Reluctant Genius (31 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Guiteau was quickly captured, and Garfield hurriedly driven back to the White House. Panic gripped Washington and rippled out across the country. From Cambridge, Mabel wrote to her mother, who was in Europe, “You can have little idea of the state of intense excitement it has thrown everyone in. Cousin Mary says she never saw anything like it since the shooting of Lincoln.” Physicians congregated at the White House, debating whether (in the days before X-rays) an attempt should be made to remove the bullet. The debate spread to the newspapers, where correspondents named Medicus, Old Practitioner, and Common Sense championed their own remedies to heal the head of state. Meanwhile, at the White House, cold air was pumped up from the basement to the sick room through the hot air registers, and staff tried to keep their stricken leader comfortable with glasses of iced champagne. The humid atmosphere was thick with fear: that week, four White House employees came down with malaria.

Mabel was late in a third pregnancy, and eager to escape the heat and move to a house they had rented on the Maine coast. But when Alec heard the news of the president s predicament, he immediately caught the streetcar into Boston and hurried over to Charles Williams’s workshop. There he started designing a kind of early metal detector that would use an electric current to locate the hidden lead bullet. Sumner Tainter helped him translate his ideas into instruments. Alec’s fame meant that his offer to help was taken very seriously by White House physicians. Within days, according to a Washington newspaper, “Professor Graham Bell and Professor Tainter came here from Boston … for the purpose of making, under supervision of attending surgeons, a series of experiments intending to test the practicability of ascertaining by electrical means the location of the bullet which lies embedded in the President’s body. They were driven at once to the Executive Mansion and are now … in the surgeon’s room.”

For the next few weeks, Alec worked day and night at the Volta Laboratory and in the White House to develop an apparatus that combined elements of two different devices. It consisted of an induction balance, which he had originally developed as a possible way of finding metallic deposits in the ground by means of an electric current, and a telephone receiver, which would signal success by means of sound. A reporter from the

Boston Herald

who visited him at his laboratory described the scene: “In cabinets, on tables, chairs and floor were coils of wire, batteries, instruments and electrical apparatus of every sort. The light from the [gas] jets, burning brilliantly in the center of the room, was reflected from a hundred metallic forms.” There were no screens on the windows, which were open in the sweltering heat, and the continuous whine of mosquitoes was punctuated by the sound of slaps as Alec and Tainter tried to protect themselves. Alec ordered more instruments from Boston and Baltimore, and consulted widely among scientists with similar ideas. The president’s carriage was often seen waiting outside the little Connecticut Avenue building, as the presidents physicians watched Tainter hold a bullet in his mouth, clenched hand, or armpit while Alec held the induction balance and telephone receiver in the vicinity of the bullet and tried to detect a sound. “Last night I located successfully a bullet hidden in a bag filled with cotton-waste,” Alec wrote to Mabel, who was still in Cambridge. “This looks promising.” He and Tainter shot lead bullets into slabs of raw beef from the local butcher, to approximate the conditions in which they had to work.

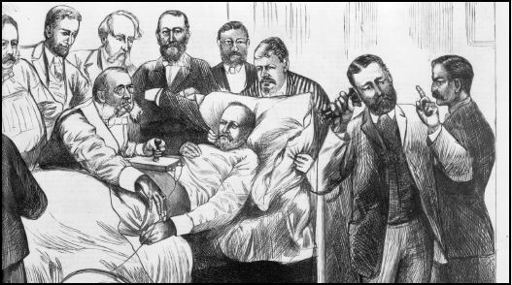

A contemporary engraving of President Garfield’s sickbed shows Alec trying to detect the bullet by sound.

On July 26, Alec and Tainter brought their apparatus into the White House through a private entrance. Alec tiptoed into the sickroom, where Garfield slept, so he might decide how to set up the equipment. He was shocked by the president’s appearance. The once-florid complexion of a man accustomed to open air and good living was now “ashen grey colour,” Alec wrote to Mabel, “which makes one feel for a moment that you are not looking upon a living man.” When the president awoke, Alec and Tainter proceeded with the experiment. There were five physicians plus several White House staff in the room, and Garfield, fearful of electric shock, stiffened at the sight of connecting wires trailing over his body. His weary eyes never left Alec throughout the test. But the results were inconclusive: “a spluttering sort of sound” was all that Alec could catch. So the experiment was concluded and Alec and Tainter returned to the Volta Laboratory. Meanwhile, the wounded president’s condition seemed to improve. He sat up and was able to eat a sandwich and drink a glass of sweet white wine. Prayers for his health, which had been said daily at the Vermont Avenue Christian Church, were suspended.

Mabel missed her husband, and resented the way his efforts were being received. “While he is working the papers are laughing at him and classing him with the crowd of… nostrum inventors.” But Alec was now totally consumed with perfecting his “induction balance bullet detector.” Even his aversion to the Washington heat wave was forgotten, “partly I fancy because he is so busy and excited,” Mabel confided to her mother. Mabel worried that “failure would be so mortifying now,” but Alec was convinced he was on the right track. After five more days and nights spent testing the equipment, Alec was ready to try again. But the second test was also a failure. Instead of the clear localized signals he had detected in the Volta Laboratory experiments, all he could hear was a faint buzzing over a wide area. The following day, he discovered that part of the reason was that the White House staff had ignored his request to remove the steel-spring mattress from the president’s bed. He was furious. “You poor boy,” Mabel consoled him when she heard the news. “How sorry I am for you in your disappointment. I can imagine just how chagrined and mortified you must have felt. … Never mind, courage; from failure comes success, be worthy of your patient and don’t lose heart even if all others are discouraged. I have not the least doubt but that you will eventually succeed. You have never yet failed and will not now. Only I wish I could be with you to help try to cheer you. If it were not for the little ones, I would come right down. I am only impatient to be with you again.”

Oblivious to hints in the newspapers that he was a publicity-seeking crackpot, Alec continued to work alongside Sumner Tainter on apparatus that might detect the bullet. But the president’s life was ebbing away. On September 19, James Garfield died, and his vice-president, Chester A. Arthur from Vermont, was sworn in as the twenty-first president.

The autopsy on Garfield revealed that the bullet, although too deep for Alec’s apparatus to detect, was not the cause of death: it was lodged harmlessly in soft tissue. Garfield’s death was the result of infection introduced by all the physicians who, scornful of theories about the importance of antisepsis, had thrust their fingers into his wound. A few weeks later, Alec demonstrated the apparatus he had used with the president to a group of physicians in New York. Although he himself took little further interest in it, an enterprising doctor called Dr. John H. Girdner put it into commercial production. It was used to help locate bullets in military hospitals behind the lines in the 1894-1895 Sino-Japanese War, the 1899-1902 Boer War, and the First World War. Alec himself was surprised and delighted to hear, in 1886, that the University of Heidelberg had awarded him an honorary doctorate in medicine for his contribution to surgical practice.

Alec was in his study in the Bells’ Rhode Island Avenue home, scribbling a letter to Mabel, when he heard a newsboy shouting news of the president’s death. “Poor Garfield has gone,” he wrote. “After seventy-nine days of suffering to be obliged to give up at last. I hope indeed that there may be an immortality for that brave spirit. … A few days ago we had sermons preached all over the country claiming the favorable turn in the condition of the President,

as a direct answer to the prayers of the nation that were specially offered up the day before

… and now that results have shown that the ministers were mistaken, their belief in the efficacy of prayer will not be shaken in the least.

It will be the will of God.”

Alec was in a grimly philosophical mood as he wrote these words. The president’s death was not his real preoccupation: he and Mabel had suffered their own personal tragedy during the president’s illness. While Alec was sweating over his induction balance, and trying to save Garfield’s life, Mabel had given premature birth to a boy, Edward. “He was a strong and healthy little fellow,” according to Mabel, and “might have pulled through if they could once have established regular breathing.” But the infant lived only a few hours. Edward’s death was a brutal blow to Mabel, who had long nursed hopes for a son who would share his father’s scientific interests and carry the name and fame of the Bells into the next generation.

Neither parent found it easy to accept their son’s death as “the will of God.” Mabel struggled to maintain her health and equanimity, but was pale, thin, and weak for months after the tragedy. Her mother visited her every day; her young daughters often caught her weeping quietly. A year later, when Mabel caught sight of President Garfield’s successor in the casino at Newport, she allowed herself to hint at the reproach she felt toward her husband: “But for Guiteau [the assassin], our own lives might have been different. You might not have gone to Washington, but have stayed with me and all might have been well.”

Edward’s death was no easier for Alec. He kept telling himself that Mabel had been well looked after during her pregnancy, and had he been close during the birth, he probably could not have done anything. But he had to admit that his determination to harness science into the cause of saving the president’s life had taken him away from his family. He was never much good at expressing any feelings other than his devotion to Mabel (the closest he ever got to swearing was a muttered “Shee-sh” through gritted teeth), but he grieved for both his wife and the dead child. He recalled the photo of his deceased brother Edward, taken in his coffin, which his own mother treasured, and in a clumsy gesture of contrition he quietly commissioned a photograph of his own deceased son, and then asked the French artist Timoléon Marie Lobrichon to paint a portrait from it. (There is no evidence that Mabel allowed the painting to be hung.) He also started working round the clock on a mechanical device for administering artificial respiration to patients with breathing difficulties. This “vacuum jacket” was a forerunner of the iron lung: it consisted of an airtight iron cylinder surrounding the patient’s torso, and a suction pump that forced air in and out. But it was never commercially exploited in Alec’s lifetime.

During these months, Alec’s health began to deteriorate. Was it exhaustion? Grief? Guilt? Whatever the cause, he began to suffer the familiar pattern of headaches, sleeplessness, and sciatic pain, and his doctors told him that he had to stop working so obsessively. Mabel forgot her own suffering as she worried about her husband. “Entire rest from mental labor,” she wrote to Eliza Bell, “is necessary to avert serious constitutional trouble.” Nagged by his anxious wife, Alec handed over all his work in the Volta Laboratory to his associates there, who were working on improvements to an Edison invention: a sound-recording device. Alec agreed to take Mabel and their little girls

"wherever in the wide world you want to go.”

Mabel knew exactly where she wanted to go: Europe, where Gardiner Hubbard was busy establishing telephone companies with the help of his other two sons-in-law Both Mabel’s sisters were now expecting babies, and Mabel’s mother had accompanied her husband so she could be with them. In late October, the Bells arrived in Liverpool. They spent the next six months taking in all the fashionable cities of late-nineteenth-century Europe, including Rome, Nice, Paris, and London, often with Hubbard relatives. It was the first of many such Grand Tours that they would take.

Mabel always found motherhood easiest when Alec was with her. Elsie was now three and a half years old, with wide-spaced gray eyes and long brown hair—“a little round fat thing,” in her mother’s eyes, “bright and happy and kind to little baby sister.” Daisy, at one and a half, had inherited her father’s thick dark hair and black eyes, and was “perfectly lovely…far more affectionate than Elsie ever was. She talks a great deal more and has such pretty loving ways.” Mabel had developed techniques to “hear” her babies when they cried; she checked their room regularly, and there was always a nursemaid in the household. A series of small terriers accompanied Mabel throughout her life, and their changes in posture and visible excitements would alert her to the crash of furniture or a ring at the doorbell. “I may not be with the [babies] very much,” she wrote, “but I feel that I can look in on them any moment and be sure they are all right.” Nevertheless, all the insecurities of a new mother were compounded by her deafness. As each child mastered speech, she also became aware of her mother’s disability, and this further undermined Mabel’s confidence as a parent. “I am getting rather anxious about it,” Mabel had confided to her own mother in July 1881. “Elsie says so little to me, and so much more to others. She very evidently sees the difference and points out things to me instead of saying them. I fear she may learn to give her confidence and tell her little stories to others until it will be too late for her to care to come to me with them.” Mabel struggled to follow her daughter’s “childish prattle” but was constantly frustrated: “I see nothing as she talks so indistinctly, hardly moving her lips.”