Restitution (12 page)

But the pieces were falling into place, one by one. Once again, Marie cast out her net and pulled in contacts. She discovered that in the town of Zlin there was a Gestapo official who, like George Harwood, was known to take bribes. This was all she needed to know. She awoke early one morning and announced to her children that she would be traveling by train to Zlin, staying there overnight, and would return later the next day.

“I haven't even told your father these details,” she said, before leaving the villa. “Better not to worry him too much more.” Though Victor had remained in Paris as per his wife's wishes, the stress of being separated from his family was taking its toll. Marie knew this from their telephone conversations and she in turn worried about her husband's health. “I'll give him the good news tomorrow, after I've got the papers in my hand,” she said brightly.

Karl wondered if her optimistic attitude was merely a front for the anxiety that she surely must have been feeling. He too was anxious for his mother's safety, though he could not state these concerns. He watched her, wondering how she was ever going to pull off this feat. What Gestapo official would agree to meet with a Jew, let alone a woman? But Karl knew that his mother had already proved herself capable of accomplishing the impossible, and Karl prayed that this journey to Zlin would be no exception. When he saw her striding confidently up the sidewalk toward their apartment the following evening, he knew that she had accomplished her mission.

“I've got them,” she announced jubilantly as she entered the villa and grabbed her children in a fierce embrace. “Imagine! It only took a few minutes.” She went on to describe the trip. The train ride to Zlin had been the most anxiety-provoking part of the journey. In every car, Nazis patrolled the aisles or mingled with passengers. Marie's greatest fear had been that she might be asked for her papers and questioned. It would have been difficult, under Nazi scrutiny, to hide her religion. But the trip passed uneventfully. Perhaps the guards had passed her by because she looked so refined. Several actually had nodded at her and she had forced herself to paste a smile on her face as she hid her trembling hands in her lap. In Zlin, she proceeded to Gestapo headquarters, and asked to speak to the official whose name she had obtained. He saw her immediately.

“Like being close to the devil himself,” Marie described. “That's what it felt like in the room with that man staring at me.” She breathed in deeply before continuing. “I took the envelope of cash from my purse and slid it across the table toward him. He would never have taken it from my hand â wouldn't dare touch me, a Jewess. But my money was certainly good enough for him. We barely spoke, we didn't need to. He knew why I was there. Look Karl, Hana, my hands are shaking even now as I think about it.”

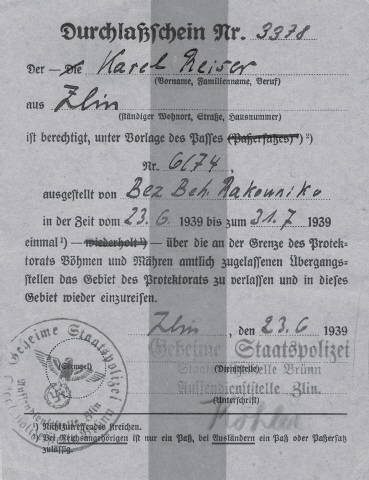

Karl could only imagine what it must have been like for his mother to face this Gestapo officer and ask for the exit papers. Her initiative and sheer guts were more impressive than ever. In exchange for payment, Marie had left the building with the exit permits in hand. Proudly, she displayed the documents to her children, one in her name and one in Karl's name. Hana would travel under her mother's passport. Everything was now in place, but Marie was still worried.

“What if these permits are invalid?” She voiced her apprehension that evening as they celebrated the acquisition of the documents. All the necessary papers lay on the table in front of them: passports, exit permits, even the false baptism papers and Catholic marriage certificate. This accumulation of documentation had more value to the family than their entire estate. And Karl knew that they were luckier than most to have collected them. There was the underlying sense of a near stampede in Prague as other Jewish families were desperately trying to acquire the very papers that the Reisers had lying in front of them. “What if the exit documents are forgeries, or stolen from someone else?” Marie continued. “What if that Gestapo official deceived me, just as that terrible lawyer did? Without proper papers, we could be stopped at the border and that would be that.”

Chances were, with invalid papers, not only would they be turned back from the border, they would be arrested. Though sanctions against Jews had been slower to take effect in Prague, this infraction would no doubt lead to severe consequences.

“I do have one idea,” Marie said, turning to Karl. “But you are going to have to agree to this.”

What now

? Karl wondered.

“I want you to test these documents for us.” It seemed that Marie had already thought this plan through. “I want you to get on a train to Paris with your permit. If you can get through passport control at the border, then we will know that the papers are good.” Once safely in France and reunited with his father, Karl would notify his mother and sister to come immediately.

The plan hung in the air as Karl digested its implications. “You're smart and quick, Karl,” Marie added, reaching across the table to take her son's arm, as if to pass her strength to him. “You can manage any situation. I'm sure of that.”

Karl swallowed and nodded. This had an ominous tone to it. But he knew what he had to do. He was being asked to put himself on the line, to test these waters for the family. And, in the absence of his father, he was the only one who could do it.

Karl's exit permit issued by the Gestapo in Zlin, June 23, 1939.

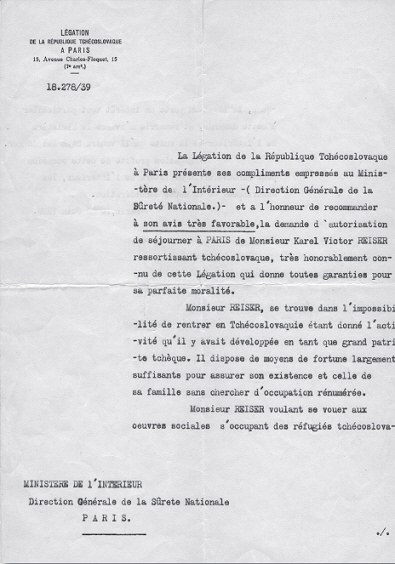

A two-page document issued by the Czech Embassy in Paris.

This document enabled Victor to remain in Paris while trying to get his family out of Czechoslovakia. It provided support to him in his efforts to obtain his “carte d'identité,” the official papers needed to remain in France during the war.

Prague, July 18, 1939

THE WILSON TRAIN STATION was bustling in the twilight of a warm Prague evening. No one paid too much attention to the attractive woman and her tall, pale son who stood together on the platform waiting for the departure of the PragueâParis express. It was an overnight train, due to arrive in Paris early on the morning of July 19. Nazi officials patrolled the station, glancing casually at the passengers who were waiting to depart or awaiting the arrival of friends and loved ones. An uneasy calm prevailed as people went about their business and tried to avoid catching the eye of the guards. Karl and his mother were doing the same.

“I'm so proud of you, Karl,” his mother whispered, reaching up to kiss her son on the cheek. When had he grown to be so much taller than she?

Karl returned her embrace, feeling the weight of responsibility on his shoulders for what he was about to do. His mind was galloping, reliving all that had transpired in the preceding twenty-four hours.

Packing had been simple. No one wanted to attract too much attention and a large quantity of luggage could draw unwanted questions from border officials, or those Nazi guards who continued to walk past on the platform. He had only brought clothing and a few books with him from RakovnÃk to Prague, and he would take the same belongings, plus his precious camera, to Paris. Perhaps he would have a chance to use the camera again once the family was in a place of safety. Karl's small brown suitcase rested next to him as he stood with his mother.

Saying good-bye to Leila that morning had been difficult. The truth was, if this escape were successful, it was possible that he might never see his nanny again. She had held on to Karl for a long time, sobbing quietly, and wishing him a safe journey and a good life. The memories of his childhood in her care welled up inside of Karl even now and he shook his head trying to regain his composure. Bidding farewell to his dog was also painful. He knew in his heart that it was unlikely he would ever see his pet again, and when he had buried his head in Lord's neck and clung to him, the Great Dane squirmed and barked loudly, perhaps sensing that something was different in this embrace with his master.

Just before leaving the villa, Karl had had one last, brief conversation with Hana. “Do you still think this is all an adventure?” he asked.

Hana had tilted her head to one side and eyed her brother thoughtfully. “We will all be together looking back on this one day, Karl. I'm sure of it. Besides, you're the one who always gets me out of trouble. So I'm counting on you to do that for all of us, now.”

Karl recalled all that and more as he stood with his mother waiting to board the train. “I hope it's on time,” he said, trying to make casual conversation.

“I'll see you in Paris in a few days,” his mother replied, reaching up to straighten his starched shirt collar.

Karl nodded. His mother's words sounded calm and confident, but he knew her well enough to detect the worry in her eyes. This could not have been easy for Marie â to relinquish her son with no certainty that he would be safe. As for Karl, in truth he was feeling a bit like the sacrificial slave about to be thrown into the gladiator's ring. He was hopeful that all the papers were legitimate, as the Gestapo official had promised, and that he would make it safely across the border. But they were putting their lives into the hands of a Nazi, all of whom were deceitful as far as Karl was concerned.

The fear that things might go horribly wrong crept into his brain and threatened to destroy his resolve. What if he were detained at the border and questioned? He had rehearsed the statement:

I'm traveling to Paris to meet my father.

It sounded innocent enough. But everyone knew that instead of regular border guards, the border was now policed by the dreaded SS in their black uniforms with the swastikas on their armbands and the skull-and-crossbones emblems on their caps. That image alone terrified Karl. He wondered if he had it in him to be as resourceful as his father, who was working furiously to bring the family together, or as his mother, who had already saved them several times over. Yes, his mother had been more of a hero than he ever could have imagined. Could he follow in her courageous footsteps? He shook his head. He simply could not let his mind dwell on the danger. He had to hold on to the belief that he would be in Paris in several hours and happily reunited with his father.

A train attendant passed by on the platform and Marie stepped out to stop him. “Excuse me,” she said. “My son has a ticket to Paris on the express train.” As she spoke she reached into her handbag, withdrawing a sizeable amount of money. She rolled the bills into a tight wad and pushed them firmly into the attendant's hand. “You'll see to it that he is not disturbed and that he has a safe and comfortable journey, won't you?”

The steward looked down at the cash in his hand and then up into the steady gaze of the well-dressed woman in front of him. He glanced at Karl and then again at his own hand. Karl wondered if he suspected that they were Jewish or merely wealthy travelers. Finally, the attendant tipped his hat, bowed slightly, pocketed the money, and smiled at Marie. “Madame, if you would give me the young man's papers, I'll see to it that he isn't bothered the entire journey.”

Marie reached into her bag once more and withdrew Karl's travel documents: his ticket, passport, and the all-important exit permit needed to get out of Czechoslovakia and safely into France. These would have to be presented at the border. She hesitated a moment, and then handed them over to the waiting steward. He accepted the documents, tipped his hat once more, and signaled Karl to follow him.

There was only time for one more quick good-bye. “I'll give your love to Father,” Karl said urgently as he embraced his mother once more. “And I will see you in a few days.” Then, he picked up his suitcase and, with one last backward glance, he marched quickly after the attendant and jumped easily onto the train.

The attendant led Karl down the aisle of sleeping compartments and entered one at the end of the train car. As soon as Karl was inside the coach, the attendant pulled the curtain around the compartment. Before leaving, he turned to Karl. “I'll do my best to ensure that your trip is uneventful, sir.” With that, the steward exited the car, and Karl was alone.