Reluctant Genius (7 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

At Hartford, Alec began to see the potential of sign language, alongside lip-reading, as a teaching tool. He mentioned to his father, in a letter, that he was learning sign language. Melville was furious, and the next letter that Alec received from Brantford included a scolding. Melville wanted Alec to promote the Visible Speech gospel, and its use in deaf education was, in its inventor’s view, only one of its many applications. He was exasperated that his son was allowing himself to be distracted by sign language. But Visible Speech was not really Alec’s first love. For Alec, “rescuing” the hearing-impaired was an end in itself. The disagreement between father and son created a rift between them—a rift that widened as Alec refused to be cowed. Alec was good at what he was doing, and much as he loved his father, he was not going to be bullied from a distance into abandoning his plans. However, Alec never embraced sign language with the Gallaudets’ fervor; he never accepted the argument that sign language was “natural,” and he continued to insist that most deaf children were better off if they remained in the speaking world.

As a young male teacher, Alec was doubly a rarity in the New England school system. Between 1825 and i860, a quarter of all native-born New England women were schoolteachers for at least a portion of their lives. Few of them, however, had any specialist training with deaf children, and many school boards still preferred to hire male teachers (although their salary was two or three times that of female teachers). So Alec, a male teacher who could teach deaf children, found himself in demand. Offers of employment reached him from all over the eastern seaboard, including the Columbia Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb in Washington. But the offers came too late. The Scots immigrant had decided to settle in Boston and establish himself as a teacher of the deaf there. He had adopted the city’s own view of itself. “Though Washington is the political centre,” he acknowledged to Miss Fuller, “Boston is the intellectual centre of the States.” And he wanted to stay connected to the intellectual center so that he could pursue his scientific interests.

Like Edinburgh, Boston was fueled by an Enlightenment belief in scientific progress and human perfectibility. Between 1810 and 1865, while its population jumped from 30,000 to 140,000, Boston was far ahead of other American cities in social reforms: movements for prison reform, women’s suffrage, and temperance; campaigns against slavery and warfare—all caught fire here. The 1776 American Revolution was launched from Boston, and heated debates within the city’s churches, taverns, and newspaper columns over the abolition of slavery had helped to precipitate the Civil War in 1861.

The Liberator,

published by William Lloyd Garrison out of a hole-in-the-wall office on Washington Street, was one of the elements that had reshaped the antislavery campaign in the northern states into a powerful moral crusade.

Foremost among Bostonian preoccupations was education. The Massachusetts State Board of Education had laid the foundations for the country’s first public school system, with properly trained and paid teachers, books, and decent schoolhouses. On Boylston Street, a beautiful Romanesque Revival building housed the Boston Public Library, founded in 1848 as the first large municipal public library in America. Even the poorest city resident could settle between the marble columns of its reading room to peruse the latest publications. And within a stone’s throw of Alec’s Beacon Hill lodgings were some of the finest academic institutions in the country. America’s oldest university, Harvard, was just across the Charles River in Cambridge, while the Massachusetts Institute of Technology had recently been incorporated (its first building was being constructed near the museum on Boylston Street). The city also claimed leadership in the manufacture of scientific apparatus and in medical science. The first issue of

The New England Journal of Medicine

had been published here in 1812, and Massachusetts General Hospital claimed that its physicians were the first to use ether as an anesthetic during surgery, in 1846. If Alec strolled out of Pemberton Square and into the Public Garden—the best laid-out public garden in the country—he could stop and admire a florid Victorian concoction of granite and red marble: the Ether Monument.

The string of civic achievements had given Bostonians a robust belief that there was a solution to every problem. Accustomed to Scots pessimism and Canadian self-doubt, Alec embraced this confident new attitude. He was excited to see that the city had emerged as the hub of the closely knit telegraph fraternity, thanks to its concentration of mechanical expertise and capital. He realized that, in Boston, he could support himself by teaching, and in his spare time return to the telegraph experiments he had begun years ago in England and had continued to ponder in his parents’ garden in Brantford.

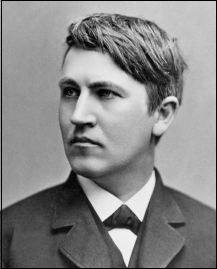

Thomas Edison, a trained telegraph operator, applied for his first patent in 1868 and seemed bound to win the race to invent a multiple-message telegraph.

Of course, there were other eager young inventors with the same goal in mind. One was Michigan-born Thomas Edison, a short, jaunty, hard-of-hearing hustler whom Alec would rival in accomplishment and fame. Edison had recently spent twelve months in Boston before moving on to Newark, New Jersey. Like Alec, he wanted to be the person who discovered how to send several messages at once over a single telegraph wire. Edison appeared more likely to succeed in the quest because he had the technical background that Alec lacked. While Alec was still collecting birds’ eggs in Edinburgh, the cocky Midwestern youth, his exact contemporary, had got his first job as a “Knight of the Key,” or telegraph operator, on the Grand Trunk Line at Stratford, Ontario. He moved rapidly up the telegraph tree, and qualified as a first-class operator while spending evenings and weekends reading Michael Faraday’s

Experimental Researches in Electricity,

and tinkering with telegraph repeaters and sealing wax. Hungry to make his mark on the world, Edison had even rigged up a primitive private-line telegraph system in Boston on which to experiment. With the reckless panache that would characterize his career, he had strung his lines over the roofs of houses next to his customers’ offices without bothering to ask permission from their owners.

Edison was determined to solve the problem of multiple messages by manipulating the electric current. Alec, still preoccupied with Helmholtz’s experiments with vibrating sounds, wanted to explore the idea that the same wire might carry different tones. At the newly built Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Back Bay, there was a complete set of Helmholtz’s acoustic apparatus that he was invited to examine. Perhaps because Helmholtz’s book on sound was in German, Alec’s understanding of his work was flawed: he thought the German scientist had not only created synthetic vowel sounds but also had sent them from one point to another over an electric wire, in the same way that the telegraph worked. It was this misunderstanding that led him to believe that the transmission of the spoken word was possible. He dreamed of transmitting not just electrical impulses but the sound of the human voice. Soon he was tinkering with electromagnets and tuning forks until dawn crept across the sky. Despite his mother’s entreaties, he had again become a night owl, allowing himself only three or four hours of sleep.

Alec’s only source of income, regrettably, remained teaching. After another summer with his parents in Brantford, he returned to Boston in September 1872, intending to build up a practice of private students and to teach at Miss Fuller’s school. He took a second-floor apartment in 35 West Newton Street in the South End. He could afford rooms in the bow-fronted brownstone house because this once-solid residential district was rapidly going downhill, as fashionable Bostonians moved across town to the newly developed Back Bay area. His two-room suite consisted of a parlor and a second room that served as his schoolroom by day and his bedroom by night. (“If you use your school room for a bedroom,” fussed Eliza, “take care it is thoroughly aired.”) He put an advertisement offering speech lessons in the

Boston Transcript

and soon had a dozen students.

One, a five-year-old boy named George Sanders who had been born deaf, moved into another suite in 35 West Newton Street along with his nurse. “Little George progressing splendidly,” Alec wrote home in November. He was a “loving and lovable little fellow…. Expect great results with him if I can have him with me for two or three years.” Eliza reluctantly accepted that she had lost her son to Boston: “You are now, my dear Alec, upon your own legs, and must have all your wits about you.” Keen to show his mother that she still mattered to him, Alec sent her the latest model of a hearing tube. “Well my dear boy the tube arrived safely,” Eliza wrote. “I must use it for company and strangers, it being too powerful for everyday use.”

As soon as the last student of the day left, Alec would eagerly return to his telegraph experiments. He set up a table in his parlor and began to gather the components with which to replicate Helmholtz’s device for producing an electric current of sustained frequency. He made most of his own equipment, and his table had a cover that he could lock to protect his work from competitors’ eyes. Flicking his dark hair out of his eyes, he would crouch over his equipment in the flickering gaslight, laboriously winding copper wire around iron cores to make electromagnets and cursing his own clumsiness. Maybe, he hoped, a telegraph breakthrough would make him some money, but he couldn’t afford to apply for a patent, so he had to operate in total secrecy.

The pressure of teaching by day and experimentation by night soon triggered the return of his headaches. Back in Canada, his parents fretted about their weak-chested son’s susceptibility to the kinds of infections and sicknesses that were as common in Boston’s overcrowded tenements and smoky back streets as they had been in Edinburgh. Melville, still irritated that Alec was straying from the Visible Speech campaign, huffed and puffed. “I value your health above all things,” he said, adding, “I prescribe a steamboat trip on the upper lakes.” In June, Alec returned to Canada and did as his father suggested. He spent July on a steamer, traveling through Georgian Bay to Lake Superior, then back through Lake Huron. He stopped coughing and his head cleared.

Alec’s third winter in Boston was easier than the previous one. The most important change was his appointment as professor of “Vocal Physiology and Elocution” at the newly established School of Oratory in Boston University. The university had begun in 1839 as the Newbury Biblical Institute in Vermont but had moved to Boston and now boasted several new faculties, including schools of law, music, and oratory. Isaac Rich, a successful fish merchant, had bequeathed it his $1.5 million estate. (The university’s directors wisely decided not to name the university after its benefactor; after all, who would donate funds to “Rich University”?) A significant part of the new university was housed at numbers 18 and 20 Beacon Street, including the College of Liberal Arts, the School of All Sciences, and the School of Oratory, as well as a room used for daily chapel meetings. Alec was given an office at 18 Beacon Street, where he could receive his private pupils, and was paid five dollars an hour for his university lectures.

For a twenty-six-year-old without a university degree, a professorship was a tremendous boost to both ego and credibility. He couldn’t help grinning enthusiastically at the young men and the sprinkling of young women (the university was among the first to admit women) who clattered up and down the steep, narrow staircase outside his second-floor office. It is easy to imagine that Melville Bell’s pride in his son’s progress was diluted by a spurt of envy: a steady appointment at a prestigious university was exactly the kind of position he thought

he

should hold. He was soon nagging Alec about allowing university duties to distract him from the important job of promoting Visible Speech. When was Alec going to get a promotional pamphlet for the VS system printed, and start talking it up?

That

was the way to make some money. Alec assured Melville that his university duties would occupy only about five hours a week. His timetable consisted of lectures at the university on Mondays and practical classes on Wednesdays. Within days of his arrival, he had twenty students in his university class, and several private pupils to teach on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays.

Then George Sanders’s grandmother offered Alec free board and lodging in her home in Salem, an eighteen-mile train ride from Boston, in exchange for continuing George’s education. George adored the teacher who, the previous year, had taught him the rudiments of lip-reading and articulation. Now Alec gave the six-year-old his morning assignments before he caught the train into Boston. In the evenings, as Alec walked back from Salem station toward the Sanderses’ clapboard mansion on Essex Street, Georgie would wait at the parlor window, in his smart little suit and with his hair neatly combed. As soon as the child saw his teacher, his gray eyes would light up. After a little more instruction, George would go to bed and Alec would turn his attention to his experiments. One day George took an illicit peek into his tutor’s bedroom. “I found the floor, the chairs, the table, and even the dresser covered with wires, batteries, coils, cigar boxes, and an indescribable mass of miscellaneous equipment,” he would recall fifty years later. “The overflow was already in the basement, and it wasn’t many months before he had expanded into the carriage house.” Mrs. Sanders turned a blind eye to the mess—her grandson’s progress was too impressive to allow a tangle of wires or Alec’s nocturnal work habits to disrupt the relationship. (She did worry about the young Scotsman’s lack of sleep, however, so she got into the habit of cutting a few inches off each of his candles, forcing him to go to bed earlier.) By December, George could read. By spring, Alec had developed a way that they could spell out words and communicate easily in both public and private.