon me. “They remind me of you. They make me remember why I work so hard—to be worthy of you.”

I gathered my pearl, hanging from the ribbon necklace Katrien had made me years before. “I have this to remember you, but I do not need it.” I touched his hand. “I cannot forget you.”

He took my hand and kissed it gently.

Shouts in French came from outside.

I sighed. “Philippe.”

He let go of my hand. I curled it against my breast.

“You must tell me, Señora,” he said quietly, “is he bad to you?”

I looked away.

He gently brought my face forward. “I can see the answer in your eyes. I never thought I could kill a man. I know now that I could.”

“Do not say that.”

“How could he dream of harming such a magnificent woman? He is mad not to cherish you.” Gently, he tucked a stray lock behind my ear. “I do.”

He brought his mouth to mine. Warmth filled me with such force that I moaned aloud.

I pulled away with difficulty. “Please, you must go, quickly. My husband has no qualms about harming anyone. If he saw me with you—”