Return (6 page)

Authors: Peter S. Beagle; Maurizio Manzieri

Tags: #Fantasy, #Fiction, #General, #Science Fiction, #Women

“

The moon is the moon.”

I came back to that more often than I revisited anything else that Master Caldrea had told me. In my experience—and even then, I had more of it than I liked—anything involving the moon usually takes place at its fullest, or when it stands at zero, vanished altogether for two or three days. Immured in this windowless cell, I had no way of knowing the phases of the moon, or day from night. But when I felt strong enough I knew in all my battered bones that it was time for me to go. Now. That moment. Literally.

And I knew a way to do it, a way that I had always known. A way that I had never wanted to take, and never had, and did not want to take now. But there was no choice.

The man who laughs

taught it to me. Separately he had taken both of us in, Lal and me, many years before we finally met, and he taught us each exactly what we needed to know, even though neither of us could have imagined it at the time. In Lal’s case he gave her an emerald ring to ease the nightmares born of a slave’s childhood, and a little gardener’s charm as well, one that would raise the dead as easily as a cabbage. He also introduced her to the deep sea, which claimed her heart the moment she set foot on a battered, pitching old fishing boat. She will die there, at sea, like enough, though not while I can prevent it. Even as much as I hate boats.

For myself, he gave me the woman-shape, which made absolutely no sense to me at the time, but which had more than once preserved the strange life

he

knew was marked out for me. There was another gift too—one that came at a cost. They all do, really, but most often you don’t know it until the gift has been employed and the price is at your door. With this one I knew the price well in advance.

At first I was not even sure I recalled its workings. I did know that it involved certain incantations and certain…other spells, if you will, which would have been difficult to conceal in the limited privacy of my previous cell. Here, alone in the dark, I managed surprisingly well, saying the right words at the right moment and feeling my way through the few other things you have to do, just as

the man who laughs

had shown me, over and over, so very long ago. I was quite proud of myself, and liked to think that he would have been, too.

But how do you tell, in utter darkness, whether or not you have become invisible?

You go on bumping into things, of course, and you can’t see your hand before your face any more than you ever could. I had no idea whether or not the charm had succeeded until I stepped out of my unlocked door and approached the guard, who was still yawning in my face and scratching his belly when I laid him gently down to sleep. It is quite a tidy and efficient spell, really.

It also endures no more then a quarter of an hour; seventeen minutes at the outside. Seventeen minutes, paid for with at least three years off your life span, or as many, possibly, as five. But years there will be, and I could only hope that I was sacrificing time during which I’d just as soon have been dead anyway.

The man who laughs

told me that he himself had used it more than once; but then, of course, he was a wizard. Wizards live a very long time.

The moon was only a pale gray fingernail above me as I limped through the great doors. It seemed to be flickering feebly, like a candle about to fail. There was no turmoil, no noise of discovery and pursuit; none of my poor guards must have wakened yet. But they would, so I made off toward the marshes, exactly as I had done before, determined to be well away before the spell wore off or any alarm was raised. Being no longer the young man who plunged blindly and wildly down a weed-slick slope—cracking his head open on a rock, almost ending his flight right there—I circled cautiously, watching where I put my feet, and went to ground no more than half a mile from

that place

. By then I was solidly visible again. Finding dry leaves under a shroud of damp ones, as the fox had taught me, I put moons and Hunters out of my mind, and caught what sleep I could.

If they had had dogs…but of course they never did, completely reliant on the Hunters as they were. I woke to voices carried on the wind, too distant to be intelligible, and with no indication that they were drawing closer. I washed and drank at the nearest stream, numbed my hunger with

tilgit,

which grows wild throughout the marshes; and examined the sky, satisfying myself that the following night would show no moon at all. That would be my night. The Hunters might or might not be waiting for me, but I was coming for the Hunters. And the Tree.

Madness? Bravado? Both, and neither…and all that I had become since that first Hunter made a professional killer out of me. Yes, it was a killing that sent me flying to the shelter of

that place

as a child, the murder of the man who had so injured my sister—but it was killing the Hunter, seeing those contemptuous eyes widening with the shocked understanding that his pitiful, helpless victim, armed with nothing but the broken haft of a paring knife, had struck him down, had ended him, that truly changed me…it is not a good thing to feel that powerful. It is

not.

I would unlearn it, if I could.

Between now and tomorrow’s absent moon, I had plans to make and a day to use wisely. The morning was annoyingly bright and clear, but I moved with the sun, taking advantage of every shadow and every fragment of shade as I eased closer to

that place.

I could make out figures and faces coming and going; compared to its normal somnolent air, the mansion was humming like a nest of those little black

miriki

bees that do not die when they sting you. I recognized two or three guards, and even the boy who had told me how dishes were returned to the kitchen. But I saw no sign of Master Caldrea, which concerned me a good deal.

Indeed, it concerned me enough that I risked recapture more than once, hoping even to spy him through a window. I knew better than to assume that he had given up on my recapture, nor to imagine that

he

imagined that I could choose escape over revenge. I slipped back into cool shadow on my belly, and thought hard about Hunters.

Once you have observed Hunters at close range—and presumably survived the encounter—you can never mistake them again. But I had spied none since my arrival, except for the one who had tortured me, and surely they would have been alerted since my escape. As a boy, I had seen them on rare occasions: small to medium in height, lithely built, with light eyes, pale brown skin, and distinctively quick, agile movements. They had nothing I could ever discover to do with the actual workings of

that place:

we youngest servants generally thought they were a special kind of monk, while the older boys hinted darkly at their real function, and dared us to approach and speak to one. I certainly never did, and I never knew anyone who took up the challenge. The Hunters look like what they are.

But I had seen none during the time I was held captive in the guest wing—nor during any of my escape attempts, either, when one might think Hunters would have been much in evidence. I spent much of that last day roaming the entire area, always returning to

that place,

chancy as it was, wondering where they were and still hoping for a sight of Master Caldrea.

I finally got my wish late in the afternoon, when he came briskly through the double door, walked into the open, then halted midway to the bushes and to shout this speech to the air. “My dear Soukyan, if you are within the sound of my voice, as I would think you are, may I first heartily praise your determination and your ingenuity—and may I also assure you that these admirable qualities will make no least difference to the outcome of this night. Savor your remaining hours here, since I do not for a moment imagine you will be wise enough to employ them in running for your life. Which would not help, either; if I wished to call them off now, they would pay no slightest heed to me. Take it as a compliment, Soukyan, and do enjoy this beautiful evening. The night will be less so.”

He bowed formally, as he had done so often upon leaving my cell, and went back into the mansion. I lay still for some time.

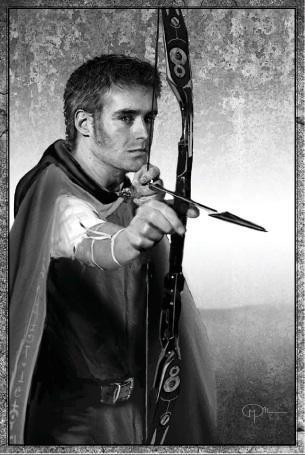

I did take advantage of the twilight’s sweet-smelling warmth by slipping back into the woods to tend to dinner. Without my bow or the

trimoira

dagger, I was not only defenseless, but faced nourishing myself on

tilgit

for what might well be my last meal. That thought being completely intolerable, I fashioned a snare from a V-shaped branch and a few supple twigs, caught a plump

starik

, and devoured it raw.

Death had been much on my mind all that day, in the most practical sense. Giving Master Caldrea proper credit for intelligence, and for having known me in my childhood, I assumed that he would expect me to attempt to recover my weapons, and would have them all under heavy guard, inaccessible, as I would have done in his place. But I could not even find out where they were being kept, no matter whom I followed, no matter how many risks I took to spy on hurrying monks and tantalizing clumps of sentries. Barring a stout tree-limb trimmed into some sort of bludgeon, I was shortly about to face empty-handed an unknown number of the most gifted and pitiless killers I had ever encountered. Utterly absurd frustration at one end of the day, suicide at the other: Soukyan to the life, Lal would have said.

At one point I even crawled as close as I dared to the stable, thinking that the weapons might have been hidden in the hayloft, but heard only my own mare, who nickered when she sensed me near. Any guards who knew horses, Hunters or no, would have been out and swarming on the instant, so I discounted the stable and moved on.

Somewhere around that time, with dark coming on, I realized that I was beginning to look seriously at promising branches.

Dusk is a bad time for me—always, since I was very young, long before I became whatever exactly I am. I have never known why that should be, and it still irritates me. A mercenary may grow wistful, even sentimental, regretting losses and mistakes, stupidities and misjudgments and crimes that cannot easily be remembered as mistakes…but what kind of regrets can a small boy possibly have who begins to cry as the sky turns slowly violet and the first twinge of cold comes into the air? I have no more fear of midnight than Lal-after-dark does, and the deep hours before dawn have often been my own high noon. But twilight can be hard, and right then I was desperate enough to determine on a completely insane gamble in order to acquire at least

some

weapon. I focused on one guard, younger than the others, who seemed not to be guarding anything in particular, but rather strutting here and there, striking poses with his long broadsword. As he wandered increasingly close to the shadow where I lay, I prepared to pounce, catch him by the neck, strangle him silent, and drag him into the woods to finish him. I am good at this. If I were not, I would have been long dead myself.

But with that boast on record, let me report further that as I crouched, behind me a wheezing old voice rasped quietly, “Stir an inch and die, traitor Soukyan!”

Brother Laska

.

I turned my head and saw him there, twenty feet behind me, grinning his splintery brown grin and holding my bow by the end, like a spear. I had heard nothing of the old gatekeeper’s approach; as my nerves were astretch to their greatest possible extent, this implied more skill on his part than I knew. Nevertheless he did nothing when I took the bow away from him, but only muttered, “I have the arrows. Come for them two hours after sunset, when the Masters have gone.” He turned away, standing straighter and walking more firmly than I ever remembered seeing him. Over his shoulder, he added, “Then I will take you to the Tree.”

And so I hid once more, and waited. Brother Laska did not lie: after sunset the Masters did leave, one by one, through the great doors, apparently in order of rank, for Master Caldrea was the last.

When it was true moonless dark, dark enough for me to hope I might be taken for a guard if I were seen—though none of those carried bows—I stole toward the great door, meeting no one on the way, and slipped inside for what I knew would be the last time. Brother Laska was waiting for me at the closet under the stair, my dagger, my pack, my arrows and the quiver in his trembling hands. I took them with gratitude—he even had my flint and steel as well—asking, “Have they been here all the time? Since Master Caldrea took them?”

Brother Laska shook his yellow-white head, grinning again. “He hid them, but I found them. I find everything.” He watched as I tested and adjusted the new string and sighted along several arrows, to make sure that no dampness had warped them. He said, “I knew you would come for them.”

“My weapons?”

“The Hunters.” I heard footsteps and ducked into the closet, shielding my face, as a pair of apprentices passed, teasing Brother Laska and chattering about the shapeshifter who could be a man or a woman, and make himself disappear altogether, when he chose. Brother Laska growled them along, and I asked him bluntly, “Why are you helping me? What game are

you

playing?”